Reed Warbler

Introduction

The Reed Warbler is a bird of reedbeds, where its rhythmic song can be heard from April to September.

A recent colonist to southern Scotland, the Reed Warbler is largely confined to reedbeds and riverside reed fringes of England, Wales and eastern parts of the island of Ireland. The Reed Warbler is double brooded, laying two clutches of eggs during late spring and midsummer. It is a common host species of the Cuckoo.

UK Reed Warbler numbers increased in the latter part of the 20th century, stabilising in the early-2000s. Most Reed Warblers leave the Britain & Ireland by mid September to spend the winter in Africa, south of the Sahara Desert.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Warbler Identification Workshop Part 3: Reed and Sedge Warbler

Songs and Calls

Song:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

This species has an unusually clumped distribution, with very high breeding concentrations in Phragmites reedbeds, where numbers are very hard to census. CES, which has many sites in reedbeds, ought perhaps to be a better measure of population change than either CBC/BBS or WBS/WBBS, where the species is encountered mainly at low density or in linear habitats. Both CBC/BBS and WBS/WBBS show progressive strong increases. CES, however, shows a decline from 1983 until the early 1990s, followed by a partial recovery, and another more recent decline. Population increase, as indicated by the census work, accords with the remarkable range expansion the species has achieved since the 1960s, as recorded by atlas projects. West Wales, northwest and northeast England were colonised, as was the east coast of Ireland, between 1968-72 and 1988-91 (Gibbons et al. 1993), and the species is now regular as far north as the Tay reedbeds (Robertson 2003, Balmer et al. 2013). Numbers across Europe have been broadly stable since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

The majority of the Reed Warbler population in Britain still breeds to the south of South Yorkshire and Lancashire, although gradual northward and westward range expansion have been underway for several decades. The highest breeding densities are found in eastern England, particularly in the Fens where there are many Phragmites-dominated areas for breeding. Small numbers breed in Ireland.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

The Reed Warbler's British breeding range has expanded by 40% since the 1968–72 breeding atlas. Northward range expansion saw Reed Warblers breed in Scotland for the first time in 1987 in the large Tay reedbeds.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

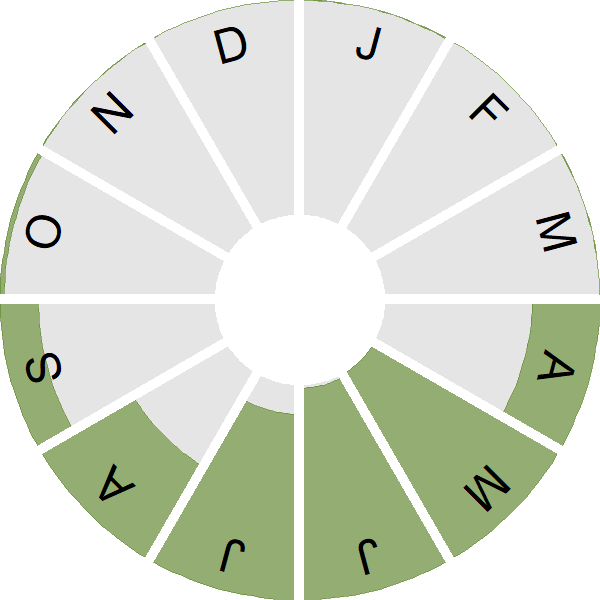

Reed Warbler is a summer visitor, arriving from mid April with autumn migration extending into early October.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

