Linnet

Introduction

Widely distributed across Britain & Ireland all year round, this small finch is a species of open country and farmland.

UK Linnet numbers fell sharply between the late-1960s and the late-1980s. Since then, the decline has slowed, but the overall population trend is still on a downward trajectory. This negative trend is thought to be linked to increased nest failure associated with agricultural intensification. The Linnet has been on the UK Red List since 1996.

Linnets have an overall streaky brown appearance. Males have more distinctive plumage than females, with a grey head and pink patches on the forehead and chest. They also have a very melodious song. Linnets form big flocks during the winter months, sometimes mixing with other finches, combing the countryside in search of seeds to eat.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Linnet & Twite

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Linnet abundance fell rapidly in the UK in the late 1960s, and again between the mid 1970s and mid 1980s, but decrease has been followed by a long period of relative stability. Numbers have fallen further since the start of BBS in 1994. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that, in both Britain and Northern Ireland, there was decrease over that period in eastern regions and increase in the west. There has been a decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

Linnets require scattered bushes or scrub for nesting and seeds in the surrounding landscape for food. They are widely distributed through the breeding season, being found in virtually every 10-km square in England, Wales and Ireland. In Scotland, however, they are restricted to lower ground. During winter Linnets withdraw from upland areas and therefore have a slightly more restricted distribution than in the breeding season.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Breeding range extent has changed little, but abundance changes differ by region, with large increases in Ireland and in parts of northern and western Scotland, but declines on lower ground elsewhere in Britain.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

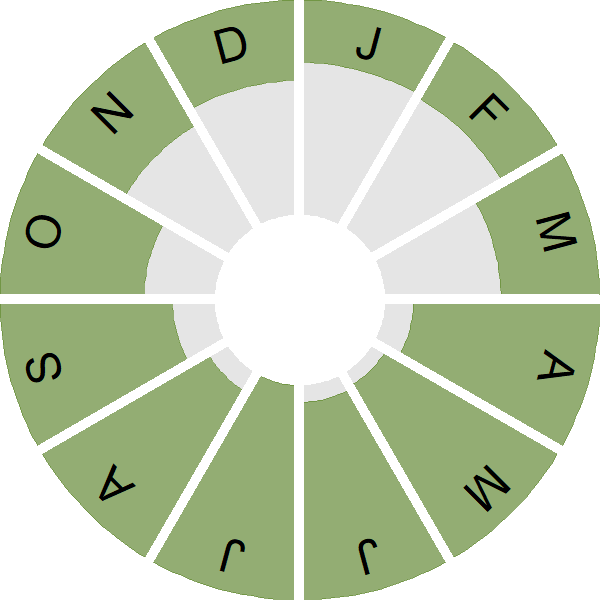

Seasonality

Linnet is recorded throughout the year, in flocks in winter and more dispersed and widely detected in the breeding season.

