Read reviews of the books we hold in the Chris Mead Library, written by our in-house experts. A selection of book reviews also features in our members’ magazine, BTO News.

Featured review

All the Birds of the World

Lynx have had a long-term project to produce an exhaustive guide to the birds of the world. It started out with the 17 volumes of the Handbook of the Birds of the World (1992–2013) which has family and species accounts for all birds. This was followed by the two volumes of the Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World (2014–2016). They have now published the third and final stage of this avian odyssey with this current book.

Search settings

Flight Identification of European Passerines and Other Selected Landbirds: an Illustrated and Photographic Guide

Author: Tomasz Cofta, photographs by Michal Skakuj

Publisher: Princeton University Press, Princeton & Oxford

Published: 2021

Vis-migging, the art of watching, identifying and recording all of the birds seen flying through and over a particular watchpoint is better known as recording visible migration. The ability to accurately identify what often amount to little more than smallish dots is something that can only be gained by spending time vis-migging – lots and lots of time, learning the different flight patterns of the different families and the individual species. There is a short-cut to gaining the huge amount of knowledge and experience needed and that is to learn from someone else who has that knowledge and experience. In this book Tomasz aims to do just that, provide the reader with a mentor and a useable toolkit to help begin to tease apart the intricacies of the flight patterns of 237 European and Turkish birds. Each species is assigned an F-wave category (the undulating flight pattern of a bird), ranging from none - no discernible F-wave – to very distinctive, high F-wave, as seen in woodpeckers. Where it is a useful feature, the flight calls are also described phonetically and accompanied by a spectrogram of each call. At the front of the book there is a QR code that links to recordings of the flight calls described for each species, which alone is a very useful resource. Each of the species is illustrated by the most beautiful, original artwork by the author and accompanied by several photographs showing the features that are most encountered in flight. The artwork is sublime and shows each species in great detail from above, below and in profile. Each species is also accompanied by several in flight photographs and though I am not too sure how useful these are, they do provide another point of reference. Would I buy this book? Absolutely, it is a book I wouldn’t want to be without and I have found myself reading through it again and again, sometimes just to enjoy the wonderful illustrations.

All the Birds of the World

Author: Josep del Hoyo (editor)

Publisher: Lynx Edicions, Barcelona

Published: 2020

Lynx have had a long-term project to produce an exhaustive guide to the birds of the world. It started out with the 17 volumes of the Handbook of the Birds of the World (1992–2013) which has family and species accounts for all birds. This was followed by the two volumes of the Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World (2014–2016). They have now published the third and final stage of this avian odyssey with this current book. The publishers state that the book’s aim is “to bring the extraordinary richness and diversity of the world’s avifauna closer to a wider audience.” They do not see it as just an extension to the earlier works but believe they can give access to more people by concentrating on illustrations and range maps for all species, rather than delving too much into the subspecies level. The layout starts with an introduction followed by 800 pages comprising individual species illustrations and maps. There are also Appendices covering extinct species, differences in nomenclature, country codes, reference maps and one country endemics. The introduction sets out what to expect from each species account. As well as one or more illustrations for each species there is a range map showing wintering, breeding and residency areas. In addition, the body length of the species and its altitudinal range are given along with the current IUCN Red List of Extinction Risk category (ranging from Least Concern to Extinct in the Wild). The number of subspecies is given and distinct subspecies are also illustrated. There is a square checkbox for you to keep a personal record if required. There are two other key pieces of information in the species accounts. The first is a four segment circle called the taxonomic circle. The introduction goes into some detail about the four different world checklists that currently exist and how, whilst largely overlapping, they each have their own approach to the splitting and lumping of species based on different criteria. The taxonomic circle aims to summarise the differences between the four lists. This probably is more of interest to those with a deeper interest in ornithological taxonomy and does take a bit of scrutiny to understand. The second is the QR code for each species. This links via a smart phone app to the online resources of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and it gives you access to all sorts of detailed information including photos, calls and video recordings. This links the book with the increasingly digital world many people live in. The more I looked at this book the more I liked it. I am going to use it to keep my world list and will use the QR codes to get more detailed info on any species I am interested in. For those who cannot afford or do not want all the previous volumes this might indeed open up access to the fascinating world of bird species.

