Read reviews of the books we hold in the Chris Mead Library, written by our in-house experts. A selection of book reviews also features in our members’ magazine, BTO News.

Featured review

All the Birds of the World

Lynx have had a long-term project to produce an exhaustive guide to the birds of the world. It started out with the 17 volumes of the Handbook of the Birds of the World (1992–2013) which has family and species accounts for all birds. This was followed by the two volumes of the Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World (2014–2016). They have now published the third and final stage of this avian odyssey with this current book.

Search settings

The Role of Birds in World War One: How Ornithology Helped to Win the Great War

Author: Nicholas Milton

Publisher: Pen & Sword History, Barnsley

Published: 2022

In a follow-up to last year’s The Role of Birds in World War Two: How Ornithology Helped to Win the War, Nicholas Milton has produced another fascinating book exploring the role played by birds in 20th century conflict. Described as “The Best Birdwatching Army Ever Sent to War”, the British Expeditionary Force included hundreds of both professional and amateur ornithologists. This book covers a number of their stories, starting with the Foreign Secretary at the outbreak of war, Sir Edward Grey, winding its way through individuals such as the British Army’s Official Rat Catcher, Philip Gosse, and Thomas Mills, who had the idea to try to gain military advantage by training gulls at sea to detect submarine periscopes. The birds themselves are by no means forgotten, from reports of House Martins sensing overhead Zeppelins to the work of the British Army Carrier Pigeon Service. Birdwatching increased in popularity throughout the war, and it became one of the most popular pastimes in the trenches. From the Skylark, whose song could still be heard over the din of battle, to the report of a Blackbird so undisturbed by the fighting that it built its nest inside a horse-drawn field gun, the book highlights the resilience of nature and how this contributed to the soldiers’ welfare and mental health. As well as more traditional birdwatching it also highlights opportunities that presented themselves for slightly more unusual research, such as the French pilot who published observations on bird flight which he had made at altitude. The book concludes with an ‘Ornithological Roll of Honour’, a tribute to 37 ornithologists who lost their lives during the Great War. Comprising professional ornithologists, amateur birders, bird artists and photographers, the stories of their lives and their contribution to ornithology before and during the war serve as a poignant reminder of what they might have gone on to achieve. Like it’s World War Two companion, this is an easy-to-read work packed with interesting and often moving details about an unusual subject. With consideration of both ornithology and historical context, it should appeal to anyone with an interest in either field.

Tracks & Signs of the Birds of Britain and Europe

Author: Roy Brown, John Ferguson, Michael Lawrence & David Lees

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, London

Published: 2021

I suspect that the vast majority of naturalists and birdwatchers have a few feathers, skulls and general bird detritus somewhere in their possession. These can serve as a souvenir from a trip, a useful reference, or worth having simply to appreciate their beauty or structure. Knowing where these objects come from adds a lot to their meaning. This is where Tracks & Signs of the Birds of Britain and Europe steps in. This is the third edition of this book, with this latest version seeing a large amount of content added compared to the first edition (that I own). The page count has nearly doubled, with each topic receiving expansions, fresh illustrations (19 new colour plates and hundreds of photographs) and new knowledge. Footprints, feathers, pellets, droppings and bones are a few topics covered. The book is approached from the perspective of a field naturalist, with details on how you will find these objects and signs while on a walk, making it particularly useful for how most of us will discover footprints or pellets. Some signs are contrasted with those left by mammals, helping avoid embarrassing mix-ups. Around half of the book is dedicated to feathers and skulls, with the overwhelming majority of species covered, with a range of feathers for each bird. This may be the limit of the book, as there is always a good chance the feather you have found won’t be covered. However, it remains a great jumping-off point for the feather enthusiast. The skulls are wonderfully illustrated, and with a small amount of care, you would likely get to a species-level ID even with very similar species. Those who only birdwatch in the UK may find frustration in the number of pages covering species they are unlikely to encounter, but I took great pleasure in seeing the footprints of a Great White Pelican or Crane replicated in life-size. For those whose shelves are already crammed with field guides of birds, this is a must-own, adding extra depth to the knowledge and enjoyment we get from watching birds and making sure that wing feather on your mantelpiece is properly identified!

