Read reviews of the books we hold in the Chris Mead Library, written by our in-house experts. A selection of book reviews also features in our members’ magazine, BTO News.

Featured review

All the Birds of the World

Lynx have had a long-term project to produce an exhaustive guide to the birds of the world. It started out with the 17 volumes of the Handbook of the Birds of the World (1992–2013) which has family and species accounts for all birds. This was followed by the two volumes of the Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World (2014–2016). They have now published the third and final stage of this avian odyssey with this current book.

Search settings

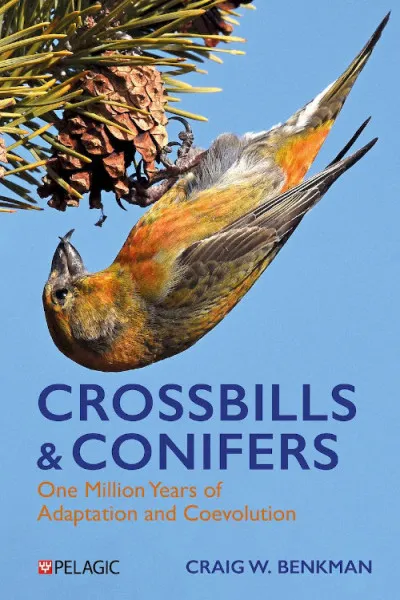

Crossbills & Conifers: One Million Years of Adaptation and Coevolution

Author: Craig W. Benkman

Publisher: Pelagic Publishing, Exeter

Published: 2025

It’s always a thrill to see a Crossbill! I’ll never forget my first sighting of Common Crossbill (Loxia curvirostra), the species that we see most regularly in the UK. It was at Lawson’s Clump in Wareham Forest, Dorset. A flock of around 50 announced their presence with their loud, excitable calls, and they landed at the top of a tall conifer tree. There was a mixture of raspberry red males and bottle green females. It was fascinating to watch them as they fed on seeds from the conifer cones that this fascinating family of birds so relies upon. So, onto this book! In a nutshell (or perhaps in this case, a conifer cone shell, if there is such a thing!) it covers in detail how the different species of crossbill around the world have adapted to feeding on the type of conifer cone that it feeds on. Of course, in order to do this, crossbills are the only species of finches that have crossed mandibles, hence the name. This book explains why having a crossed mandible helps these sturdy finches to prise apart conifer cones in order to feed on the seeds within them. To help illustrate this point, I remember a few years ago when there was a significant irruption of crossbills to the UK. As well as good numbers of Common Crossbills in Thetford Forest near where I was living at the time, there were also small numbers of the more scarce Parrot Crossbill (L. pytyopsittacus) and Two-barred Crossbill (L. leucoptera). This was a real treat, as it provided the rare opportunity to study these two species. Although I didn’t think too much of it at the time, in comparison to Common Crossbill, the ‘Parrots’ had larger beaks and the ‘Two-barreds’ had smaller beaks. Now that I have read this book, I have a better understanding of why this is likely to be! To put it very simply, there are many different types of conifer trees across Europe. Therefore, different species of crossbills have adapted so that their beaks are the right shape and size to feed on their favourite type of conifer cones! This book is predominantly text, but there are several high quality images in it. If you are interested in finding out more about how crossbills, and other species for that matter, have adapted over the years to feed on their favourite foods, you need to read this book! As many of you will know, finches are a very well studied group of birds, mainly in relation to how they have evolved to fit their specific ecological niche. This book is a very welcome addition to that dynasty of research, as crossbills are such fascinating birds!

