Swallow

Introduction

The sight of an early spring Swallow with its long, forked tail, red throat and white belly signals that summer is not far away.

A long-distance migrant, many of our Swallows spend the winter months in South Africa. The first Swallows begin to arrive in the UK during March and stay here into October. In recent years a small number of birds have attempted, in some years successfully, to overwinter in the UK.

The Swallow can be found across Britain & Ireland and can be seen flying at speed just inches above its favoured grassland feeding habitat as it snatches its insect prey. UK Swallow have fluctuated sharply in recent decades, with declines seen in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland since about 2010.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Hirundines & Swift

GBW: Swift, Swallow and House Martin

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Alarm call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Swallow was originally amber listed partly on the strength of a decline on CBC plots in the early 1980s, but later modelling of UK population change from CBC gave evidence of fluctuations but not of long-term decline (Robinson et al. 2003). Nevertheless, the species continued to qualify for amber listing through its 'depleted' status across the European continent (BirdLife International 2004). Following further review of its status in Europe, the species was moved to the UK green list in 2015 (Eaton et al. 2015). The trend has been broadly stable across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

BBS data suggest shallow increases occurred in England, Scotland and Wales from 1995 until around 2010. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09, however, indicates that decreases had occurred during that period in Northern Ireland and in eastern coastal regions of Britain, with the strongest increases in western Britain. More recent BBS records indicate that declines have occurred in all four UK countries over the last ten years, reversing the earlier increases.

Distribution

Recorded breeding in 95% of 10-km squares, the Swallow has the most extensive distribution of any summer migrant in Britain & Ireland. It is absent only from a few areas of northern Scotland and from central London. It occurs at high densities throughout Ireland.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Overall range size has changed little over the course of the atlases, although gains point to a small northward expansion.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

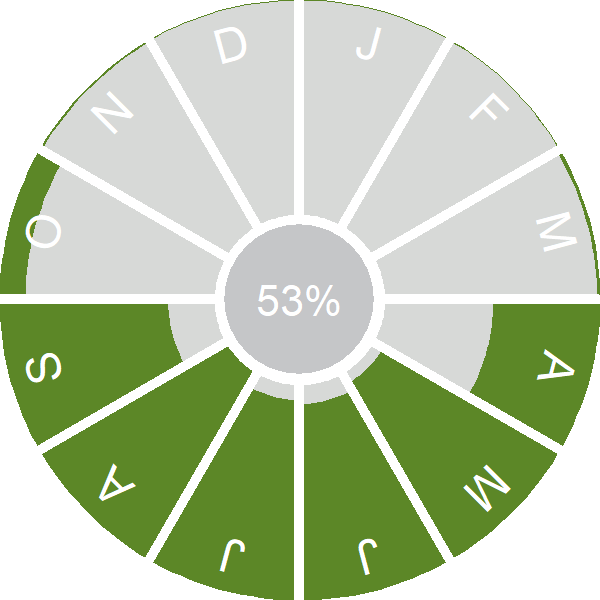

Seasonality

Swallows usually arrive from April onwards with birds beginning to depart in September; stragglers may be present into October.