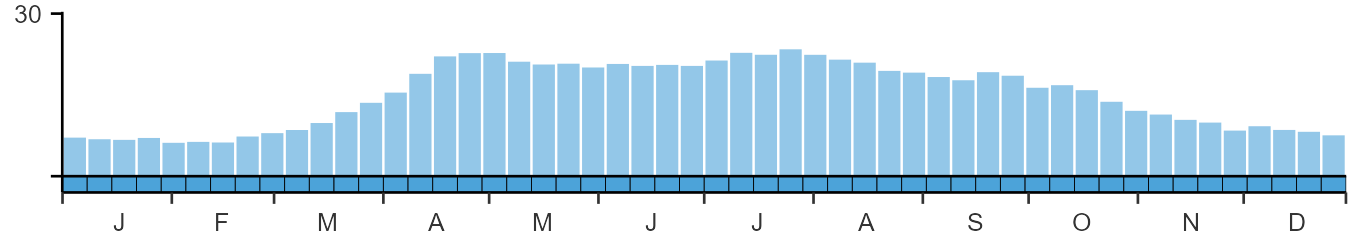

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

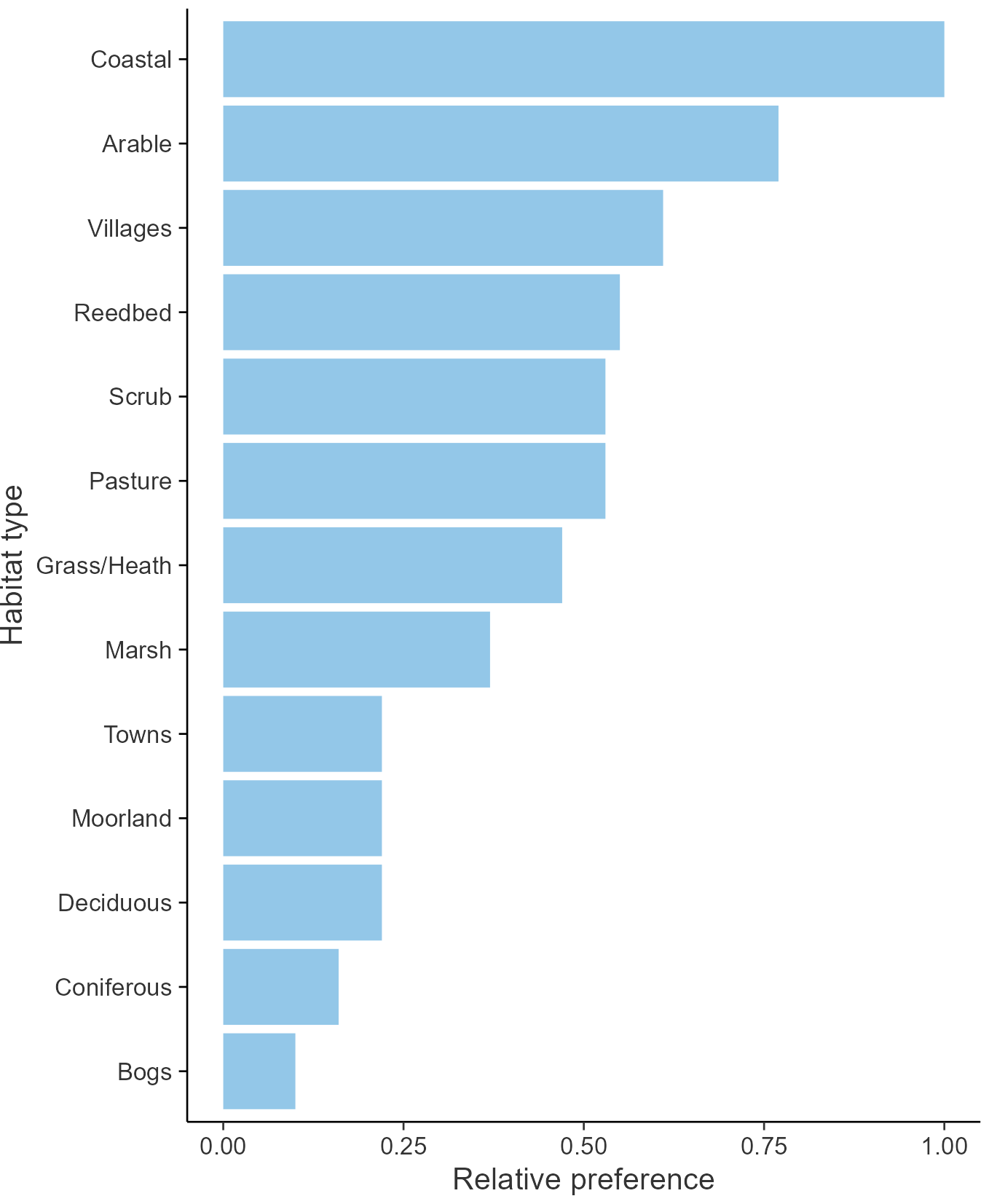

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Fringillidae

- Scientific name: Linaria cannabina

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: LI

- BTO 5-letter code: LINNE

- Euring code number: 16600

Alternate species names

- Catalan: passerell comú

- Czech: konopka obecná

- Danish: Tornirisk

- Dutch: Kneu

- Estonian: kanepilind

- Finnish: hemppo

- French: Linotte mélodieuse

- Gaelic: Gealan-lìn

- German: Bluthänfling

- Hungarian: kenderike

- Icelandic: Hörfinka

- Irish: Gleoiseach

- Italian: Fanello

- Latvian: kanepitis

- Lithuanian: eurazinis civylis

- Norwegian: Tornirisk

- Polish: makolagwa (zwyczajna)

- Portuguese: pintarroxo

- Slovak: stehlík konôpka

- Slovenian: repnik

- Spanish: Pardillo común

- Swedish: hämpling

- Welsh: Llinos

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There is convincing evidence that nest failure rates rose during the principal period of population decline and this represents the most likely demographic mechanism driving the observed decreases in abundance. The most likely ecological driver of this pattern is habitat impoverishment due to agricultural intensification.