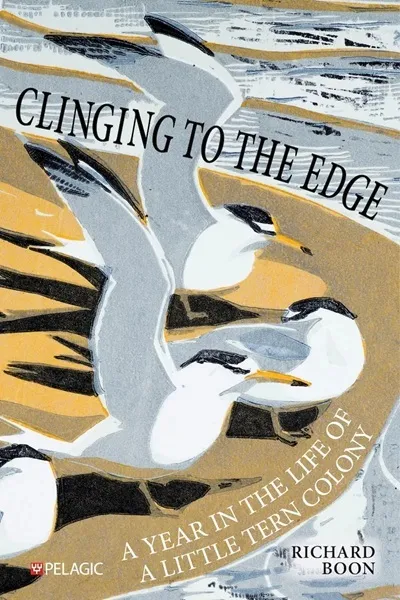

Clinging to the Edge: A Year in the Life of a Little Tern Colony

Author: Richard Boon

Publisher: Pelagic Publishing, Exeter

Published: 2024

Clinging to the Edge is the story of one breeding season at the Beacon Ponds Little Tern colony on the North Sea coast in East Yorkshire. It offers an intimate portrait of these endangered birds, covering everything from foraging and breeding to predators and conservation. The book is written from one person’s perspective, that of Richard Boon who, as Chair of the Beacon Ponds Little Tern Project Management Committee, a volunteer for Spurn Observatory Trust as well as the RSPB and BTO, is best placed to write this 'how-to’ manual and insight in the sharp end of species conservation. Richard’s talent for writing anecdotes about the trials and tribulations of the colony and the detail that is given to the day-to-day monitoring, maintenance of electric fences and protecting the birds from predators such as grass snakes and otters, makes it a charming read. At 152 pages, the book is concise, comprised of monthly accounts spanning from April to August of the 2022 season. You gain a real sense of the area and the colony over this time frame and feel as though you are there, walking across the “ripples, bowls and ridges” of the beach near Spurn Point. This colony was first mentioned in text in John Cordeaux’s 1872 treatise Birds of the Humber District and so Clinging to the Edge continues a tradition of charting the journey of the Beacon Ponds colony. And with Little Tern numbers going the way of so many other species and declining in the UK, putting this knowledge to paper for prosperity is more important now than ever.

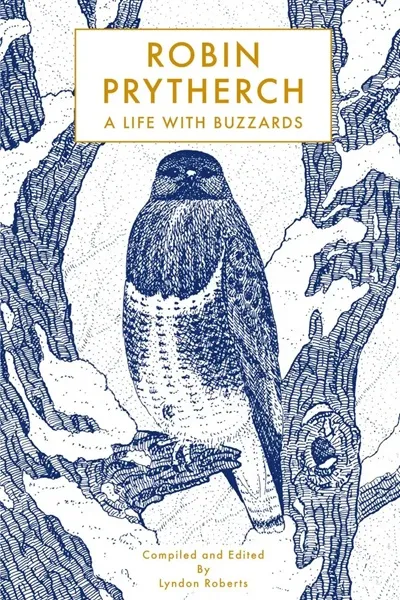

Robin Prytherch: A Life with Buzzards

Author: Robin Prytherch and Lyndon Roberts (ed.)

Publisher: Bristol Books, Bristol

Published: 2024

Robin Prytherch: A Life with Buzzards is a charming anthology of Buzzard scenes sketched by Robin Prytherch and sent out by him to his friends as Christmas cards between 1995 and 2020. These 26 drawings (copied from pen-and-ink drawings or pencil sketches) have been compiled and reproduced here for the first time, along with each year’s accompanying text on the reverse noting Robin’s observations about the single bird, pair, or family unit depicted in each scene. Robin Prytherch (1939–2021) is a well-known name synonymous with Buzzards, having spent over 40 years observing them in a small area of North Somerset, close to his home in Bristol. Although admittedly not a common Christmas card theme, the depth of his knowledge and understanding combined with the hand of a talented artist produced a set of drawings in which the individual personalities of the birds jump off the page. The species’ typical wide variation in plumage is also faithfully depicted, making it easy to match each image to the detailed explanatory description. Watching the birds over multiple decades enabled Robin to build up unparalleled view into their lives and behaviours. The sketches record their changing relationships, territories, fortunes and misfortunes: from Tess, the devoted mother, fledging a staggering 43 chicks over her lifetime, to Gos and his bigamous relationship spanning multiple years. The affection with which Robin held these birds is apparent on every page, making this short book a pleasant and informative read, giving both illustrated and written insight from an expert with real comprehension of Buzzard behaviour.

