Treecreeper

Introduction

Creeping up the bark of a tree in search of food, the Treecreeper's cryptic brown, white and yellow-gold plumage gives it the perfect camouflage.

Treecreepers need mature trees in which to search the bark's nooks, crannies and fissures for invertebrate food. They begin searching for food low down on a tree, working their way up before fluttering back down to the lower part of a nearby tree and completing the exercise over again.

Treecreepers are resident in Britain & Ireland and as a small bird, can suffer during harsh winters, resulting in population fluctuations. They are found throughout Britain & Ireland, except for the highest peaks and some of the more remote Scottish islands.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

#BirdSongBasics: Goldcrest and Treecreeper

Songs and Calls

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

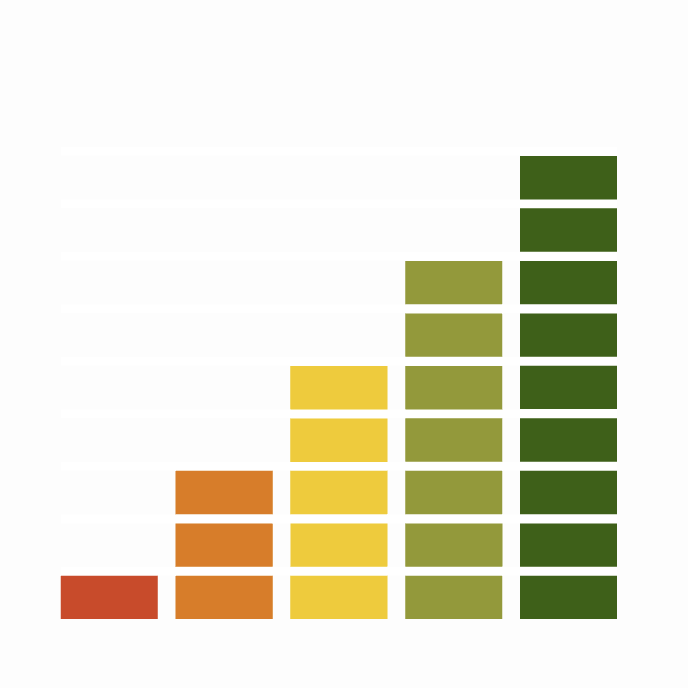

Population Change

The UK Treecreeper population peaked in the mid 1970s, but has been roughly stable since about 1980. Numbers across Europe have been broadly stable since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

During 2007–11

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Treecreeper overall range size has reduced by only 5% but this conceals noticeable losses in southwest England, eastern England and southwest Ireland which are partially offset by gains in Scotland and northwest Ireland. The latter may result from the creation and maturation of new woodland.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

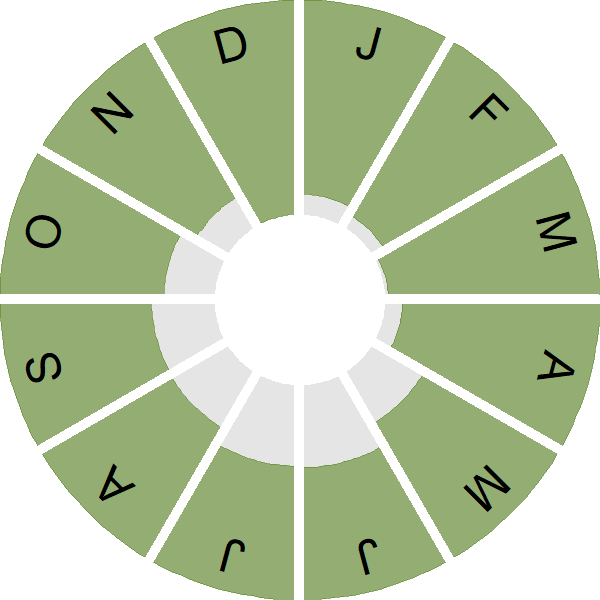

Seasonality

Treecreeper is recorded throughout the year.