Further information on causes of change

Siriwardena et al. (1999, 2000b) provide convincing evidence that nest failure rates at the egg stage rose during the principal period of population decline and this represents the most likely demographic mechanism driving the observed decrease in abundance. They found an obvious change in the egg-stage failure rate of Linnet nests after 1975 and this was detectable in the total fledglings produced, suggesting that the deterioration in breeding performance had an important role in driving the species' concurrent decline in abundance (Siriwardena et al. 2000b). Moorcroft & Wilson (2000) concur that the severe decline during the 1970s and 1980s occurred via a reduction in breeding success, attributing this to a reduction in the availability of breeding-season food supplies on arable farmland caused by agricultural intensification. However, they state that the precise demographic mechanism involved is unclear: instead of breeding performance per attempt, they suggest reductions in the number of nesting attempts being made by individual females or a reduction in immediate post-fledging survival due to resource limitations as more likely, although these hypotheses were not tested. BTO monitoring data do not permit analysis of these parameters but it is plausible that such effects occurred in parallel with the breeding success effects indicated by NRS results. Nevertheless, all these patterns are consistent with the results of Siriwardena et al. (1999), who reported that index change was not significantly correlated with adult and first-year survival. They found no significant trend-specific difference in survival, and survival rates in periods of decline were higher than those in periods of increase.

After 1986, egg-stage nest survival increased and this led to a slight increase in breeding performance, although, as with the earlier decline, greater numbers of breeding attempts or increased post-fledging survival may also have contributed to the ending of population decline (Siriwardena et al. 2000b, Wilson et al. 1996, Moorcroft et al. 1997). Increases in the crop area of oilseed rape are thought to have improved Linnet breeding success by compensating for the herbicide-mediated decline in many farmland weeds that were traditionally important in this species' summer diet (Moorcroft et al. 1997). Both the number of breeding attempts possible in a season and post-fledging survival could have increased in response to this improvement in food supplies, as could chick survival. Oddly, Siriwardena et al. (2001b) identified a significant negative effect of rape on breeding performance through the egg-stage daily nest failure rate and no positive effect on success through the nestling stage in a further analysis of nest record data. This is clearly inconsistent with the results of intensive work on Linnets (Wilson et al. 1996, Moorcroft et al. 1997), perhaps reflecting the different geographical biases affecting nest records and this particular intensive study. Nevertheless, it suggests that environmental effects on Linnet breeding success show complex spatial variation and that the knock-on effects on trends in abundance could also be difficult to characterise. Modelling suggests that climate change may have had a positive impact on the long-term trend for this species, resulting in less negative trends than would have occurred in the absence of climate change (Pearce-Higgins & Crick 2019).

The current long-term pattern, spanning the Linnet's periods of decrease and relative stability, is of linear increase in nest failure rates and linear decline in the number of fledglings per breeding attempt.

Information about conservation actions

The decline of this species has been linked to decreased breeding success as a result of agricultural intensification. However, the exact mechanism behind the decline remains unclear and hence no specific conservation actions have been recommended relating to this species.

However, actions and policies aimed at helping other farmland species are also likely to benefit Linnets, in particular those aimed at improving breeding habitat and food availability during the breeding season (e.g. management of hedgerows, reducing pesticide and herbicide use and set-aside). One study suggested that increases in the crop area of oilseed rape may have improved Linnet breeding success (Moorcroft et al. 1997) but this was not supported by another study (Siriwrdena et al. 2001b, see Causes of Change section).

Although the decline in the 1970s and 1980s is believed to have been caused by problems during the breeding season, actions aimed at increasing food availability over winter could also benefit Linnet if they increase overwinter survival (e.g. overwinter stubbles, wild bird seed or cover mixtures, set-aside, buffer strips or uncultivated margins). One study in central England found that Linnets were found more frequently on barley stubbles than on wheat stubbles (Moorcroft et al. 2002), which is likely to be due to greater spillage losses of grain during harvesting of barley crops (e.g. Stacey et al. 2006).

Publications (2)

The benefits of protected areas for bird population trends may depend on their condition

Author:

Published: 2024

BTO-led research highlights the importance of the quality of protected areas in their effectiveness.

28.03.24

Papers

Breeding periods of hedgerow-nesting birds in England

Author:

Published: Spring 2024

Hedgerows form an important semi-natural habitat for birds and other wildlife in English farmland landscapes, in addition to providing other benefits to farming. Hedgerows are currently maintained through annual or multi-annual cutting cycles, the timing of which could have consequences for hedgerow-breeding birds. The aim of this report is to assess the impacts on nesting birds should the duration of the management period be changed, by quantifying the length of the current breeding season for 15 species of songbird likely to nest in farmland hedges. These species are Blackbird, Blackcap, Bullfinch, Chaffinch, Dunnock, Garden Warbler, Goldfinch, Greenfinch, Linnet, Long-tailed Tit, Robin, Song Thrush, Whitethroat, Wren and Yellowhammer.

05.03.24

BTO Research Reports

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).