Several bumblebee species are very active at this time of year, collecting food for the next generation or busy mating. BTO’s Rob Jaques writes about watching, recording, and supporting these charming insects.

Why should birders record bumblebees?

Many birders switch to watching and recording invertebrates during high summer, when birds are at their quietest and autumn migration is yet to really begin. Butterflies and dragonflies are the natural first port of call for most, as these large, charismatic insects are easy to see and there are plenty of resources available for identifying them.

Bumblebees are also large and colourful, but they have a reputation for being difficult to identify. While they have their challenges, with some practice and care they are certainly no more difficult than a distant sandpiper or a Phylloscopus warbler – like a Willow Warbler or a Chiffchaff – in a densely-leaved tree.

Bumblebees are a rewarding group of insects to watch, thanks to their interesting life history which involves queens, female workers and males, and quite often, their parasites. We can draw them into our gardens easily with a few of their favourite plants, and it’s worth remembering that bees are an important food source for many familiar birds. Great Tits, for example, are particularly adept at catching bumblebees!

Most importantly, however, you can monitor bumblebees in Garden BirdWatch. This gives us the means to follow their fortunes, better understand how they use our gardens and learn how to provide for them in a changing climate.

Losses and gains

There are currently 24 bumblebee species which breed in the UK. Some of these are incredibly widespread and easy to find, while others are restricted to particular habitats.

Some of these rarer species used to be more widespread, but due to habitat loss and other unknown factors their populations and ranges have contracted and they are now only found in isolated pockets. Sadly, a number of species have become extinct in the UK, including Cullum’s Bumblebee and Short-haired Bumblebee.

Results from the Bumblebee Conservation Trust’s BeeWalk scheme show that the numbers of our more common bumblebees have also begun to decline.

Despite these notable losses, some species are doing well. Common Carder Bees have shown increases in recent years, and in 2001 a bumblebee new to the UK was found in Wiltshire, likely having made its way across from mainland Europe. This species, the Tree Bumblebee, has spread dramatically in the UK in the past two decades, exploiting a niche (nesting in tree cavities) that is rarely used by other UK bumblebee species.

Garden records

BTO’s survey Garden BirdWatch has been accepting bumblebee records since 2008, so we are able to see which species most frequently make use of our gardens.

Our most commonly recorded species in gardens is the Buff-tailed Bumblebee, with 21.5% of Garden BirdWatchers reporting this large and adaptable species. It is typically one of the first species seen each year – the large queens are cold tolerant, and they can often be seen feeding on crocuses, snowdrops and mahonia flowers on sunny winter days.

Buff-tailed Bumblebees are just one of seven common species that we might expect to find in gardens throughout the UK. However, if you are fortunate enough to have a garden on moorland or next to the coast you might find one of our rarer species, such as Bilberry Bumblebee or Moss Carder Bee.