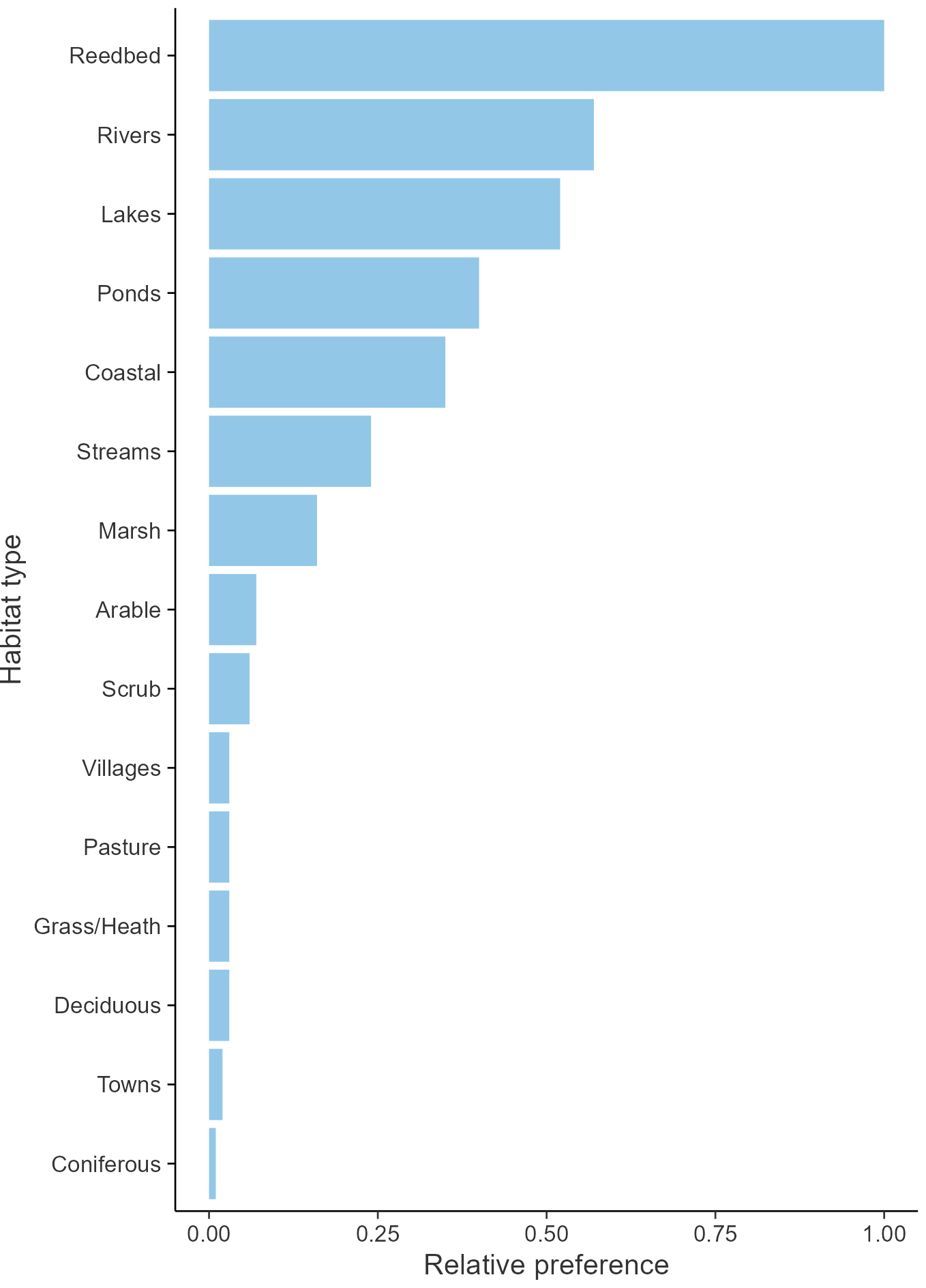

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Acrocephalidae

- Scientific name: Acrocephalus scirpaceus

- Authority: Hermann, 1804

- BTO 2-letter code: RW

- BTO 5-letter code: REEWA

- Euring code number: 12510

Alternate species names

- Catalan: boscarla de canyar

- Czech: rákosník obecný

- Danish: Rørsanger

- Dutch: Kleine Karekiet

- Estonian: tiigi-roolind

- Finnish: rytikerttunen

- French: Rousserolle effarvatte

- Gaelic: Ceileiriche-cuilc

- German: Teichrohrsänger

- Hungarian: cserrego nádiposzáta

- Icelandic: Sefsöngvari

- Irish: Ceolaire Giolcaí

- Italian: Cannaiola

- Latvian: ezeru kaukis

- Lithuanian: mažoji krakšle

- Norwegian: Rørsanger

- Polish: trzcinniczek (zwyczajny)