The Bird Name Book

Author: Susan Myers

Publisher: Princeton University Press, Princeton & Oxford

Published: 2022

In style, this very engaging book sits somewhere between the terse Helm dictionary of scientific bird names (by James Jobling) and Ray Reedman’s much more discursive Lapwings, Loons and Lousy Jacks. In content too. The subtitle here is all important - “A history of English bird names”. It aims to cover the ‘common’ English names of all bird groupings (from Accentor to Zeledonia). So no explanations of scientific names here – except where they have been transferred into the “English” name – and no specific epithets, so while “gull” is there, there is no entry for James Clark Ross. The names follow “standard” usage, but are refreshingly global, so both diver/loon and skua/jaeger are there, along with, for example, many Australasian names. Although there are some autochthonyms (names borrowed from another language), and, no, I didn’t know that’s what they were called either, such as Ākohekohe (Hawai’ian), Kagu (Kanak) or Ibon (Tagalog), other names, especially where they refer to individual species, perhaps not unreasonably in terms of length, are missing – so no Bonxie or Tystie, for example. This led me to wonder how many potential autochthonyms we missed out on as early European explorers ran roughshod over much of the world? It is nice that the author nods to the sensitivities around some names without erasing them completely – this is a “history” after all. Most of the entries are short, less than a page, with a generous helping of high-quality photographs and historical illustrations, so this is a great book for dipping into and there is much to learn, but it is perhaps not complete enough to be a true reference book.

A Newsworthy Naturalist: the Life of William Yarrell

Author: Christine E. Jackson

Publisher: John Beaufoy Publishing, Oxford

Published: 2022

Yarrell’s is a name that you have probably come across, if only through its association with the British race of White Wagtail – which we know as Pied Wagtail or Motacilla alba yarrellii. He is, however, a somewhat distant figure now, whose significant contributions to the study of birds (and fish) have largely been forgotten. Yarrell’s A History of British Fishes and A History of British Birds, published in the 1830s and 1840s respectively, were the main reference works on these subjects for the remainder of the century. As a partner in a newspaper agency and bookseller, Yarrell was well placed to interact with other eminent naturalists, including Charles Darwin and John Gould, and he became a central figure in the study of ornithology at this time, including throughboth the Linnean and Zoological Societies. He was also the first to recognise that Bewick’s Swan was a distinct species from Whooper Swan, something that helped to make his name. This new book, published in association with the British Ornithologists’ Club, provides significant detail on his life and achievements, and it is through the thoroughly researched text that we can glimpse something of the man himself. The initial six chapters are structured around a chronological framework, although these do jump about a bit in places and there is some repetition of facts. These outline the development of Yarrell’s interests (which were broad and deep) and his ‘career’ as a gentleman naturalist. The final three chapters, together with a series of shorter end sections, explore his interests, publications (there were at least 80 papers published in scientific journals), and the societies with which he was involved. Accounts of his correspondence and where this is held, together with a list of known portraits, deliver additional detail that serves to underline the central role that Yarrell held within the wider sphere of natural history interest. Yarrell was, for example, seemingly influential in directing Charles Darwin in his early studies and pivotal in the latter’s decision to publish the zoology of the Beagle voyage. Being able to glimpse the man behind the name, and to discover his incredibly productive research career, shines a timely light on our ornithological past.

Birds of the Lesser Antilles: A Photographic Guide

Author: Ryan Chenery

Publisher: Helm, London

Published: 2022

This guide serves as a colourful who’s who of the Lesser Antilles’ birdlife designed for casual birders visiting the region, including those on a non-birding holiday who would nonetheless appreciate being able to identify the avian species they encounter on their travels. I am myself no means an ornithological expert, though my partner is, and we have been on many a holiday on which I have repeatedly asked ‘what’s that bird?’ or ‘what’s that I can hear singing?’. Sometimes having a weighty bird guide with endless species can be a bit intimidating to a beginner. Birds of the Lesser Antilles is a much more beginner-friendly book for nature enthusiasts such as myself. The description of the different bird habitats across the region is a useful tool, helping to put species in context. One of my passions is spiders, and I usually assess the habitat I find them in before I attempt to identify them. A summary of what can be seen at different times of year helps narrow the search, too. It’s also handy if planning when to visit. While not a complete list of species of the area, a collection of over 200 of the more common species is still a brilliant resource for the travelling birder, and I certainly recognised some of the species from my own visit to the Caribbean. The title is somewhat misleading, however, as the book does not cover all of the islands of the Lesser Antilles, for example Trinidad and Tobago are not included. Clear, engaging photos alongside descriptions without overly technical language are a good starting point for identification for beginners. Notes on vocalisations and where to find different species are a thoughtful touch as well. All in all, this book is very accessible, particularly for amateur birders like myself. It’s a very good starting point and I would happily take it with me on a trip to the Lesser Antilles.