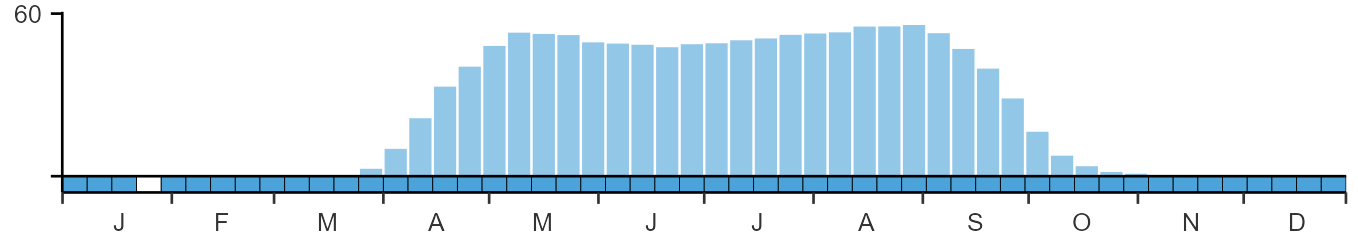

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Migrant arrival timing

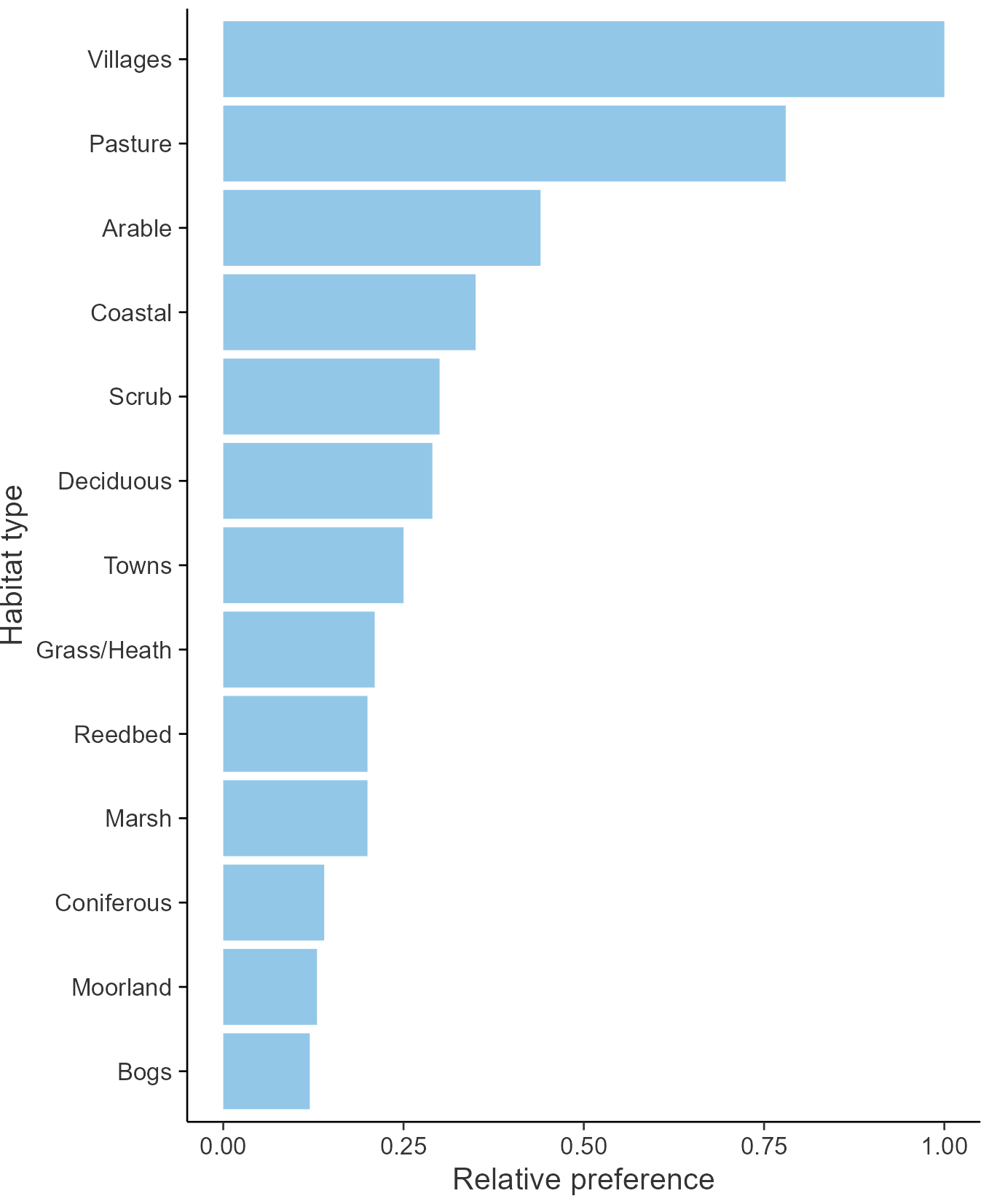

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Hirundinidae

- Scientific name: Hirundo rustica

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: SL

- BTO 5-letter code: SWALL

- Euring code number: 9920

Alternate species names

- Catalan: oreneta comuna

- Czech: vlaštovka obecná

- Danish: Landsvale

- Dutch: Boerenzwaluw

- Estonian: suitsupääsuke

- Finnish: haarapääsky

- French: Hirondelle rustique

- Gaelic: Gobhlan-gaoithe

- German: Rauchschwalbe

- Hungarian: füsti fecske

- Icelandic: Landsvala

- Irish: Fáinleog

- Italian: Rondine

- Latvian: bezdeliga

- Lithuanian: šelmenine kregžde

- Norwegian: Låvesvale

- Polish: dymówka

- Portuguese: andorinha-de-bando / andorinha-das-chaminés

- Slovak: lastovicka obycajná

- Slovenian: kmecka lastovka

- Spanish: Golondrina común

- Swedish: ladusvala

- Welsh: Gwennol

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The reasons for change are currently unclear. Although agricultural intensification is likely to be a primary driver, over-winter survival and changes in habitat on the breeding grounds may both be having an effect.