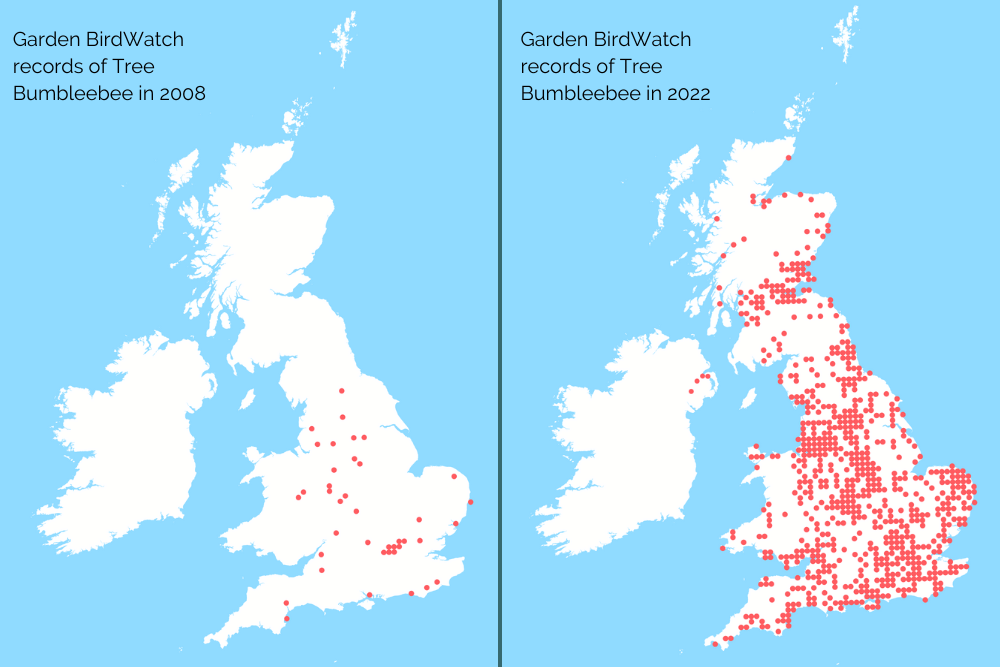

With enough records, we can also use Garden BirdWatch data to see how populations have changed over time. For example, the dramatic expansion of the UK Tree Bumblebee population is clear in the increasing number and spread of records submitted to Garden BirdWatch from 2008–22.

Tips for a bee-friendly garden

- Fill the garden, some pots or even a windowbox with plants such as lavenders, Salvia and Cosmos.

- If you have a lawn, allow it to grow long for more bee-friendly ‘weeds’.

- Avoid using pesticides.

- If you have space, provide winter flowers like Mahonia for bees which emerge early in the year.

Encouraging bees

Fortunately, it is relatively easy to provide for bumblebees in our gardens. They simply need a space to nest, with most preferring to use long grass or abandoned small mammal tunnels, and a steady supply of flowers for nectar and pollen. Leaving areas of lawns and borders to grow long can help provide both, depending on which plants are present.

If you are struggling for consistent wildflowers to feed your local bumblebees, you could try planting herbs, such as mints, lavenders and Rosemary. These are long-flowering and popular with a range of bees.

It’s also worth keeping an eye out for bees in your neighbours’ gardens, to see which plants are most popular with pollinators. You can use this information to guide your own choices.

Identification tips

When we start to identify bumblebees, the first thing to consider is what ‘caste’ the bee we are looking at might be. Most species have queens and worker bees, which are both female, and male bees. The three castes can share similar colour patterns or be quite different from one another. For example, Tree Bumblebee castes all have a gingery-red thorax and a white tip to the tail. This is unlike the Red-tailed Bumblebee, whose queens and workers are entirely black with a red tail, with the males sporting a number of bright yellow stripes instead.

Male bumblebees share some common features across all species: longer antennae, a more squared end to the abdomen and a lack of pollen baskets (the yellowish part of a worker bee’s two hind legs, where the bee places pollen so it can be carried back to the nest). If we can identify the bee as a male, it will help us to identify the species.

At this time of year, the cuckoo bumblebees are particularly numerous. Of our 24 bumblebee species, five are brood parasites of the other bumblebees, using a suite of tactics to lay their eggs in the nest of a typical bumblebee, with the original occupants unwittingly raising the interloper’s offspring.

When searching for cuckoo bumblebees, lookout for long-bodied individuals which seem more sparsely haired, and often with different colour patterns to their host species. They also won’t gather pollen in their reduced pollen baskets, as they don’t need to feed their young.

What next?

If you are new to the exciting world of bumblebees then this overview might not be enough to get you feeling confident. Fortunately, you don’t need to know how to identify pollinators to a particular species to contribute valuable records! The Pollinator Monitoring Scheme runs Flower–Insect Timed (FIT) counts, which only require you to spend 10 minutes watching a small patch of flowers to see which species groups come to feed – for example, bumblebees, butterflies or small flies. This allows the organisers to monitor bee and pollinator populations from year to year.

At BTO, we also have resources available to help you develop your skills. We are now running training sessions on identifying garden bumblebees, which we announce through our weekly Garden BirdWatch enewsletter. Joining Garden BirdWatch is completely free, and you can sign up for the enewsletter for the latest news, seasonal features on garden wildlife, and training courses.

Join GBW for free

Become more connected to nature, learn about your garden wildlife and contribute to important scientific research by joining our community of Garden BirdWatchers.