Swift

Introduction

Swift is the long-distance migrant most associated with people, as it chooses to nest amongst our urban dwellings.

We await the return of Swifts to Britain and Ireland in early May and they are given the accolade of bringing the summer with them. Written about in poetry and prose, the dark scythe-winged silhouettes of Swifts wheeling about in a blue sky are often accompanied by their screaming calls.

Although widespread across much of Britain & Ireland, Breeding Bird Survey data have documented a significant decline in their populations. The reasons for these losses are likely to include poor summer weather, a decline in their insect food and continued loss of suitable nesting sites.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Hirundines & Swift

GBW: Swift, Swallow and House Martin

Songs and Calls

Call:

Flight call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Swifts were not monitored before the inception of the BBS. Their monitoring is complicated by the difficulty of finding occupied nests, by the weather-dependent and sometimes extraordinary distances from the nest at which breeding adults may forage, and by the often substantial midsummer influx of non-breeding individuals to the vicinity of breeding colonies. Since Swifts do not normally begin breeding until they are four years old, non-breeding numbers can be large. BBS results indicate that steep declines have occurred in England, Scotland and Wales since 1995. Many Swifts seen on BBS visits will not necessarily be nesting nearby, however, and the relationship between BBS transect counts and nesting numbers has not yet been investigated. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that decrease has been widespread, with some limited increases in parts of Wales and western Britain. On the strength of the BBS decline, Swift was moved from the green to the amber list of conservation concern in 2009 (Eaton et al. 2009) and then to the red list in 2021. A moderate decrease has been recorded in the Republic of Ireland since 1998 (Crowe 2012). Numbers across Europe have been broadly stable since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a).

Distribution

Swifts have a broad breeding distribution, with higher densities in warm, dry areas such as East Anglia, and lower densities in northern and western regions. In Britain & Ireland they nest almost exclusively in buildings and distribution and abundance maps show a close match to the built environment, with concentrations in towns and cities.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

In Britain the overall number of occupied 10-km squares has shown little change, but in Ireland there has been a 26% range contraction since the 1970s.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

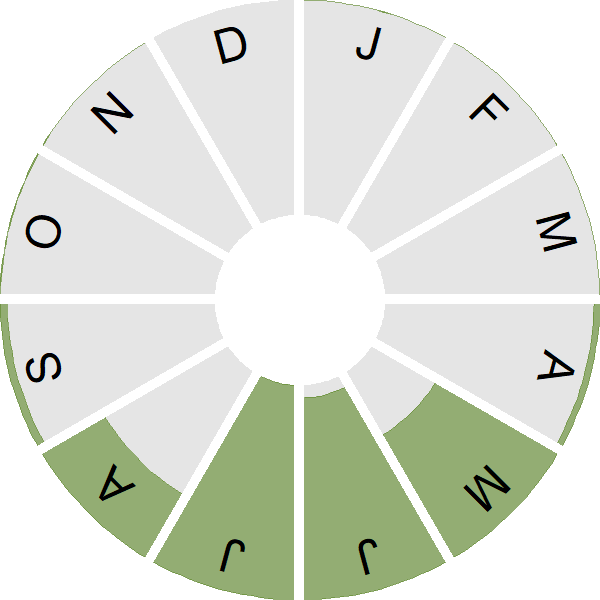

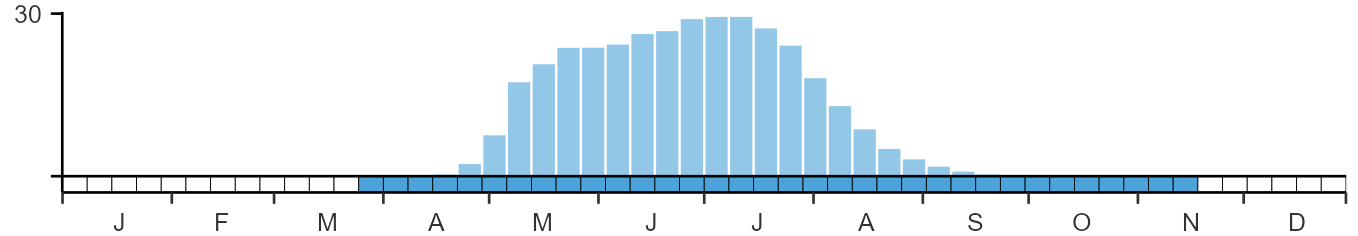

Seasonality

Swifts are summer visitors, arriving from late April with birds gradually departing from mid July; most birds usually departed by mid September but odd birds can appear even as late as November.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Apodiformes