Further information on causes of change

Population fluctuations are most strongly related to variable levels of survival (Robinson et al. 2014), most likely on their wintering grounds (Baillie & Peach 1992). More particularly, annual population change has been shown to be correlated with rainfall in the western Sahel prior to the birds' spring passage through West Africa, but with neither cattle numbers nor nest-site availability in the UK (Robinson et al. 2003). Annual survival rates from RAS sites in the UK for 1998-2004 were correlated positively with mean monthly rainfall during the early austral summer in southern Africa (Robinson et al. 2008). A review of research into threats to adult survival of several hirundine species, including Swallow, identified weather conditions throughout the annual cycle as a key threat (Imlay & Leonard 2019). There is also evidence suggesting that weather conditions experienced by Swallows during winter may have carry over effects which could affect breeding productivity the following summer (Saino et al. 2012).

It is likely that, in eastern parts of the UK, the loss of livestock farming and grazed grassland, together with arable intensification, has caused the Swallow population to decline, while an increase in the area of pasture in the west and north has promoted a population increase which apparently has more than compensated for declines elsewhere (Evans & Robinson 2004). A link between regional changes in the availability of preferred feeding habitats and the regional patterns of UK population change again suggests that habitat change on the breeding grounds may explain population trend, at least partly (Henderson et al. 2007). Brood size increased up to the late 1980s, however current data show no difference in brood size compared to the late 1960s, while nest losses have increased and the number of fledglings per breeding attempt shows no trend. A Danish study over 22 years found that the number of nesting pairs and the rate at which birds made feeding visits to nests declined in parallel with declines in insect abundance (Moller 2019); however numbers of fledglings were not counted by this study. Further evidence is therefore needed to confirm whether agricultural intensification and changes in insect abundance may have been sufficient to directly affect nest productivity and hence cause population changes at local and wider scales.

Climatic warming is leading to an earlier start to the breeding season for European Swallows, and analysis of phenological data has found that the arrival date in the UK has advanced, between the 1960s and 2000s, by 15 days (Newson et al. 2016), with the laying date also advancing (see above). Facey et al. (2020) found that nestling mass was negatively correlated with temperature, although the relationship with other weather conditions was complex and fledgling body mass was less sensitive to weather, hence the lower nestling body mass does not necessarily have any subsequent effect on juvenile survival and hence on population trends. However, Turner (2009) found that there has been increased chick mortality in hot, dry summers and reduced post-fledging survival because of poor conditions for birds migrating through North Africa. A study in eastern Germany also highlighted reduced breeding success despite earlier breeding, and suggested that a mismatch between local and large-scale climatic changes may mean that, for this species, earlier breeding was not sufficient in that region to respond to climate change (Grimm et al. 2015).

Information about conservation actions

The decline of the Swallow in some parts of the UK may relate to agricultural intensification and changes of land use. There is evidence from several studies in Europe, including one in the UK, that the retention of cattle for meat or dairy farming may improve breeding performance and colony size and buffer Swallow declines ( Moller 2001 ; Evans et al. 2007; Gruebler et al. 2010; Ambrosini et al. 2012; Sicurella et al. 2014), with the presence of manure heaps also important ( Gruebler et al. 2010), and the presence of greater numbers of hayfields within 200 m of the colony increasing colony size at farms without livestock (Sicurella et al. 2014).

Artificial nests have also been suggested as a possible conservation option. In a study in Denmark, artificial nests had a low predation rate which was similar to natural nests, and showed higher breeding productivity. The author speculated that this could be due to the saving of energy and time costs from nest construction ( Teglhoj et al. 2018).