Encounters with Corvids

Author: Fionn Ó Marcaigh (author), Aga Grandowicz (illustrator)

Publisher: Natural World Publishing, Dublin

Published: 2025

Dr Fionn Ó Marcaigh is a zoologist from Dublin, who received his PhD from Trinity College in 2023 for a thesis on the evolution of birds on islands. Encounters with Corvids is his first published book. Corvids are a much-maligned family of birds that rarely get much positive attention, and I must admit that I’ve never really looked at them myself in any detail before now. This book sets out to change the public perception of ‘crows’ and the author’s empathy towards the seven species of corvids that are found on the island of Ireland is clear, if anthropomorphic at times. Each chapter is superbly illustrated and devoted to a different species, interwoven with a mix of the author’s personal experiences, associated Irish folklore and some fascinating facts about each species. Who would have thought that the Magpie arrived in Ireland only in the late 17th century, given how common and widespread they are now, or that one of the few endemic taxa in Ireland is the subspecies Irish Jay? Corvids also feature often in Irish mythology, notably the Mórrígan (from the Irish ‘Great Queen’), a Celtic goddess of war, who could take the form of a Crow. This stemmed from these corvids’ habit of feeding on human remains left at battlefields, leading them to be associated with warfare. The common theme throughout the book is that corvids are intelligent birds that have adapted so well to the changing landscape of Ireland. Their ability to prosper across intensively managed farmland has led to Ireland having some of the highest densities of Magpie and Hooded Crow in Europe. The author encourages us to celebrate their success rather than treat them unfairly. Perhaps he has a point.

Endemic: Exploring the Wildlife Unique to Britain

Author: James Harding-Morris

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, London

Published: 2025

Endemic. It’s a word that conjures up imaginings of species only found in tropical rainforests or islands. As soon as I read the title of this book I was intrigued. Endemics in Britain. It’s something we don’t often think about. The author, conservationist James Harding-Morris, takes us on his personal journey to discover the species unique to our shores, joining experts working to save them along the way. The book covers species from different taxonomic groups, including plants, mammals, birds, invertebrates and fungi, making you eager to turn every page. The chapters are clearly laid out, so that you can easily dip in and out – however, before I knew it, I was 100 pages in! The language James uses to describe his adventures immerses you into the landscape too. From walks in Scottish pine forests in search of the Scottish Crossbill to meandering along rivers looking for the stonefly Northern February Red and squeezing through dark cave tunnels after the British Cave Shrimp. James is clearly knowledgeable and passionate about wildlife, a true naturalist in all that the word entails. His descriptions of the endemic species he encounters are detailed yet accessible – you can imagine them even if you have never heard of them before. I also appreciated the way James made the species themselves and the experts he met the stars of the work, with his knowledgeable and humorous narration the perfect compliment. There has clearly been a vast amount of research put into the text too. Did you know that the grass Interrupted Brome was declared globally extinct twice? James’ contribution to the fate of the endemics he encountered should also be applauded. From collecting seeds for cultivation to taking the first known photograph of the British False Flat-backed Millipede, James helped further to protect these species. He also raised the question about to what extent conservation is like a beauty contest. The cutest and most appealing species are historically favoured with funding and public support. He questions the perceptions of human value, and highlights the much needed effort to save many endemic species from extinction. Overall, it was a fascinating book, and one I’d recommend to nature enthusiasts. Well actually, to everyone. The work encapsulates the intriguing yet fragile nature of the natural world, and the role we have in its care. I also couldn’t help but wonder what other species there might be still to discover right here in Britain.

Land Beneath the Waves

Author: Nic Wilson

Publisher: Summersdale Publishers, Chichester

Published: 2025

“I am not a memoirist” declares Nic Wilson at the start of her new book. But we do indeed learn a lot about her life in the ensuing 13 chapters, although some details are pieced together with help from other people’s memories, since her own have been lost. This loss emerges to be a result of the trauma of living with chronic illness – not just the author’s own, but her mother’s too. The book explores how women’s health in particular can be dismissed, and how damaging internalising this has been for the author. The book is not written chronologically. It flits back and forth, but along the way covers the author’s childhood, adolescence, university years, her career and her experience of motherhood. Nature is a theme throughout, often in terms of how her knowledge and experience of it has helped her cope with her illness. However, it does not only feature in that way – BTO volunteers might appreciate the account of her father’s nest recording, for example. We also accompany the author on a thorough exploration of the places she’s lived, learning about their ecologies and geologies, and former residents including naturalists and poets. I found I had to concentrate to fully follow the scope of the book, especially in the passages that venture into poetry, and the dreamlike sequences the author uses to convey her experience of pain, anxiety and dissociation. However, I did appreciate the contrast with other nature writing, which can be very expansive, while this focuses on the intimacy with which you can get to know a place, especially when confined by young children, or bedbound by illness. I hope writing this book has been a healing process for Nic Wilson.