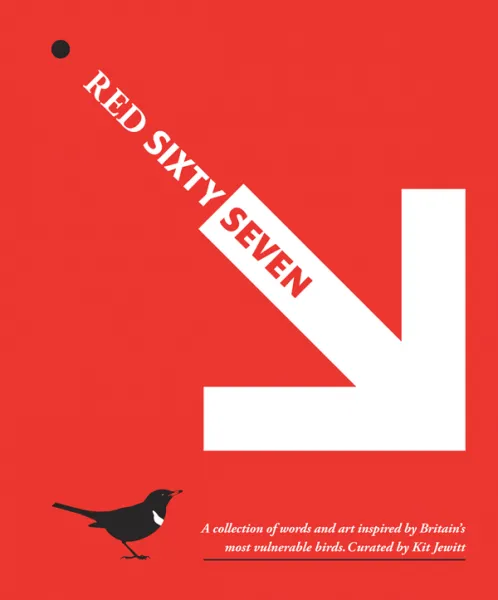

Red Sixty Seven

Author: 67 authors and 67 artists & curated by Kit Jewitt

Publisher: British Trust for Ornithology

Published: 2020

While public support for conservation continues to grow, the funding provided by governments has fallen away. Within the UK, public sector spending on biodiversity, expressed as a proportion of GDP, has fallen by 42% since 2008/09. This means conservationists have to prioritise where their limited funds should be spent, typically directing resources to either the best places for nature or the species in most need of our help. The identification of places and species is made possible by monitoring data, much of it collected by organisations like BTO. Identifying species in need The standard global approach to identifying species in need is to assess their risk of extinction (the IUCN’s Red List approach). For UK birds, however, we consider a broader range of issues and use these to assign each native species to one of three Birds of Conservation Concern (BoCC) categories based on strict criteria. These relate to whether or not the species is listed as ‘Globally Threatened’ on the IUCN Red List; whether there has been a historical decline in the breeding population; a more recent decline in the breeding population; a decline in the non-breeding population; a decline in breeding range; or a decline in non-breeding range. For each of these criteria there are thresholds. If the species meets the ‘Red’ thresholds then it is placed on the Red List; if not, then it might meet lower thresholds and be placed on the Amber List. If a species does not meet any of the thresholds then it is reenlisted. The BoCC review, published in 2015, made for sobering reading, with 67 species on the Red List (27.5% of the 244 species assessed). Raising awareness While the BoCC process provides a focus for conservation practitioners, researchers and policy-makers, it is also important to increase wider engagement with our most at-risk birds. Some Red-listed species are familiar ‘garden’ or ‘farmland’ birds, such as House Sparrow, Song Thrush, Lapwing and Yellowhammer, but many people will be unaware of the challenges they face. A new project, called Red Sixty Seven, has addressed this. Red Sixty Seven is the brainchild of Kit Jewitt, who many will know through his online alter ego YOLOBirder. The concept was simple; a book featuring all 67 Red-listed birds, each illustrated by a different artist and accompanied by a personal story from a diverse collection of writers. In addition to the money raised from book sales, the 67 artworks were auctioned, with all proceeds split between BTO and RSPB. The whole project was made possible because of the generosity of the writers and artists, who included Ann Cleeves, Patrick Barkham, Mark Cocker, Darren Woodhead, Carry Akroyd and Derek Robertson, all of whom gave their work for free. The success of Red Sixty Seven has been staggering, the artworks selling out within just a few hours. The entire first print run sold out in under a month, and two-thirds of the second print had sold before the books had even been delivered by the printer. A third print run followed. Importantly, the project has achieved significant reach across social media and in the press, introducing new audiences to these 67 birds and the work being done to conserve them. The book has been described as ‘67 love letters to our most vulnerable species’. It is a project of which we are rightly proud.