- Family: Apodidae

- Scientific name: Apus apus

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: SI

- BTO 5-letter code: SWIFT

- Euring code number: 7950

Alternate species names

- Catalan: falciot negre

- Czech: rorýs obecný

- Danish: Mursejler

- Dutch: Gierzwaluw

- Estonian: piiritaja e. piirpääsuke

- Finnish: tervapääsky

- French: Martinet noir

- Gaelic: Gobhlan-mòr

- German: Mauersegler

- Hungarian: sarlósfecske

- Icelandic: Múrsvölungur

- Irish: Gabhlán Gaoithe

- Italian: Rondone comune

- Latvian: svire

- Lithuanian: juodasis ciurlys

- Norwegian: Tårnseiler

- Polish: jerzyk (zwyczajny)

- Portuguese: andorinhão-preto

- Slovak: dáždovník obycajný

- Slovenian: hudournik

- Spanish: Vencejo común

- Swedish: tornseglare

- Welsh: Gwennol Ddu

- English folkname(s): Devil Bird, Martlett

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The causes of the decline are unclear, although a recent analysis of BTO monitoring data (Finch et al. 2023) suggests that changes in juvenile (but not adult) survival are the most likely driver of the decline.

Further information on causes of change

Analysis of phenological change suggests that Swifts both arrive and depart in the UK earlier than in the 1960s, with the length of stay consequently remaining unchanged (Newson et al. 2016). Low juvenile survival appeared to be associated with poor weather conditions (Finch et al. 2023), implying a reduction in availability of aerial insects was causing additional mortality. Modern building design and refurbishment of old buildings are likely also have contributed to the decline by depriving Swifts of nest sites, but the complications in monitoring trends and nests (as described in the Status Summary) make it difficult to confirm the primary drivers of change.

Information about conservation actions

This species is difficult to monitor and hence the main drivers of the decline are uncertain. Given confirming the cause of decline is challenging and likely to remain so for some time, it would be prudent to take some precautionary actions whilst research is ongoing.Provision of additional nesting space to counter any reductions in availability of nest sites as a result of modern building designs and refurbishment of older buildings, either in the form of Swift nestboxes and Swift bricks which can be integrated into new buildings and renovations, as supported by Action for Swifts, Swift Conservationand similar organisations, are a relatively straightforward and inexpensive conservation action which can be taken by local groups and individuals, and can also be incorporated into wider development planning. Swifts are known to use these artificial nests (e.g. Schaub et al.2015). The availability of nest sites could also be increased on a wider scale by implementing policies or regulations which encourage or legislate the provision of nest boxes or Swift bricks on new buildings. Swift Towers are another option which have been used in Europe. Further information and advice about providing boxes and attracting Swifts to them is available on the Swift Conservationwebsite.

Swifts can forage over an extremely wide area during the breeding season, so other conservation actions such as habitat management in the vicinity of nest sites (to attempt to increase the availability of prey) are unlikely to be successful, unless they can be undertaken on a wider landscape scale. Whilst actions to increase levels of invertebrates across the wider countryside may benefit Swifts, further research is required, both to confirm whether changes to invertebrate abundance might be a cause of the Swift decline, and if so to identify the habitats which will provide the optimal requirements for foraging Swifts.

Publications (7)

Spatial variation in spring arrival patterns of Afro-Palearctic bird migration across Europe

Author:

