Red Grouse

Introduction

Red Grouse inhabit heather moorland and are often flushed from cover before being seen; as they depart on whirring wings they may call 'go back go back'.

The Red Grouse was formely considered a subspecies of Willow Ptarmigan, but has recently been elevated to species status, making it the second species endemic to Britain and Ireland (Scottish Crossbill is endemic to Scotland). Individuals retain their reddish-brown plumage all year round and the males are territorial during winter, during which time they form pairs. Eggs are laid in a vegetation-lined scrape from April and the resulting chicks develop fast and are capable of flight at just two weeks of age.

Breeding Bird Survey data show the Red Grouse population to be cyclical, with numbers apparently influenced by parasite presence. Reliant on heather, Red Grouse habitat and associated fauna are intensively managed to maintain Red Grouse numbers for shooting from the "glorious" 12th August.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Grouse

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

The distinctive dark-winged race scotica is endemic to Britain and Ireland and the vast bulk of its population occurs within the UK, thus conferring global significance to the UK trend. Recent research has even suggested that Irish birds may be another separate race hibernicus (McMahon et al. 2012), although this remains unclear. The Red Grouse is economically significant to some rural communities as a game bird and has benefited from intensive management of moorland (particularly in the east of the country) designed specifically to increase the numbers of grouse available to be shot. BBS shows fluctuations but no overall trend since 1994. Shooting bags have revealed long-term declines which prompted the move of the species from the green to the amber list in 2002. Following the 2015 review (Eaton et al. 2015), Red Grouse remains on the amber list as the species (as a whole) is considered 'Vulnerable' in a European context. Montane Fennoscandian populations also declined during 2002-12 (Lehikoinen et al. 2014), however it is no longer listed for population decline in the UK.

Distribution

Red Grouse are characteristic of heather-dominated moorland in Britain and of raised and blanket bogs in Ireland. Being highly sedentary, the winter and breeding distribution maps are similar. Highest densities occur in the Pennines, North York Moors, Cheviot Hills, eastern Borders and the eastern Highlands of Scotland.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

There have been widespread range contractions, including apparent extinction of the southwest England population.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

Red Grouse are recorded throughout the year, especially in spring when they are very vocal and easily detected.