Fragile: Birds, Eggs and Habitats

Author: Colin Prior

Publisher: Merrell Publishers, London

Published: 2020

The acclaimed Scottish photographer Colin Prior is more usually associated with stunningly evocative panoramic landscapes of his homeland and further afield, but for his latest project the artist has returned to one of his first loves, birds; a passion nurtured while growing up on the edge of a Glasgow suburb. Like many however, Colin is acutely aware of the staggering decline of many species and the loss of the habitats they depend upon. Fragile is both inspired by and acts as a metaphor highlighting such demise. Fragile presents exquisite images of the eggs of a diverse range of bird species found throughout Scotland, paired with carefully chosen photographs of the landscapes in which they may be found. With incredibly detailed photographs of mostly a single egg for each species, prominently displayed on a white page uncluttered with extensive text, opposite the earthy hues of the Scottish landscape, the result really is eye-catching and quite unique. As a work of art Fragile represents a meticulous labour of love, with Colin’s passion for the natural world clearly evidenced in the colours of the landscapes, captured at just the right time of year to perfectly complement the markings of the eggs themselves. The maroon speckling overlaying the pale blue of a Bullfinch egg for example, pleasingly matches the purple and silver hues of winter birch and ash trees on the hillside of Glen Shira, Inveraray. Amazingly, every egg photograph is a focus stack of between 40 and 80 individual shots, combined using specialist software to produce images that are breathtakingly sharp throughout. The diptychs of eggs and their landscapes are organised into chapters according to habitat, ranging from mountain to rocky coast. For most, it is likely that Fragile would be considered a 'coffee table' book, making a worthy addition to any collection; yet this beautifully presented work is, in many ways, so much more than that. Instead, Fragile not only documents a remarkable project ten years in the making, but also that of the delicate connections between the implicitly fragile eggs featured therein, the vulnerability of so many of our bird populations, and the threatened habitats within which they are found. These connections are ably examined in an introductory essay by Professor Des Thompson, principal advisor on Science and Biodiversity with NatureScot, in which he considers the fascinating form and vital function of birds’ eggs, the rapidly changing landscapes that our birds inhabit, and the damage that humanity has caused to those environments as evidenced through eggs themselves. The eggs photographed for the book are sourced from the collection held by National Museums Scotland in Edinburgh and the scientific value of such collections is discussed by Bob McGowan, a Senior Curator in the Department of Natural Sciences. He sensitively reviews the history of egg collecting and the unquestionable ethics outlawing what was once a legitimate pursuit in the UK. This narrative is framed by the opportunity museum collections provide for conservation research, most notably that describing the precipitous decline of raptor populations resulting from widespread organochlorine pesticide use in agriculture during the previous century. Fragile is first and foremost a book of photography, and devotees of Colin’s Scottish landscapes will not be disappointed. On the other hand, readers hoping to gain further insight into the nesting ecology of the included species will find themselves left wanting. The essays are insightful, and along with Colin’s account of his lifelong inspiration for the project and the creative process, add the necessary scientific context to the work. Sadly, there are one or two issues with the book, not least of which is the thickness of the paper stock used throughout, the lack of any FSC certification, and the printing outsourced to China; this disappoints and grates slightly with the intended environmental message. Concerning the contents, it would perhaps have been useful to have included, for each egg, an indication of their life-size, perhaps by including a scale bar below the caption; and whilst the duplication of some species within the same habitat chapter may serve to highlight the bewildering variety of colouration and marking, this comes at the expense of excluding others.

