Spotted Flycatcher

Introduction

More streaked than spotted, this small grey-brown, long-winged flycatcher is a dashing bird of woodland, parks and gardens.

The Spotted Flycatcher is amongst the last of our summer visitors to arrive, often not being seen until late April or even early May. It breeds throughout Britain & Ireland, apart from the very far north and west.

Spotted Flycatchers spend the winter months in Africa and BTO research has shown that some head as far south as Namibia, around 7,000 km from their breeding location. A host of summer migrants are experiencing declines in their breeding populations and the Spotted Flycatcher is one of these. It has been on the UK Red List since 1996.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Spotted Flycatchers have declined rapidly and consistently since the 1960s. It is among a suite of species that winter in the humid zone of West Africa and correspondingly are showing the strongest population declines among our migrant species (Ockendon et al. 2012, 2014).

The Repeat Woodland Bird Survey, however, using a set of CBC woodland and RSPB sites, detected a significant increase between the 1980s and 2003-04 in southwest England (Amar et al. 2006, Hewson et al. 2007), suggesting that change has not been uniform across Britain.

Gaps are already starting to appear in the 10-km distribution map, especially in urban areas and close to the east coast (Balmer et al. 2013). There has been a decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

Spotted Flycatchers have undergone a major population decline. At the time of the 2008–11 atlas they could still be found in a high proportion of 10-km squares, but these maps may now be out of date as declines have continued. Spotted Flycacther densities were generally greatest in the north and west of the range.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Up to 2008–11 range losses in Britain were relatively minor: the 10% range loss was concentrated in and around major conurbations. In Ireland there has been a more substantial 21% range contraction with major losses along the west coast. The atlas abundance change map showed declines in tetrad occupancy throughout most of England, Wales and eastern Scotland since the 1988–91 Breeding Atlas.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

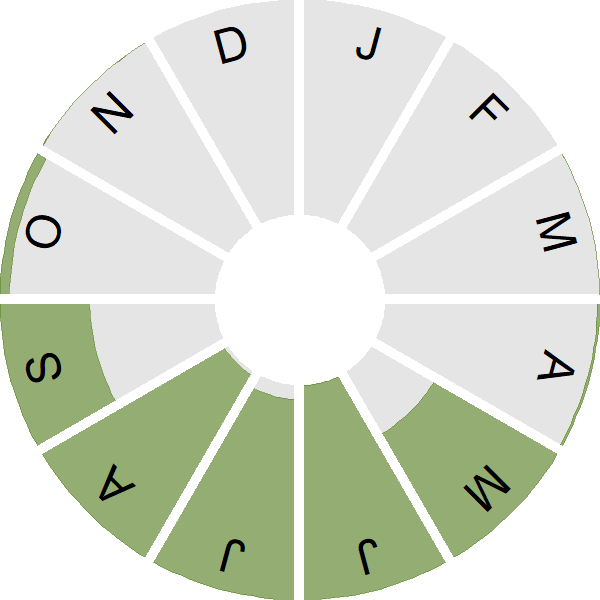

Seasonality

Spotted Flycatcher is one of our latest summer visitors, arriving through May and departing in September.