Publications (4)

Spatial variation in spring arrival patterns of Afro-Palearctic bird migration across Europe

Author:

Published: 2024

The timing of migrant birds’ arrival on the breeding grounds, or spring arrival, can affect their survival and breeding success. The optimal time for spring arrival involves trade-offs between various factors, including the availability of food and suitable breeding habitat, and the risks of severe weather. Due to climate change, the timing of spring emergence has advanced for many plants and insects which affects the timing of maximum food availability for migratory birds in turn. The degree to which different bird species can adapt to this varies. Understanding the factors that influence spring arrival in different species can help us to predict how they may respond to future changes in climate. This study looked at the variation across space in spring arrival time to Europe for 30 species of birds which winter in Africa. It used citizen science data from EuroBirdPortal, which collates casual birdwatching observations from 31 different European countries, including those submitted via BirdTrack. Using these data, the start, end and duration of spring migration was calculated at a 400 km resolution. The research identified patterns in arrival timing between groups of species, and tested whether these were linked to species traits: foraging strategy, weight, wintering location and length of breeding season. Lastly, it investigated how arrival timing was linked to temperature. The results showed that it takes 1.6 days on average for the leading migratory front to move northwards by 100 km (range: 0.6–2.5 days). The birds’ movements broadly tracked vegetation emergence in spring. Arrival timing could be split into two major groupings; species that arrived earlier and least synchronously, in colder temperatures and progressed slowly northward, and species that arrived later, most synchronously and in warmer temperatures, and advanced quickly through Europe. The slow progress of the early-arriving species suggests that temperature limits their northward advance. This group included aerial Insectivores (e.g. Swallow and Swift) and species that winter north of the Sahel (e.g. Chiffchaff and Blackcap). For the late-arriving species, which included species wintering further south, and heavier species (e.g. Red-backed shrike and Golden Oriole), they may need to wait until the wet season in Africa progresses enough for food to be available to them south of the Sahara before they can make the desert crossing. The research demonstrates that thanks to advances in citizen science, it is now possible to study arrival timing at a relatively fine scale across continents for a wide range of species, enabling a much fuller understanding of year-round variation between and within species, the associated trade-offs, and the pressures that species face. This knowledge can help mitigate threats to migrant species. For example, the dates of the start of spring migration could by used by each European country to inform hunting legislation. The approaches used in this work could be applied to other taxa where data are sufficient.

02.05.24

Papers

The status of our bird populations: the fifth Birds of Conservation Concern in the United Kingdom, Channel Islands and Isle of Man and second IUCN Red List assessment of extinction risk for Great Britain

Author:

Published: 2021

Commonly referred to as the UK Red List for birds, this is the fifth review of the status of birds in the UK, Channel Islands and Isle of Man, published in December 2021 as Birds of Conservation Concern 5 (BOCC5). This updates the last assessment in 2015. Using standardised criteria, experts from a range of bird NGOs, including BTO, assessed 245 species with breeding, passage or wintering populations in the UK and assigned each to the Red, Amber or Green Lists of conservation concern. The same group of experts undertook a parallel exercise to assess the extinction risk of all bird species for Great Britain (the geographical area at which all other taxa are assessed) using the criteria and protocols established globally by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). This resulted in the assessment of 235 regularly occurring species (breeding or wintering or both), the total number assessed differing slightly from BOCC5 due to different rules on the inclusion of scarce breeders and colonisation patterns. The results of this second IUCN assessment (IUCN2) are provided in the same paper as BOCC5. Increasingly at risk This update shows that the UK’s bird species are increasingly at risk, with the Red List growing from 67 to 70. Eleven species were Red-listed for the first time, six due to worsening declines in breeding populations (Greenfinch, Swift, House Martin, Ptarmigan, Purple Sandpiper and Montagu’s Harrier), four due to worsening declines in non-breeding wintering populations (Bewick’s Swan, Goldeneye, Smew and Dunlin) and one (Leach’s Storm-petrel) because it is assessed according to IUCN criteria as Globally Vulnerable, and due to evidence of severe declines since 2000 based on new surveys on St Kilda, which holds more than 90% of the UK’s populations. The evidence for the changes in the other species come from the UK’s key monitoring schemes such as BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) for terrestrial birds, the BTO/RSPB/JNCC Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS) for wintering populations and the Rare Breeding Bird Panel (RBBP) for scarce breeding species such as Purple Sandpiper. The IUCN assessment resulted in 108 (46%) of regularly occurring species being assessed as threatened with extinction in Great Britain, meaning that their population status was classed as Critically Endangered, Endangered, or Vulnerable, as opposed to Near Threatened or of Least Concern. Of those 108 species, 21 were considered Critically Endangered, 41 Endangered and 46 Vulnerable. There is considerable overlap between the lists but unlike the Red List in BOCC5, IUCN2 highlights the vulnerability of some stable but small and hence vulnerable populations as well as declines in species over much shorter recent time periods, as seen for Chaffinch and Swallow.