Lincolnshire Bird Atlas 1980-1999

Author: Lincolnshire Bird Club

Publisher: Lincolnshire Bird Club

Published: 2020

Published soon after the series of local atlases that coincided with Bird Atlas 2007–11, you might think the Lincolnshire Bird Atlas would span a similar period. You might expect a lavishly illustrated atlas with up to date distribution maps. You’d be wrong on both counts because this is a very different atlas, one from a different era. An atlas that nearly never was. There’s a temptation with any atlas to jump straight to the maps but I always recommend readers look carefully at the introductory chapters so they understand how to interpret what follows. This is especially important with the Lincolnshire Bird Atlas because it details the rocky road this project took, from inception in 1980, mothballing in the late 1990s, and three failed revivals in the 2000s before the project was finally brought to publication during 2017–20. It describes how ‘IT archaeology’ was required to access and extract maps and species accounts produced in the late 1990s. These have been faithfully reproduced, providing a snapshot into the past – not only revealing what bird distributions looked like in the late 20th century, but also what the experts of the day knew about the birds of their county. It documents the distribution of 129 breeding species based on fieldwork between 1980 and 1995, plus short accounts for a further 241 non-breeding species recorded up to 1999. Without the benefit of latterly arriving egrets, buzzards and kites, it is a stark reminder of what we have lost - wall-to-wall Turtle Doves, Redshanks breeding in every saltmarsh-dominated tetrad, and Swallows in over 90% of tetrads. This book is an important baseline documenting the status and fine-scale distribution of birds in England’s second largest county. I grew up in the Lincolnshire Fens, and fieldwork for this atlas was the first systematic surveying I ever did, so I am delighted to see it published. It brings back memories of finding breeding Lesser Spotted Woodpeckers and searching for Long-eared Owls in Fenland spinneys. The Lincolnshire Bird Atlas may not be as colourful or elegantly designed as some modern atlases, but there are very good reasons for that and I think it would be a mistake to judge it harshly. It contains a wealth of information that was almost lost, but here it is preserved for future generations of researchers and birders I recommend this book to everyone who took part and to anyone with an interest in Lincolnshire’s birds.

My Birding Life

Author: Moss Taylor

Publisher: Wren Publishing, Sheringham

Published: 2020

Ask any birder or naturalist that lives in Norfolk if they know the name Moss Taylor and invariably, they will say "yes", and I suspect the majority will have met him too, and of these many know him as a friend. He is a man, on first meeting, you are unlikely to forget! Moss has been a keen birder since 1953 and a Norfolk resident from 1969 to the present day. He has also been a qualified ringer for over 50 years, only recently surrendering his permit after some of the most pioneering ringing endeavours seen in Norfolk in the 1970s and 80s. He is perhaps best known though through his prolific publishing efforts – some 10 book titles to date not to mention 850 other articles for magazines and newspaper columns. It would be a mistake to think that his latest offering My Birding Life is no more than a birder reminiscing about the past and the good old days! Having said that it is very obvious from his accounts of birding in Norfolk in the 1970s that they were indeed glorious, good old days. The history of Norfolk birding on the North Norfolk coast is rich and extraordinary as illustrated in Moss’s accounts and I defy even the hardest nosed young birder not to be amazed by the birds recorded in that decade but also by the events and personalities involved in establishing what we now take for granted as the mainstream channels for our birding news. What is important in these historic accounts (chapters 4,5 and 6) is that they are now documented for posterity’s sake, rather than lost and forgotten, thanks to Moss’s detective work and his obsessive interest in finding and obtaining historic documents, photographs and artefacts – everything from notebooks from Nancy’s Café (Cley) and Richard Richardson illustrations and paintings to old and rare Norfolk natural history books. Moss is also a much-travelled birder to many parts of the world. His early excursions were to remote parts of North Africa as part of ringing expeditions to study migration, where members, on one expedition, came perilously close to losing their lives due to flash flooding, His later travels were tame and more measured by comparison, either on organised birding tours or as a lecturer on cruise ships. Even if organised tour trips and cruise ships aren’t your thing you will still find these accounts fascinating and full of incidents and humour! Although I have known Moss for nearly 50 years, what I had not appreciated about him is his phenomenal ability to recall detail of a story or event, as witnessed throughout the book. It must surely be a result of extensive note taking (though I have never seen him write a dot of a note when I have been birding with him!), which, if true, must take up more time than his birding! It’s almost as if he decided in his early birding career that "one day I will write a book on My Birding Life!" In the unlikely event that you have never heard of Moss Taylor I guarantee that you will find this a fascinating read.