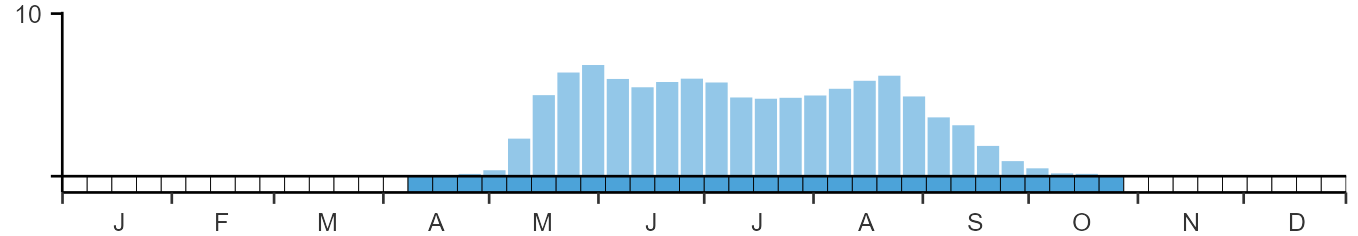

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Muscicapidae

- Scientific name: Muscicapa striata

- Authority: Pallas, 1764

- BTO 2-letter code: SF

- BTO 5-letter code: SPOFL

- Euring code number: 13350

Alternate species names

- Catalan: papamosques gris

- Czech: lejsek šedý

- Danish: Grå Fluesnapper

- Dutch: Grauwe Vliegenvanger

- Estonian: hall-kärbsenäpp

- Finnish: harmaasieppo

- French: Gobemouche gris

- Gaelic: Breacan-sgiobalt

- German: Grauschnäpper

- Hungarian: szürke légykapó

- Icelandic: Grágrípur

- Irish: Cuilire Liath

- Italian: Pigliamosche

- Latvian: pelekais muškerajs

- Lithuanian: pilkoji musinuke

- Norwegian: Gråfluesnapper

- Polish: mucholówka szara

- Portuguese: taralhão-cinzento

- Slovak: muchár sivý

- Slovenian: sivi muhar

- Spanish: Papamoscas gris

- Swedish: grå flugsnappare

- Welsh: Gwybedog Mannog

- English folkname(s): Beam Bird

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

Demographic modelling provides evidence that a decrease in the annual survival rates of birds in their first year may have driven the decline. The ecological causes of the decline are uncertain as good-quality, direct evidence is sparse.

Further information on causes of change

Nest failure rates show little overall change (with a marginal decrease in egg-stage failure offset by an increase at the chick stage) and the number of fledglings per breeding attempt shows no trend. Though samples are too small to continue presenting a trend, there was a decrease overall in the ratio of juveniles to adults in CES captures. However, demographic modelling shows that decreases in the annual survival rates of birds in their first year of life are more likely to have driven the population decline than breeding parameters (Freeman & Crick 2003, Stevens et al. 2007). This effect on survival may operate in the pre-migration period, during migration or in the wintering quarters. The number of adult Spotted Flycatchers caught at CES ringing sites was found to have declined drastically, providing further evidence that post-fledging and overwinter survival may be important factors in the population decline (Peach et al. 1998).

Evidence for the ecological causes of the decline is sparse. Fuller et al. (2005) hypothesise that declines in large flying insects that are food to the flycatcher, or conditions either on the wintering grounds or along migration routes may be involved. However, there is little detailed evidence to directly support any of these ideas.

Data from the Repeat Woodland Bird Survey (Amar et al. 2006) showed that Spotted Flycatchers were more likely to have declined at sites with very open or very closed foliage conditions. Smart et al. (2007) also suggest this. However, overall, Amar et al. (2006) did not find that changes in habitat were significant in explaining population declines for this species. Stevens et al. (2007) found that nests in gardens fledged twice as many chicks as those in either woodland or farmland. The proximate cause of lower success in farmland and woodland was higher nest predation rates. In a follow-up study using nest cameras, 17 out of 20 predation events were carried out by avian predators and 12 of these were by Jays (Stevens et al. 2008). In terms of nesting success, farmland and woodland appear to be suboptimal when compared with gardens, providing evidence of a problem on the breeding grounds for this species, at least in these two habitats (Stevens et al. 2007). However, the absence of any change in nest failure rates (as reported above) suggests that predation has not been the main driver of the overall decline.

In Leicestershire, Stoate & Szczur (2006) found that the removal of nest predators prompted an increase in Spotted Flycatcher breeding success, especially in woodland, where nest success was lower overall than in gardens. However, Carpenter et al. (2009) found no link between presence/absence, abundance and population change of the species and avian predator abundance.

Information about conservation actions

The ecological drivers of the long-term decline are uncertain, and although there is evidence that it may be linked to first-year survival it is still unclear whether this is occurring during the post-breeding period in the UK, or whilst the species are outside the UK during migration or on their wintering grounds. It is therefore uncertain whether conservation actions taken in the UK will have any significant effect on Spotted Flycatcher abundance.

In woodland, sites with intermediate foliage conditions (rather than very open or very closed foliage) seem to be preferred (see Causes of Change section, above). Nests in woodland or farmland are more likely to be predated than those in gardens (Stevens et al. 2007) and removal of nest predators can lead to localised improvements in breeding success, although there is no evidence that avian predator abundance has population level effects (see Causes of Change section).