- Portuguese: rouxinol-dos-caniços

- Slovak: trsteniarik bahenný

- Slovenian: srpicna trstnica

- Spanish: Carricero común

- Swedish: rörsångare

- Welsh: Telor Cyrs

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

Breeding performance has increased, with some suggestion that this may be related to warming climate or improved habitat management, although the evidence for this is sparse.

Further information on causes of change

There is some evidence to suggest that this species may have benefited from warmer climates. Reed Warblers have shown a trend towards earlier laying (see above), which can be partly explained by recent climate change (Crick & Sparks 1999, Halupka et al. 2008). Halupka et al. (2008) analysed changes in breeding parameters of Polish Reed Warblers, studied during 12 breeding seasons between 1970 and 2006, and found that the onset of breeding advanced with warming temperatures, although the end of breeding did not change, thus resulting in an extension of the breeding season. The lengthening of the laying period by about three weeks meant that more birds were able to rear second broods. Furthermore, mean temperature during May-July correlated negatively with the proportion of nests that failed and there was some evidence of a positive relationship with the number of fledglings. Eglington et al. (2015) also suggest that the spread of Reed Warbler may be due to higher productivity stemming from increased temperatures. Experimental provision of supplementary food at two sites in South Wales led to advanced laying and increased productivity, indicating that food supply may be a limiting factor; hence suggesting a mechanism through which the trends may have occurred (Vafadis et al. 2016). Further research found that food-supplemented pairs spent more time incubating and showed a quicker response to the (simulated) presence of a predator (Vafadis et al. 2018).

The demographic data show a decrease in nest failures at the chick stage, although no trend was detected in the numbers of fledglings per breeding attempt, and a small improvement is apparent in CES productivity, although there is no available evidence to suggest that this is related to changing climate.

However, the suggestion that climate change has been a positive driver for this species is contradicted by modelling which concluded instead that the overall impact on the UK long-term trend for this species may have been negative, due to the negative effect of autumn temperatures in Spain (Pearce-Higgins & Crick 2019).

Both CBC/BBS and WBS/WBBS trends show progressive moderate increases perhaps linked to increasingly sensitive management of small and linear wetland sites. Thaxter et al. (2006) analysed data from two sites and found indirect evidence linking good habitat management to local abundance and survival.

As this species is a migrant it is possible that factors operating outside the breeding season may be responsible for changes in population in the UK. Thaxter et al. (2006) found that, unlike in the Sedge Warbler, rainfall in the Sahel region of West Africa did not account for variation in survival rates over time and did not correlate with variation in adult Reed Warbler abundance in the UK.

Julliard (2004) found that the French Reed Warbler population appears to be strongly regulated and that population growth rate was more influenced by survival rate than by recruitment.

Information about conservation actions

The population of this species increased between the 1970s and the early 2000s and has since been stable, hence it is not a species of concern and no conservation actions are currently required.

Continued improvements to wetland habitats and in particular the provision (and ongoing management) of Phragmites reedbeds are likely to continue to benefit this species which nests in very high concentrations within reedbeds. A study in the Netherlands found that Reed Warblers preferred uncut reeds to cut reeds when choosing nest territories and that the areas of uncut reed had higher nesting densities and lower predation rates (Graveland 1999).

The provision of supplementary food at breeding sites can help improve productivity (see Causes of Change section, above), although given the recent trends there is no evidence that food shortages are a significant problem currently for the UK population as a whole.

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).