Rebirding: Restoring Britain's Birds

Author: Benedict Macdonald

Publisher: Pelagic Publishing, Exeter

Published: 2019

One of the few personal joys of these recent challenging months is that I’ve had the time to read many nature books. Some of which have been thrilling reads, and today I thought I would share my thoughts on one of the most revolutionary nature publications in recent times, Rebirding. Rebirding explores how humans have shaped British ecosystems since the end of the last ice age, and how recent farming methods have led to impoverished ecosystems and serious declines in many of our native species. Undeterred however, author Benedict Macdonald presents us with bold new solutions that could bring our threatened wildlife back from the brink. Until the release of Rebirding, Benedict Macdonald was a relatively unknown writer and naturalist, though many would have been aware of his contributions over the years to wildlife magazines such as Birdwatching and Nature’s Home. He also co-produced the Netflix series Our Planet, helping with the script with his knowledge of natural history. Rebirding is his book debut, and I was very much looking forward to reading what visions he has for restoring Britain’s wildlife. Interest in the subject of restoration ecology - or rewilding - has exploded in recent years, with multiple books, such as Feral and Wilding, winning several awards, so I was also wondering whether this book would be as compelling as some of the others. He didn’t disappoint. Rebirding, for the most part, is a fantastic read. What Macdonald has produced here is a gloriously ambitious yet theoretically achievable manifesto to save Britain's wildlife, and he’s done so in a very readable way. The book is extremely thorough, with hundreds of references cited throughout the book, though it doesn’t read like an academic journal. It’s very easy to follow, and I think this will be a fascinating read even to those with just a casual interest in saving nature. The first half of the book focuses more on how Britain once looked in its natural state, and what species it has lost over the last few thousand years. Such species include those that are globally extinct, like mammoths, rhinos and aurochs, and species that exist elsewhere, such as bears, wolves and lynx. For me, reading such passages caused some mixed emotions. On the one hand, sadness that we’ve lost these species, but on the other, the thought of these animals walking around together in the same area made me feel quite tranquil. Macdonald encourages such imagination by often starting chapters with a description of walking around a wildlife-rich landscape which could be in our grasps if we conserve our wildlife properly. Although it does feel a little repetitive, often they make you want to jump into the pages themselves to see such a world yourself. The book is compelling as it is beautiful, and one of the main reasons for this is that Macdonald tells us that much of what we think is right for wildlife, is in fact wrong. I’m sure many of us have a picture of pre-human Britain as being one dense forest, but Macdonald wastes no time in telling us that was simply never the case, and instead, Britain once contained a dynamic mixture of many habitats, such as grasslands, scrub, and open woodlands that were kept in balance by mammalian herbivores. These are the landscapes we should be attempting to restore, and we should not be content with simply planting a load of trees (which often form wildlife deserts). Another example is that, while most of us would think that national parks are havens for wildlife, in reality, a lot are poorly managed for wildlife to thrive. This is also the case for many of our protected sites and nature reserves, which are often over-managed to accommodate only a few species. Yet in such passages he never descends too much into bitter pessimism, and he keeps such chapters light and optimistic by offering slight improvements that could enhance their biodiversity. When talking about what we can do to rescue our wildlife from the brink - which is the main focus of the second half of the book - what repeatedly emerges is that there are many economic incentives to rewilding. A key fact to remember is that only 6% of Britain's surface is built upon, so there is huge scope to change our countryside in ways that could create employment and economic prosperity, and several examples are explored in this book. Such ideas quash the opinion that conservation is an economic burden that hampers progress, and what makes these suggestions so interesting is that a lot of them are based on models and case studies that currently exist elsewhere in Europe in countries with much higher levels of biodiversity. Sometimes it makes you wonder why we haven’t adopted them all this time. The book will of course be a better read for those who are already familiar with the birds found in Britain, but not massively so, as the ecology of a few species that appear repeatedly throughout the book are described in its earlier chapters. Despite its title, this is not solely a book that will appeal to birders. Birds of course are mentioned throughout, but the types of ecosystems that Macdonald is hoping to restore will also be those with higher diversity of other animal groups, such as insects and mammals and reptiles. Birds of course have co-evolved with other faunal groups for millions of years, so naturally optimum habitats for bird communities will also be the optimum habitats for these other groups. For a book of under 300 pages, Rebirding is unusual in having multiple subheadings throughout its chapters. Some of these are better placed than others, but I eventually grew to like them, because one thing that you will struggle to do with this book is to binge-read it. Many of the chapters reveal such bold and thought-provoking ideas that at times you just want to stop at certain points and let them wash over you for a while. That’s how powerful this book is at times. The book isn’t perfect however. Occasionally, I felt that some case studies could have been fleshed out a bit more, especially the Netherlands Oostavaardersplassen project, which is one of the first case studies he talks about in this book. I also felt that Chapter 2, which goes through the changes that Britain has undergone over the past few centuries, felt a bit disjointed, with it not knowing whether to focus on landscape changes over time or on the fortunes of particular species. But these are just small gripes in what is an amazing writing debut. I don’t often comment about the cover of a book, but I think this one deserves some attention. Looking at the habitat in the background, it’s hard to define what sort of landscape you’re in, as you can see wetland species as well as those of woodland and grasslands. But of course, this mosaic of different habitats in one area is exactly what Macdonald is hoping for us to achieve as that’s how it looked before human intervention. But this isn’t a hypothetical landscape; In the background you can see the Burrow Mump, which is a famous landmark of the Somerset levels, so you can see that this is his vision for the region. In the foreground is a transparent ‘ghost’ of a Dalmation Pelican, reminding us that this species was once breeding in Britain, and I think having this famous and charismatic species as the main focus point of the cover was a very good idea. The colours are also impressive. I think the orange and yellow background colour gives an impression of dawn, which is fitting, as the reintroduction of species back into Britain will itself be a new dawn for how we treat our wildlife and landscapes in a sustainable way. Overall, Rebirding is a fantastic book that will likely inspire you to get actively involved in saving Britain's wildlife. This is a read you won’t regret.