Publications (3)

Role of freshwater availability and terrestrial land-cover change in the distribution of a declining, terrestrial, insectivorous bird

Author:

Published: 2026

The density of rivers is strongly associated with the persistence of the Spotted Flycatcher, a Red-listed migratory species in sharp decline in the UK. Protection and improvement of riverine habitats and understanding their benefits for terrestrial species should be a priority for conservation management.

14.01.26

Papers

Cross‑system transfer of fatty acids from aquatic insects supports terrestrial insectivore condition and reproductive success

Author:

Published: 2025

12.11.25

Papers

Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4: the population status of birds in Wales

Author:

Published: 2022

The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List, with 91 on the Amber List and just 69 - less than a third of the total number of species - on the Green List. The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales comes 20 years after the first, when the Red List was less than half the length it is today. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List in Wales, with 91 on the Amber List and 69 on the Green List. The Birds of Conservation Concern in Wales report assesses the status of each species against a set of objective criteria. Data sources include the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey and the BTO/RSPB/JNCC Wetland Bird Survey, as well as Bird Atlases and other BTO-led monitoring schemes and citizen science initiatives. These are used to quantify the changing status of the species’ Welsh population. The UK, European and global conservation status of the species is also considered, placing the Welsh population into a wider context. The Red ListSwift, Greenfinch and Rook – familiar breeding species in steep decline across the UK – are among the new additions to the Welsh Red List, which now also includes Purple Sandpiper, on account of a rapidly shrinking Welsh wintering population, and Leach’s Petrel, an enigmatic seabird in decline across its global range. These species now sit alongside well-known conservation priorities, such as Curlew, Hen Harrier and Turtle Dove as birds at risk of being lost from Wales for good. Uplands and woodlands Many of the species on the Red List are found in upland and farmland habitats. Starling, Tree Sparrow, Yellow Wagtail and Yellowhammer can no longer be found in much of Wales, while iconic species of mountain and moorland, such as Ring Ouzel, Merlin and Black Grouse, remain in serious trouble. Wales is well known for its populations of woodland birds; however, many of these – including Lesser Spotted Woodpecker, Willow Warbler and Spotted Flycatcher – also feature on the Red List. Goldcrest, which has seen its Welsh population shrink alarmingly in recent decades, is another new addition. On the coast The assessment for Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4 took place before the impacts of avian influenza could be taken into account. Breeding seabird species have been struggling in Wales for many years, however, and most were already of conservation concern before the outbreak of this disease. Kittiwake, Puffin, Black-headed Gull, and Common, Arctic and Sandwich Tern remain on the Red List. Wales holds internationally significant numbers of breeding seabirds, making the decline of these colonies a global concern. The Amber ListDeclines in Wheatear, Garden Warbler and House Martin - all migrants which breed in Europe and winter in sub-Saharan Africa - mean these species have moved from the Green List to the Amber List. Many other ‘Afro-Palearctic' migrant species are also in decline, but the potential reasons for this, such as habitat loss and reduced availability of invertebrate prey, are not well understood. Closer to home, the declines in the Welsh Chaffinch population, linked to the disease trichomonosis, have seen the species Amber-listed. A number of other species have been placed on the Amber List because of the wider importance of their Welsh populations, which in each case make up more than half the UK total. Wales is home to more than three-quarters of the UK’s Choughs, for example, so recent declines are cause for concern. The nation’s breeding populations of Manx Shearwater, Pied Flycatcher, Goshawk and Hawfinch also account for more than half the UK total, as does its wintering population of Spotted Redshank. It’s not all bad news, though: some species now on the Amber List have moved up from the Red List, indicating some positive change in their population trends. These include Common Sandpiper, Great Black-backed Gull, Bullfinch, Goldcrest and Pied Flycatcher. The Green ListWhile the report contains much cause for alarm, several conservation success stories shine through. Red Kite was almost lost as a British bird during the first half of the 20th century, when only a handful of pairs remained in remote Welsh valleys. Since then, a sustained conservation effort has brought the species back from the brink. Wales is now home to more than 2,500 pairs of Red Kite and the species has now been moved to the Green List, reflecting this incredible change in fortunes. Song Thrush, Reed Bunting, Long-tailed Tit, Redwing and Kingfisher are among the other species to have gone Green, providing much-needed hope that things can go up as well as down.

06.12.22

Reports Birds of Conservation Concern

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).