Where to Watch Birds in East Anglia: Cambridgeshire, Norfolk & Suffolk

Author: David Callahan

Publisher: Helm, London

Published: 2020

Courtesy of its geographic position, diversity of lowland habitats and extensive coastline, East Anglia is high on the list of desirable UK birding destinations. Even in this age of web- and app-based resources, there is still a place for ‘where to watch’ books and this comprehensive site guide to such an attractive birding region will be of interest to local and visiting birdwatchers alike. Overall, the book does a very good job of cramming in lots of information in a manageable format, including a liberal scattering of clear and largely accurate maps, and tabular summaries of expected species for all the main sites. One disadvantage of a printed site guide is the rate at which bird distributions are changing but the perilous status of Willow Tit in East Anglia, for example, is reflected as accurately as can be expected for a book published in 2020. Perhaps more surprising is the inclusion of at least one site that had already ceased to exist as a gull-watching spot long before the book’s publication: Blackborough End Tip. I initially found the indexing system confusing, until I realised that the numbers alongside species names refer to sites rather than page numbers. This can make it hard to pin down mentions of a given species, particularly as some sites span up to six pages. Whilst recognising that public transport is limited in many parts of East Anglia, and cycling infrastructure less well developed than it should be, it was disappointing that many ‘Finding the site’ sections do not offer alternatives to the private car, nor information about access for people with a mobility impairment. Where either of these are mentioned, it is typically at the end of the section, rather than the start – an opportunity missed. Locations are grouped in six sections: Cambridgeshire, The Fens and the Ouse Washes, Norfolk, Breckland, The Broads National Park, and Suffolk. The choice of sections makes perfect sense, even though some straddle one or even two county boundaries. However, considering that the Broads National Park is treated separately from Norfolk and Suffolk, it was odd to find sites such as Carlton Marshes SWT, whose website describes it as “the southern gateway to the Broads National Park”, in the Suffolk section. In contrast, all the sites covered in The Broads National Park section are in Norfolk. In addition to the main sites, there are also ‘subsidiary’ sites; it would have been good to see this term explicitly defined in ‘How to use this book’. Site names are listed in the Contents, by area, but not indexed at the end. This might make it hard to navigate for anyone who has heard a particular site being mentioned but is not sure which part of East Anglia it is in. Having visited most of the ~150 sites covered, and being familiar with around half of them, I found the majority of entries to be accurate, informative and enticing. There are some minor inaccuracies, such as the suggestion that Wood Sandpiper is “among the scarcer species” that can be encountered at RSPB Snettisham, whilst White-rumped Sandpiper is described as a “remote possibility” (along with Pectoral and Buff-breasted Sandpipers). In reality, White-rumped Sandpiper is far more frequently recorded than Wood Sandpiper there, due to the largely saline/brackish nature of the wader habitat. One site inclusion and one omission caught my eye: Scolt Head Island is given two pages, including a small map that is of very limited value. However, this site is difficult to reach and explore, hence not suitable for one of the book’s key target audiences (according to the introduction): first-time visitors to the region. In contrast, BTO Nunnery Lakes, with its diverse mix of wetland, woodland and drier habitats – and within easy reach of several key Breckland sites – does not even feature as a subsidiary site. By and large though, this book stakes a strong claim to being “the definitive guide to the birding highlights of the region”, as stated on the back cover, and certainly “contains a comprehensive review of all the major sites, and many lesser-known ones” that will interest any birdwatcher destined for this bird-rich corner of Britain.

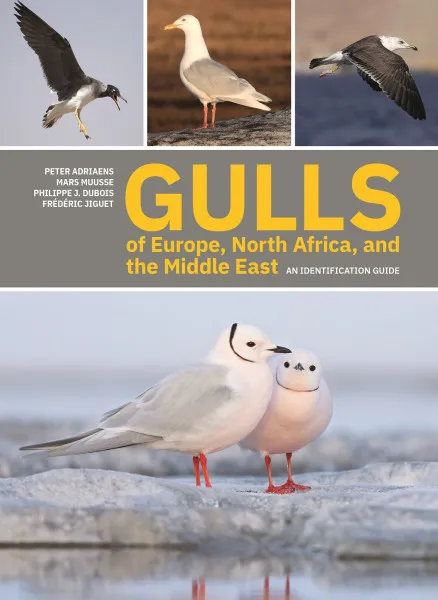

Gulls of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East: An Identification Guide