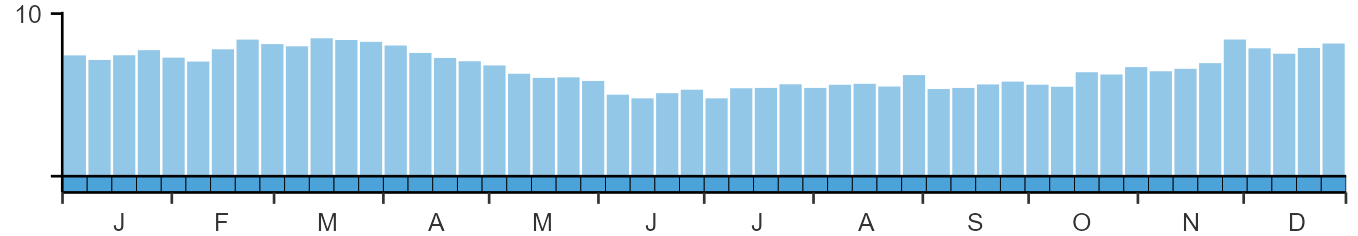

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

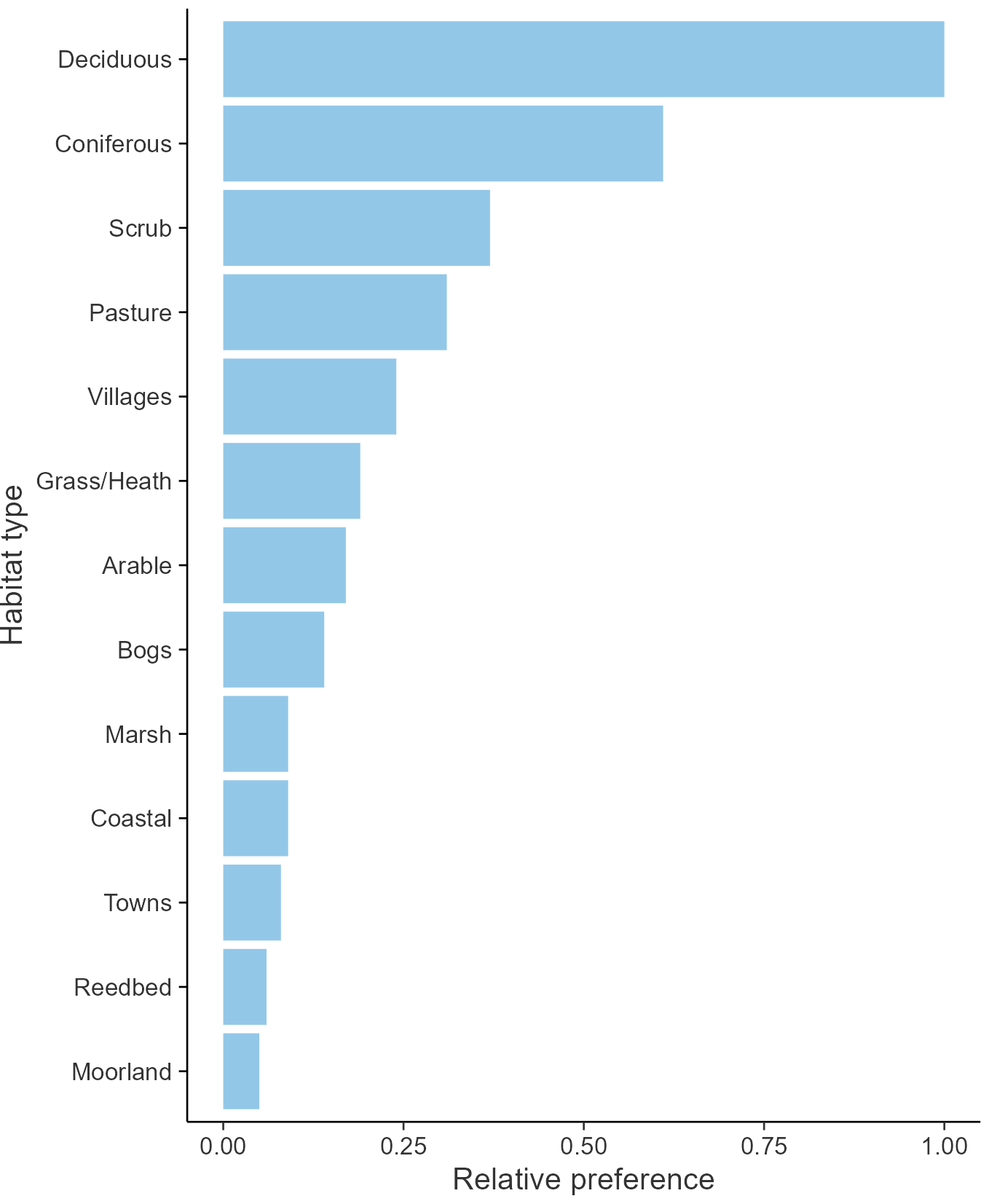

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Certhiidae

- Scientific name: Certhia familiaris

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: TC

- BTO 5-letter code: TREEC

- Euring code number: 14860

Alternate species names

- Catalan: raspinell pirinenc

- Czech: šoupálek dlouhoprstý

- Danish: Træløber

- Dutch: Taigaboomkruiper

- Estonian: porr

- Finnish: puukiipijä

- French: Grimpereau des bois

- Gaelic: Snàgair

- German: Waldbaumläufer

- Hungarian: hegyi fakusz

- Icelandic: Skógfeti

- Irish: Snag

- Italian: Rampichino alpestre

- Latvian: mizložna

- Lithuanian: eurazinis liputis

- Norwegian: Trekryper

- Polish: pelzacz lesny

- Portuguese: trepadeira-do-norte

- Slovak: kôrovník dlhoprstý

- Slovenian: dolgoprsti plezalcek

- Spanish: Agateador euroasiático

- Swedish: trädkrypare

- Welsh: Dringwr Bach

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The causes of change are unclear although changes to winter weather may have affected survival rates.

Further information on causes of change

Intensive study has shown that Treecreeper numbers and survival rates are reduced by wet winter weather (Peach et al. 1995b). The influence of cold weather is also evident in the low start to the index, following the severe winter of 1962/63, and the trough around 1980. Productivity, calculated using CES data, shows fluctuations since the 1980s. Nest failure rates at the egg stage fell in the 1970s and 1980s but has subsequently increased, and the number of fledglings per breeding attempt shows the opposite pattern and is now slightly lower than in the late 1960s. The trend towards earlier laying can be partly explained by recent climate change (Crick & Sparks 1999).

Information about conservation actions

The population of this species has increased consistently since the 1970s and it has expanded its range northwards, hence it is not a species of concern and no conservation actions are currently required.

Conservation actions benefiting other woodland species may also help Nuthatch. Habitat fragmentation may prevent Nuthatches from finding new sites (Verboom et al. 1991; Bellamy et al. 1998; van Langevelde 2008), and the provision of more frequent suitable patches of woodland across the landscape may therefore enable further colonisation and range expansion. Fragmentation may explain why numbers are relatively low and there are gaps in distribution in eastern England (Bellamy et al. 1998).

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).