Published: 2024

The timing of migrant birds’ arrival on the breeding grounds, or spring arrival, can affect their survival and breeding success. The optimal time for spring arrival involves trade-offs between various factors, including the availability of food and suitable breeding habitat, and the risks of severe weather. Due to climate change, the timing of spring emergence has advanced for many plants and insects which affects the timing of maximum food availability for migratory birds in turn. The degree to which different bird species can adapt to this varies. Understanding the factors that influence spring arrival in different species can help us to predict how they may respond to future changes in climate. This study looked at the variation across space in spring arrival time to Europe for 30 species of birds which winter in Africa. It used citizen science data from EuroBirdPortal, which collates casual birdwatching observations from 31 different European countries, including those submitted via BirdTrack. Using these data, the start, end and duration of spring migration was calculated at a 400 km resolution. The research identified patterns in arrival timing between groups of species, and tested whether these were linked to species traits: foraging strategy, weight, wintering location and length of breeding season. Lastly, it investigated how arrival timing was linked to temperature. The results showed that it takes 1.6 days on average for the leading migratory front to move northwards by 100 km (range: 0.6–2.5 days). The birds’ movements broadly tracked vegetation emergence in spring. Arrival timing could be split into two major groupings; species that arrived earlier and least synchronously, in colder temperatures and progressed slowly northward, and species that arrived later, most synchronously and in warmer temperatures, and advanced quickly through Europe. The slow progress of the early-arriving species suggests that temperature limits their northward advance. This group included aerial Insectivores (e.g. Swallow and Swift) and species that winter north of the Sahel (e.g. Chiffchaff and Blackcap). For the late-arriving species, which included species wintering further south, and heavier species (e.g. Red-backed shrike and Golden Oriole), they may need to wait until the wet season in Africa progresses enough for food to be available to them south of the Sahara before they can make the desert crossing. The research demonstrates that thanks to advances in citizen science, it is now possible to study arrival timing at a relatively fine scale across continents for a wide range of species, enabling a much fuller understanding of year-round variation between and within species, the associated trade-offs, and the pressures that species face. This knowledge can help mitigate threats to migrant species. For example, the dates of the start of spring migration could by used by each European country to inform hunting legislation. The approaches used in this work could be applied to other taxa where data are sufficient.

02.05.24

Papers

Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4: the population status of birds in Wales

Author:

Published: 2022

The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List, with 91 on the Amber List and just 69 - less than a third of the total number of species - on the Green List. The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales comes 20 years after the first, when the Red List was less than half the length it is today. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List in Wales, with 91 on the Amber List and 69 on the Green List. The Birds of Conservation Concern in Wales report assesses the status of each species against a set of objective criteria. Data sources include the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey and the BTO/RSPB/JNCC Wetland Bird Survey, as well as Bird Atlases and other BTO-led monitoring schemes and citizen science initiatives. These are used to quantify the changing status of the species’ Welsh population. The UK, European and global conservation status of the species is also considered, placing the Welsh population into a wider context. The Red ListSwift, Greenfinch and Rook – familiar breeding species in steep decline across the UK – are among the new additions to the Welsh Red List, which now also includes Purple Sandpiper, on account of a rapidly shrinking Welsh wintering population, and Leach’s Petrel, an enigmatic seabird in decline across its global range. These species now sit alongside well-known conservation priorities, such as Curlew, Hen Harrier and Turtle Dove as birds at risk of being lost from Wales for good. Uplands and woodlands Many of the species on the Red List are found in upland and farmland habitats. Starling, Tree Sparrow, Yellow Wagtail and Yellowhammer can no longer be found in much of Wales, while iconic species of mountain and moorland, such as Ring Ouzel, Merlin and Black Grouse, remain in serious trouble. Wales is well known for its populations of woodland birds; however, many of these – including Lesser Spotted Woodpecker, Willow Warbler and Spotted Flycatcher – also feature on the Red List. Goldcrest, which has seen its Welsh population shrink alarmingly in recent decades, is another new addition. On the coast The assessment for Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4 took place before the impacts of avian influenza could be taken into account. Breeding seabird species have been struggling in Wales for many years, however, and most were already of conservation concern before the outbreak of this disease. Kittiwake, Puffin, Black-headed Gull, and Common, Arctic and Sandwich Tern remain on the Red List. Wales holds internationally significant numbers of breeding seabirds, making the decline of these colonies a global concern. The Amber ListDeclines in Wheatear, Garden Warbler and House Martin - all migrants which breed in Europe and winter in sub-Saharan Africa - mean these species have moved from the Green List to the Amber List. Many other ‘Afro-Palearctic' migrant species are also in decline, but the potential reasons for this, such as habitat loss and reduced availability of invertebrate prey, are not well understood. Closer to home, the declines in the Welsh Chaffinch population, linked to the disease trichomonosis, have seen the species Amber-listed. A number of other species have been placed on the Amber List because of the wider importance of their Welsh populations, which in each case make up more than half the UK total. Wales is home to more than three-quarters of the UK’s Choughs, for example, so recent declines are cause for concern. The nation’s breeding populations of Manx Shearwater, Pied Flycatcher, Goshawk and Hawfinch also account for more than half the UK total, as does its wintering population of Spotted Redshank. It’s not all bad news, though: some species now on the Amber List have moved up from the Red List, indicating some positive change in their population trends. These include Common Sandpiper, Great Black-backed Gull, Bullfinch, Goldcrest and Pied Flycatcher. The Green ListWhile the report contains much cause for alarm, several conservation success stories shine through. Red Kite was almost lost as a British bird during the first half of the 20th century, when only a handful of pairs remained in remote Welsh valleys. Since then, a sustained conservation effort has brought the species back from the brink. Wales is now home to more than 2,500 pairs of Red Kite and the species has now been moved to the Green List, reflecting this incredible change in fortunes. Song Thrush, Reed Bunting, Long-tailed Tit, Redwing and Kingfisher are among the other species to have gone Green, providing much-needed hope that things can go up as well as down.