01.12.21

Reports Birds of Conservation Concern

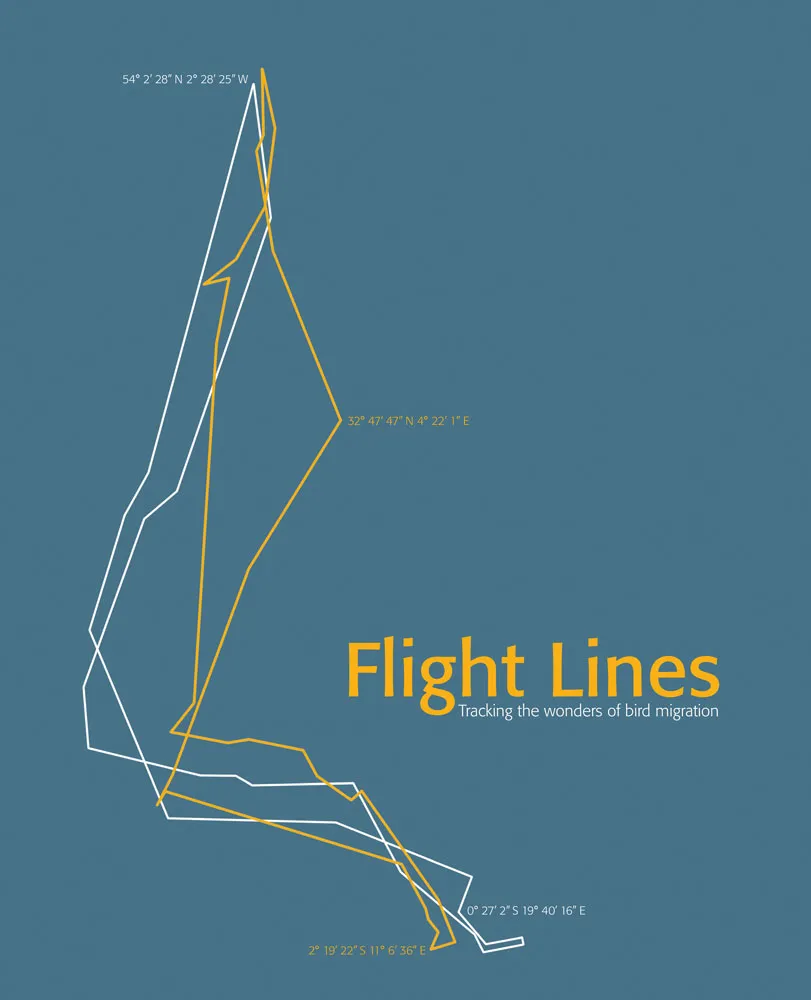

Flight Lines: Tracking the wonders of bird migration

Author:

Published: 2017

This stunning new book brings together the latest research findings, delivered through an accessible and engaging narrative by the BTO's Mike Toms, with the wonderful artwork generated through the BTO/SWLA Flight Lines project. If you have an interest in our summer migrants, then you'll welcome this fantastic opportunity to discover their stories through art and the written word. By pairing artists, storytellers and photojournalists with the researchers and volunteers studying our summer migrants, we are able to tell the stories of our migrant birds, and the work being done to secure a future for them. Includes artwork by SWLA member artists Carry Akroyd, Kim Atkinson, Federico Gemma, Richard Johnson, Szabolcs Kokay, Harriet Mead, Bruce Pearson, Greg Poole, Dafila Scott, Jane Smith, John Threlfall, Esther Tyson, Matt Underwood, Michael Warren, Darren Woodhead and others.

21.08.17

Books and guides Book

An assessment of the potential benefits of additional stratification of BBS squares by habitat and accessibility to enhance the monitoring of rare species and habitats.

Author:

Published: 2016

Every year, volunteers across the UK take part in the BTO/RSPB/JNCC Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), recording breeding birds in randomly selected 1-km squares (stratified regionally by observer availability) to robustly monitor population trends of some UK bird species. However, the chances of randomly selected squares containing rarer bird species and the habitats of interest that only cover a small proportion of the landscape are low, limiting our ability to monitor population changes. The work reported here examines options for increasing coverage of rare species and of assemblages occupying certain habitats of interest within the BBS framework, by including additional strata based on habitat type. It also assesses the benefits and risks of including an additional stratum based on accessibility to increase volunteer uptake in large regions with low observer density and many inaccessible areas. Volunteer recruitment is often difficult in these regions because randomly selected unmonitored BBS squares may require long drives, difficult walks and over-night camping.

23.03.16

BTO Research Reports

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).