Britain's Habitats: a Field Guide to the Wildlife Habitats of Great Britain and Ireland

Author: Sophie Lake, Durwyn Liley, Robert Still & Andy Swash

Publisher: Princeton University Press, Princeton & Oxford

Published: 2020

To understand the distribution of our birds it very much helps if we know the preferred habitats of each species. For example, Knot winter on mudflats, Dartford Warblers live on lowland heaths and Dotterel nest on mountain tops. But habitats are messy things. We all have an idea of what we mean by a woodland, but how many types of woodland are there, and how do they differ? This book will help you get at the details, and details can prove to be important. This authoritative guide lists 66 distinct habitats of Britain (and Ireland, contrary to the book’s name) and divides them into 10 broad groups: Woodlands, Scrub, Heathlands, Grasslands, Mountains, Rocky Habitats, Wetlands, Freshwaters, Coastal Habitats and ‘Other’ Habitats. The meat of the book is taken up with detailed descriptions of particular habitats. Each has a map showing: its extent in Britain and Ireland; a discussion of its origins and development; relationships to other habitats; particular conservation issues; and key species to look out for. There are notes on how to recognise each habitat type, and each account is lavishly illustrated with many excellent photos of both examples of the habitat and a few relevant species. The accounts are preceded by a good introduction setting out factors influencing habitats. For the more technical user, there is a particularly useful table at the end of the book comparing different habitat classification systems currently in use. It is worth noting that this is the second edition of this guide, but it has been extensively revamped in terms of format and content. It is now an even more useful and attractive book than in its previous incarnation. Highly recommended.

Goshawk Summer: A New Forest Season Unlike Any Other

Author: James Aldred

Publisher: Elliot & Thompson, London

Published: 2021

Award-winning documentary film-maker James Aldred spent the spring and summer of 2020 filming Goshawks in the New Forest, his childhood home. This book, presented in an extended diary form, catalogues the author’s time with the Goshawks and many of the Forest’s other inhabitants. The text is punchy, with short, sometimes staccato sentences and delivers a very personal take on these magnificent birds, and much else besides. The diary format means that the text jumps around a bit, presenting the reader with short accounts of other encounters – a swan on the A36, an active Buzzard nest down the slope from where he is filming – so don’t expect a developing central narrative. Having said that, this is still an interesting read, full of closely observed detail of Goshawk behaviour and the world of the wildlife film-maker. This detail reveals an intimacy, formed between the photographer and his subject, which comes across in the text and transports the reader to the hide and the unfolding drama of this Goshawk breeding attempt. This intimacy is perhaps most evident in a passage describing how the author exits the hide at the end of a filming session. Aided by a colleague who walks in below, he has to judge the sitting bird’s response and you can feel the tension growing as he plans his exit under the bird’s fierce glare. It is a wonderful moment, and one of many throughout this engaging book.