06.12.22

Reports Birds of Conservation Concern

Demography of Common Swifts Apus apus breeding in the UK associated with local weather but not aphid abundance

Author:

Published: 2022

Data from the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Birds Survey reveal that breeding Swift populations in the UK are in decline. Both reductions in the availability of invertebrate prey and the loss of nesting sites have been suggested as possible reasons, but the ultimate drivers of this decline are poorly understood. Can we improve our understanding of Swift decline by bringing together the information collected by bird ringers and nest recorders alongside data on insect availability and weather?

03.11.22

Papers

A 30,000-km journey by Apus apus pekinensis tracks arid lands between northern China and south-western Africa

Author:

Published: 2022

The Swift is widely distributed with a cross-continental breeding range spanning Europe and large parts of Asia and north Africa. Until recently, Swift migration research has focused on populations which breed in Europe and north-western Africa (the apus subspecies), leaving the migration of birds breeding throughout Asia (the pekinensis subspecies) shrouded in mystery.

29.06.22

Papers

The status of our bird populations: the fifth Birds of Conservation Concern in the United Kingdom, Channel Islands and Isle of Man and second IUCN Red List assessment of extinction risk for Great Britain

Author:

Published: 2021

Commonly referred to as the UK Red List for birds, this is the fifth review of the status of birds in the UK, Channel Islands and Isle of Man, published in December 2021 as Birds of Conservation Concern 5 (BOCC5). This updates the last assessment in 2015. Using standardised criteria, experts from a range of bird NGOs, including BTO, assessed 245 species with breeding, passage or wintering populations in the UK and assigned each to the Red, Amber or Green Lists of conservation concern. The same group of experts undertook a parallel exercise to assess the extinction risk of all bird species for Great Britain (the geographical area at which all other taxa are assessed) using the criteria and protocols established globally by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). This resulted in the assessment of 235 regularly occurring species (breeding or wintering or both), the total number assessed differing slightly from BOCC5 due to different rules on the inclusion of scarce breeders and colonisation patterns. The results of this second IUCN assessment (IUCN2) are provided in the same paper as BOCC5. Increasingly at risk This update shows that the UK’s bird species are increasingly at risk, with the Red List growing from 67 to 70. Eleven species were Red-listed for the first time, six due to worsening declines in breeding populations (Greenfinch, Swift, House Martin, Ptarmigan, Purple Sandpiper and Montagu’s Harrier), four due to worsening declines in non-breeding wintering populations (Bewick’s Swan, Goldeneye, Smew and Dunlin) and one (Leach’s Storm-petrel) because it is assessed according to IUCN criteria as Globally Vulnerable, and due to evidence of severe declines since 2000 based on new surveys on St Kilda, which holds more than 90% of the UK’s populations. The evidence for the changes in the other species come from the UK’s key monitoring schemes such as BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) for terrestrial birds, the BTO/RSPB/JNCC Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS) for wintering populations and the Rare Breeding Bird Panel (RBBP) for scarce breeding species such as Purple Sandpiper. The IUCN assessment resulted in 108 (46%) of regularly occurring species being assessed as threatened with extinction in Great Britain, meaning that their population status was classed as Critically Endangered, Endangered, or Vulnerable, as opposed to Near Threatened or of Least Concern. Of those 108 species, 21 were considered Critically Endangered, 41 Endangered and 46 Vulnerable. There is considerable overlap between the lists but unlike the Red List in BOCC5, IUCN2 highlights the vulnerability of some stable but small and hence vulnerable populations as well as declines in species over much shorter recent time periods, as seen for Chaffinch and Swallow.