Author: Peter Adriaens, Mars Muusse, Philippe J. Dubois & Frédéric Jiguet

Publisher: Princeton University Press, Princeton & Oxford

Published: 2021

Although I do not condone it, I (somewhat) understand why non-birdy people often refer to all gulls as ‘seagulls’. Until you get your eye in, some species do look similar to one another. This statement may be controversial, but it is safer to say that even for more experienced birders, gulls can be tricky. This is especially true when identifying juveniles. The authors of Gulls of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East: An Identification Guide aimed to tackle this problem by creating an updated resource which allows learners to hone their skills. The result is a beautiful book that will both satisfy and create gull-lovers. Containing 45 species (including some hybrids) from across the ‘wider Western Palearctic’ the book is remarkably comprehensive. Each species is afforded multiple pages, divided by adult, first, second and third cycle forms. This maximises your chances of identifying a bird, no matter when in its life you happen to spot it. Through the use of 1,400 high-quality images, the book provides guidance on how to delve deeper into minutiae of species identification. The labelling focuses on subtle characteristics such as fine-scale plumage detail and eye colour, which may be key indicators when distinguishing between look-alikes. One particularly handy tool is the ‘similar species’ box, which directly compares each species with an illustrated list of similar gulls, thereby helping learners avoid common mistakes. I would not gift this book to a beginner. Its technicality might be unhelpful or intimidating for those just starting out. It is, however, perfect for two groups of people: those who are interested in becoming an expert in bird identification and those who love gulls. The former group will find a book crammed with good advice, while the latter will rejoice to see their favourite birds displayed in such a rich format.

Birds of South Africa

Author: Adam Riley

Publisher: Helm, London

Published: 2022

For budding birders or those unfamiliar with African avifauna, the prospect of identifying birds in a biodiversity-rich country like South Africa might feel overwhelming. Birds of South Africa aims to provide a lifeline for this untapped audience. Pitching itself as a comprehensive beginner’s guide, the book provides just enough information on the appearance, habitats and behaviour of South Africa’s most commonly seen species to permit a positive identification. The vibrant and informative pictures encourage easy species comparison and thus help learners to refine their skills. An exciting addition is an extensive list of the nation’s best birding sites, which had me itching to make a mad dash for the airport. The book is impressively compact. It contains over 340 species, and although four species sometimes fill a two-page spread, it rarely feels cluttered. This portability gives it a notable advantage over other, similar titles but inevitably, sacrifices have been made in terms of detail. Its lack of distribution maps might frustrate seasoned wildlife tourists; however, Birds of South Africa is not aimed at serious birdwatchers who are setting off on that once-in-a-lifetime trip to the Kruger. Instead, it is perfect for the casual enthusiast who wishes to take a decent stab at identifying the birds they see on their holiday, without having to spend hours poring over a heavy book to do so.

Birds of the Middle East: A Photographic Guide

Author: Abdulrahman Al-Sirhan, Jens Eriksen & Richard Porter

Publisher: Helm, London

Published: 2022

The Middle East is something of an international stepping stone for both migratory birds and people travelling between Europe, Africa and Asia. For birdwatchers stopping over in this part of the world, a rich and unique avifauna awaits, and this photographic guide provides a perfect introduction. The front cover is adorned with stunning images of a representative selection of the region’s birds: Lichtenstein’s Sandgrouse, Desert Wheatear, Steppe Eagle and Rufous-tailed Scrub Robin. These provide a taster of the fabulous photographs to be found throughout the book; personal favourites include the sentry-like pair of Cream-coloured Coursers and the beautifully-framed White-spectacled Bulbul – the latter an often-underrated species that is largely confined to Turkey and the Arabian Peninsula. The exceptional photography is made all the more impressive by the vast majority of the images clearly having been taken in the region. The introductory section identifies the target audience as “those who on their travels in the Middle East would like to spend some time watching the exciting birds [it offers]” as well as voicing the hope that “it will encourage those who live in the region to take an interest in its wonderful birds and their conservation” – a worthy aim indeed. Next is a summary of some of the challenges facing birds and their habitats in the Middle East, then a short but tantalising overview of some of the top birdwatching locations in each country. The species entries follow directly; given that these account for about 90% of the book, it would have been good to see this section clearly announced. The species accounts are brief but all have a handy ‘Where to see’ paragraph, outlining each bird’s habitat, distribution and seasonal occurrence. Understandably for a book of this nature, a limited selection of plumages are shown. Some of the image choices are a bit perplexing: two images of adult male Little Bittern but none of the less distinctive plumages, and two near-identical portraits of Hamerkop, for example. However, these very minor points don’t detract from a set of accounts that provide a useful amount of information for a well-chosen selection of birds that the target audience could expect to encounter in the region. I certainly echo the closing words on the back cover: “Portable yet authoritative, this is the perfect guide for travellers and birdwatchers visiting this spectacular and bird-rich slice of western Asia.”