Bird School: A Beginner in the Wood

Author: Adam Nicolson

Publisher: William Collins, London

Published: 2025

In Bird School: A Beginner in the Wood, Adam Nicolson charts his journey to learn more about the natural world surrounding his home of over 30 years in the Sussex Weald. From the vantage point of the shed he built in a forgotten field, he takes the reader with him to ‘bird school’ – an exploration prompted by the sights and sounds of the bird life he encounters. Over the course of 13 chapters, he covers a huge amount of information: from individual species such as the Wren with whom he shares his shed for a time, to the broader concepts of migration, rewilding and human intervention. The book closes with a useful chapter on how to attract birds to your garden written by his wife, the horticulturalist Sarah Raven, and a roll-call describing the birds found in his part of Sussex, each with a QR code linking to the appropriate page on the Xeno-canto wildlife sounds website. I first encountered Adam Nicolson through his wonderful 2014 publication The Mighty Dead: Why Homer Matters, and his wide-ranging interests are evident throughout Bird School from classical references to Homer and the pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus to quotations from Shakespeare and Wordsworth. However, at the same time this is a well-researched book packed full of ornithological facts, backed up with data including population graphs adapted from BTO’s own Bird Trends Explorer. Bird School is a fascinating and easy-to-read book, which contains as much of interest to someone starting out with birds as for those who have been attending ‘bird school’ for some time.

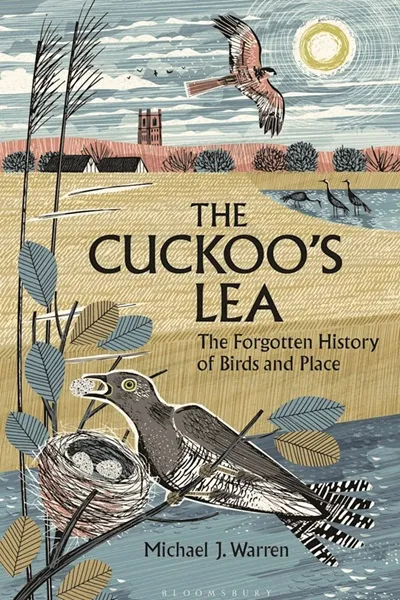

The Cuckoo’s Lea: The Forgotten History of Birds and Place

Author: Michael J. Warren

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, London

Published: 2025

In this book, author Michael Warren takes us on a journey across England (and a bit of Wales) and through time to explore the connection between English place names and birds. Especially interesting are those less obvious connections. It is not a difficult leap to see how Hawkhurst derives its name but the derivation of Yaxley (the Cuckoo’s Lea in the title) or Wroxton is fascinating. This book is far more than a simple gazetteer of ornithological toponomy though. The author visits the places and traces the old haunts of the birds, in many places sadly gone and replaced with industrial estates and as he poignantly puts it “litter-leaks”. The author’s skill is bringing the ghosts of the past to life so the reader can vividly picture the great fen before it was drained or medieval villages now completely wiped from the map. As well as the places, the author goes in search of the birds themselves, from Swallows and corvid roosts to more challenging species like Goshawk and brings these encounters to life with words that will resonate with birders. I was left with a sense that the place names explored in the book celebrated the natural world. In contrast, today’s ‘Skylark Ways’ and ‘Bunting Roads’, found in modern housing estates, feel like a hollow tribute - the developers’ ironic nods to the very wildlife their projects have displaced. The pace of the book occasionally lags, and some of the quoted Old English passages may challenge modern readers. However, for anyone interested in England’s natural and geographical history, this book is a rewarding and enriching read. Lastly, congratulations to artist Matt Johnson on his exquisite cover which really complements the spirit of the words within.

The Rarity Garden: The Great White Cape of Flamborough

Author: Richard Baines

Publisher: Yorkshire Coast Nature

Published: 2025

Barely a week goes by without another book appearing on the shelves which delves deep into the personal way that nature, in one way or another, has impacted on the writer’s life. Often self-reflective and equally self-reverential, there’s clearly a market for this type of writing.