01.12.21

Reports Birds of Conservation Concern

Evolution of chain migration in an aerial insectivorous bird, the Common Swift Apus apus

Author:

Published: 2020

The highly aerial Common Swift Apus apus, which spends the non‐breeding period on the wing, has been found to exhibit a rarely‐found chain migration pattern.

04.09.20

Papers

Identification of putative wintering areas and ecological determinants of population dynamics of Common House-Martin Delichon urbicum and Common Swift Apus apus breeding in Northern Italy

Author:

Published: 2011

To identify the causes of population decline in migratory birds, researchers must determine the relative influence of environmental changes on population dynamics while the birds are on breeding grounds, wintering grounds, and en route between the two. This is problematic when the wintering areas of specific populations are unknown. Here, we first identified the putative wintering areas of Common House-Martin (Delichon urbicum) and Common Swift (Apus apus) populations breeding in northern Italy as those areas, within the wintering ranges of these species, where the winter Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), which may affect winter survival, best predicted annual variation in population indices observed in the breeding grounds in 1992–2009. In these analyses, we controlled for the potentially confounding effects of rainfall in the breeding grounds during the previous year, which may affect reproductive success; the North Atlantic Oscillation Index (NAO), which may account for climatic conditions faced by birds during migration; and the linear and squared term of year, which account for nonlinear population trends. The areas thus identified ranged from Guinea to Nigeria for the Common House-Martin, and were located in southern Ghana for the Common Swift. We then regressed annual population indices on mean NDVI values in the putative wintering areas and on the other variables, and used Bayesian model averaging (BMA) and hierarchical partitioning (HP) of variance to assess their relative contribution to population dynamics. We re-ran all the analyses using NDVI values at different spatial scales, and consistently found that our population of Common House-Martin was primarily affected by spring rainfall (43%–47.7% explained variance) and NDVI (24%–26.9%), while the Common Swift population was primarily affected by the NDVI (22.7%–34.8%). Although these results must be further validated, currently they are the only hypotheses about the wintering grounds of the Italian populations of these species, as no Common House-Martin and Common Swift ringed in Italy have been recovered in their wintering ranges. To identify the causes of population decline in migratory birds, researchers must determine the relative influence of environmental changes on population dynamics while the birds are on breeding grounds, wintering grounds, and en route between the two. This is problematic when the wintering areas of specific populations are unknown. Here, we first identified the putative wintering areas of Common House-Martin (Delichon urbicum) and Common Swift (Apus apus) populations breeding in northern Italy as those areas, within the wintering ranges of these species, where the winter Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), which may affect winter survival, best predicted annual variation in population indices observed in the breeding grounds in 1992–2009. In these analyses, we controlled for the potentially confounding effects of rainfall in the breeding grounds during the previous year, which may affect reproductive success; the North Atlantic Oscillation Index (NAO), which may account for climatic conditions faced by birds during migration; and the linear and squared term of year, which account for nonlinear population trends. The areas thus identified ranged from Guinea to Nigeria for the Common House-Martin, and were located in southern Ghana for the Common Swift. We then regressed annual population indices on mean NDVI values in the putative wintering areas and on the other variables, and used Bayesian model averaging (BMA) and hierarchical partitioning (HP) of variance to assess their relative contribution to population dynamics. We re-ran all the analyses using NDVI values at different spatial scales, and consistently found that our population of Common House-Martin was primarily affected by spring rainfall (43%–47.7% explained variance) and NDVI (24%–26.9%), while the Common Swift population was primarily affected by the NDVI (22.7%–34.8%). Although these results must be further validated, currently they are the only hypotheses about the wintering grounds of the Italian populations of these species, as no Common House-Martin and Common Swift ringed in Italy have been recovered in their wintering ranges.

01.01.11

Papers

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).