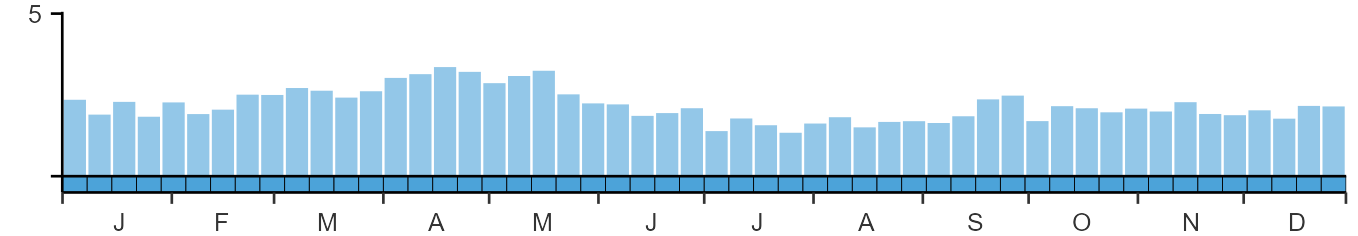

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

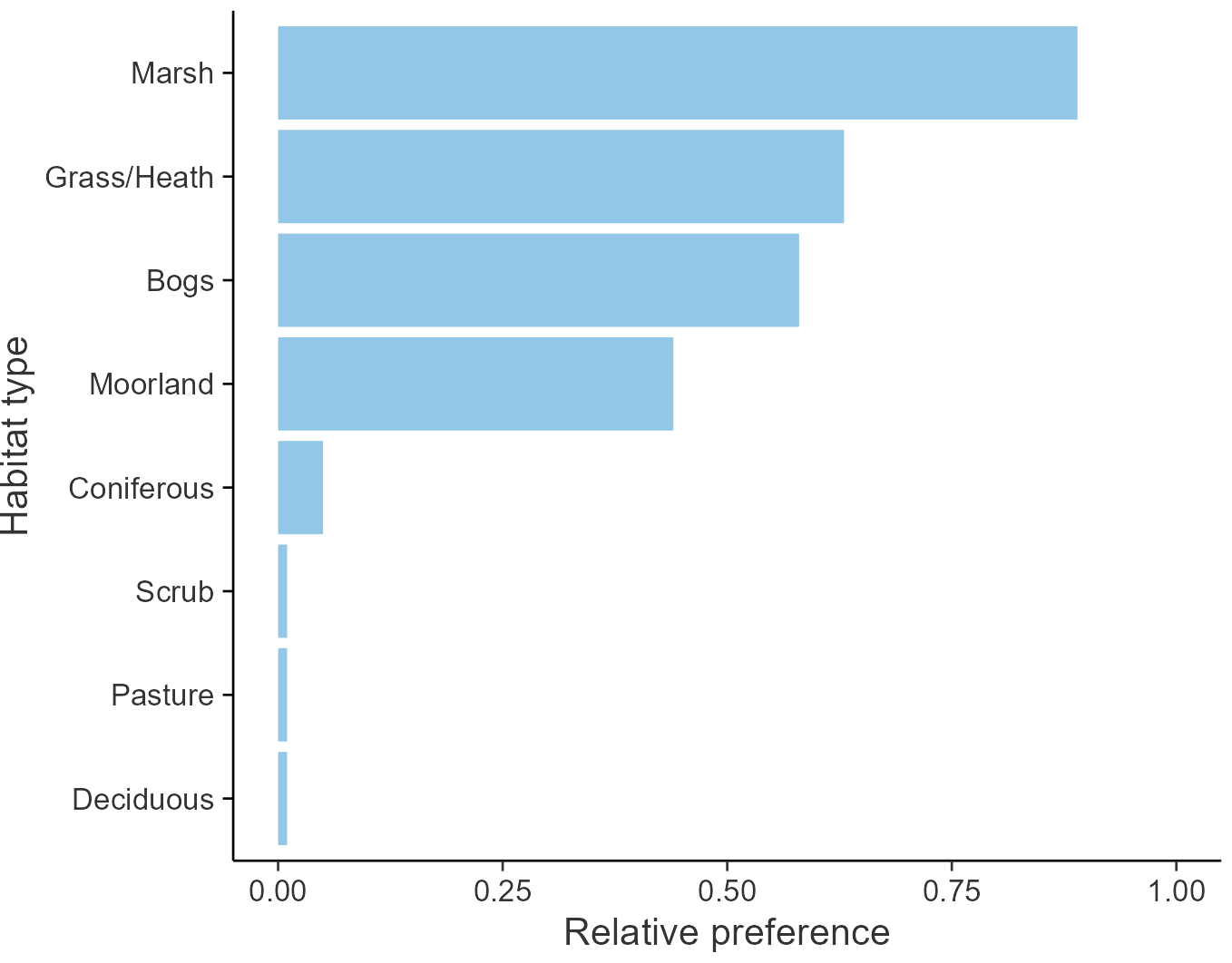

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Galliformes

- Family: Phasianidae

- Scientific name: Lagopus scotica

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: RG

- BTO 5-letter code: REDGR

- Euring code number: 3292

Alternate species names

- Catalan: perdiu boreal

- Czech: belokur rousný

- Danish: Dalrype

- Dutch: Moerassneeuwhoen

- Estonian: rabapüü

- Finnish: riekko

- French: Lagopède des saules

- Gaelic: Cearc-fhraoich

- German: Moorschneehuhn

- Hungarian: sarki hófajd

- Icelandic: Dalrjúpa

- Irish: Cearc Fhraoigh

- Italian: Pernice bianca nordica

- Latvian: (baltirbe), teteris

- Lithuanian: paprastoji žvyre

- Norwegian: Lirype

- Polish: pardwa mszarna

- Portuguese: lagopo-ruivo

- Slovak: snehula kapcavá

- Slovenian: barjanski jereb

- Spanish: Lagópodo común

- Swedish: dalripa

- Welsh: Grugiar Goch

- English folkname(s): Grouse, Heather Cock

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

Longer-term trends in Red Grouse abundance are overlain by cycles, with periods that vary regionally, linked to the dynamics of infection by a nematode parasite and to interrelated variations in the aggressiveness of males in autumn.

Further information on causes of change

Given its economic significance, long-term population trends of Red Grouse are likely to be closely associated with changes in management practices (see below). Shooting bags have revealed long-term declines, apparently driven by a combination of a loss of heather moorland, increased predation from corvids and foxes, and an increasing incidence of viral disease (Hudson 1992, Newton 2004). However, these trends appear to be overlain by cycles, with periods that vary regionally, linked to the dynamics of infection by a nematode parasite Trichostrongylus tenuis (Dobson & Hudson 1992, Gibbons et al. 1993) and to interrelated variations in the aggressiveness of males in autumn (Martinez-Padilla et al. 2014). Recent increases in the Red Grouse population have been attributed to the use of higher strengths of medicated grit (Thompson et al. 2016).

Strip burning of heather is undertaken to increase suitable habitat for Red Grouse. Although the short-term effect is to reduce the abundance of birds using the recently burnt areas (Douglas et al. 2017), densities subsequently increase most in areas where heather recovery is greatest (Ludwig et al. 2018c). Analysis of game bag data since 1890 linked population changes to changes in keeper density and afforestation (Robertson et al. 2017). However the wider environmental impacts of moorland management for grouse are contested (Thompson et al. 2016, Sotherton et al. 2017). Whilst long-term declines are most likely linked to habitat changes (Thirgood et al. 2000), raptor predation may subsequently have limited population growth at some sites (Thirgood et al. 2000, Roos et al. 2018). In a study looking at four upland areas in the UK, higher Red Grouse abundance was correlated positively with higher predator control (Buchanan et al. 2017), and abundance and breeding success was higher at a Scottish site in years when predators were controlled (Ludwig et al. 2017). Other studies have concluded that mortality associated with raptors are important factors in survival but could not exclude scavenging so may have over-estimated true predation (Ludwig et al. 2018b, Francksen et al. 2019).

Hen Harriers in particular can reduce grouse shooting bags, limit grouse populations and cause economic losses to moor owners, which has led to instances of illegal persecution (Thompson et al. 2009, 2016, Murgatroyd et al. 2019; see also Conservation Actions section, below).

Laying dates in the Scottish Highlands advanced by about ten days between 1992 and 2011, and were inversely correlated with pre-laying temperatures, but no overall effect of climate change on chick survival could be identified (Fletcher et al. 2013).

At Langholm Moor, Red Grouse productivity was lower, suggesting higher chick predation, in years with high vole abundance; the reasons for this were unclear but were believed to be more consistent with the hypothesis that 'apparent competition' was occurring between voles and grouse, rather than the 'alternative prey' hypothesis, i.e. that incidental grouse chick predation is higher when increased vole numbers attract more predators (Ludwig et al. 2020b).

Information about conservation actions

This species is Amber-listed in the UK due to its European status; however, the fluctuating BBS trend does not raise any alerts and so does not give cause for concern. The species benefits from intensive management of moorland, to increase numbers available to be shot, and therefore no specific additional conservation actions are currently required.

Some observers have questioned the legitimacy of grouse shooting if it is only viable when birds of prey are routinely killed (Thompson et al. 2009), whilst others contend that grouse shooting protects the conservation of heather moorland and hence populations of some declining birds such as waders that depend upon it (Sotherton et al. 2009). The relative importance of predation and habitat management on numbers of Red Grouse, and on the wider environment including other moorland birds, in particular Hen Harrier, is the source of much debate with strongly opposing views (Redpath & Thirgood 2008, Thompson et al. 2016, Sotherton et al. 2017, Hodgson et al. 2018, 2019, St John et al. 2018). This has consequences for wider moorland management and the bird populations that live there (Redpath & Thirgood 2009, Thompson et al. 2016). The final report of the Langholm Moor Demonstration project concluded that whilst some targets had been met, the project was unable to achieve compatibility for management between raptor and Red Grouse interests and grouse numbers remained insufficient to make driven shooting viable (LMDP Partners 2019).

Publications (1)

Nesting dates of Moorland Birds in the English, Welsh and Scottish Uplands

Author:

Published: 2022

Rotational burning of vegetation is a common form of land management in UK upland habitats, and is restricted to the colder half of the year, with the time period during which burning may be carried out in upland areas varying between countries. In England and Scotland, this period runs from the 1st October to 15th April, but in the latter jurisdiction, permission can be granted to extend the burning season to 30th April. In Wales, this period runs from 1st October to 31st March. This report sets out timing of breeding information for upland birds in England, Scotland and Wales, to assess whether rotational burning poses a threat to populations of these species, and the extent to which any such threat varies in space and time.

17.02.22

BTO Research Reports

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).