Kingfisher

Introduction

Despite its brightly-coloured plumage, the Kingfisher can be a challenging bird to spot when perched on a waterside branch. More often than not you will be first alerted to its presence by its piping call.

Widely distributed on lowland rivers and still-waters, the Kingfisher is a species whose fortunes have waxed and waned. Numbers are impacted by severe winter weather, and this may be the main driver of change, but changing water quality and availability of favoured prey may also play a role.

Kingfishers may move away from their breeding territories during the winter months, including to more coastal sites, in order to reduce the impacts of poor winter weather on fishing opportunities.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Flight call:

Begging call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

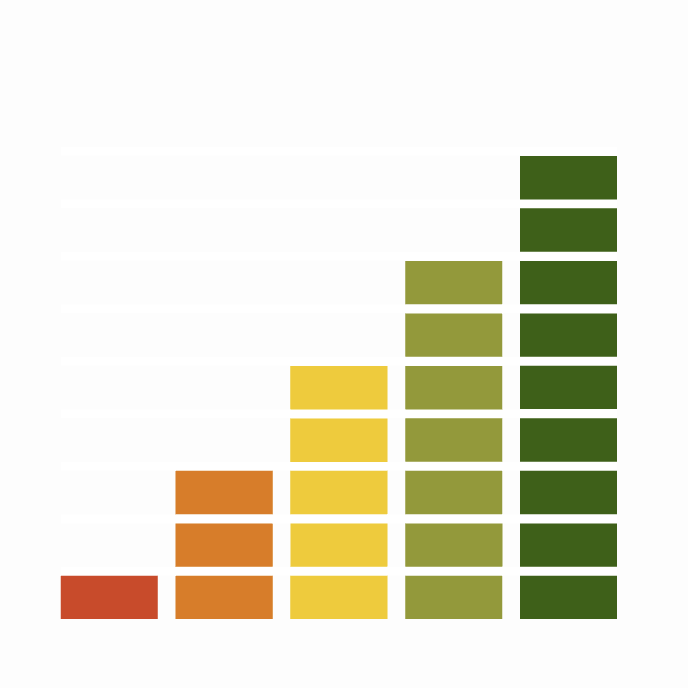

Population Change

The Kingfisher declined along linear waterways (its principal habitat) until the mid 1980s, since when it seems to have made a complete recovery, only to enter another decline, though numbers are still much higher now than in the mid 1980s. The initial decline was associated with a contraction of range in England (Gibbons et al. 1993). Though the amber listing of this species in the UK results from its 'depleted' status in Europe as a whole, numbers across Europe have fluctuated but have been broadly stable since 1991 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

Kingfishers are widely distributed on the lowland rivers of Britain & Ireland. They are resident, with some dispersal away from breeding territories outside the breeding period, especially by juvenile birds. In Britain this may explain the greater number of 10-km squares occupied in winter than in the breeding season.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Patterns of distribution change indicate large gains in winter range in both Britain and Ireland since the 1981–84 Winter Atlas, when numbers were at a low point following several cold winters.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

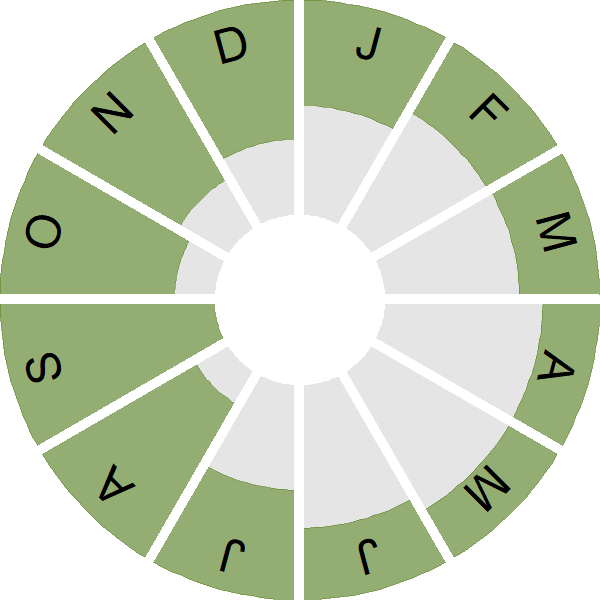

Seasonality

Kingfishers are present throughout the year, though more likely to be recorded post-breeding in autumn.

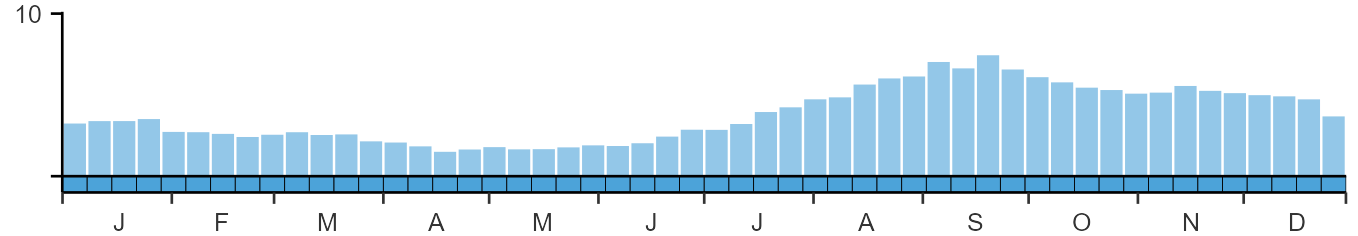

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

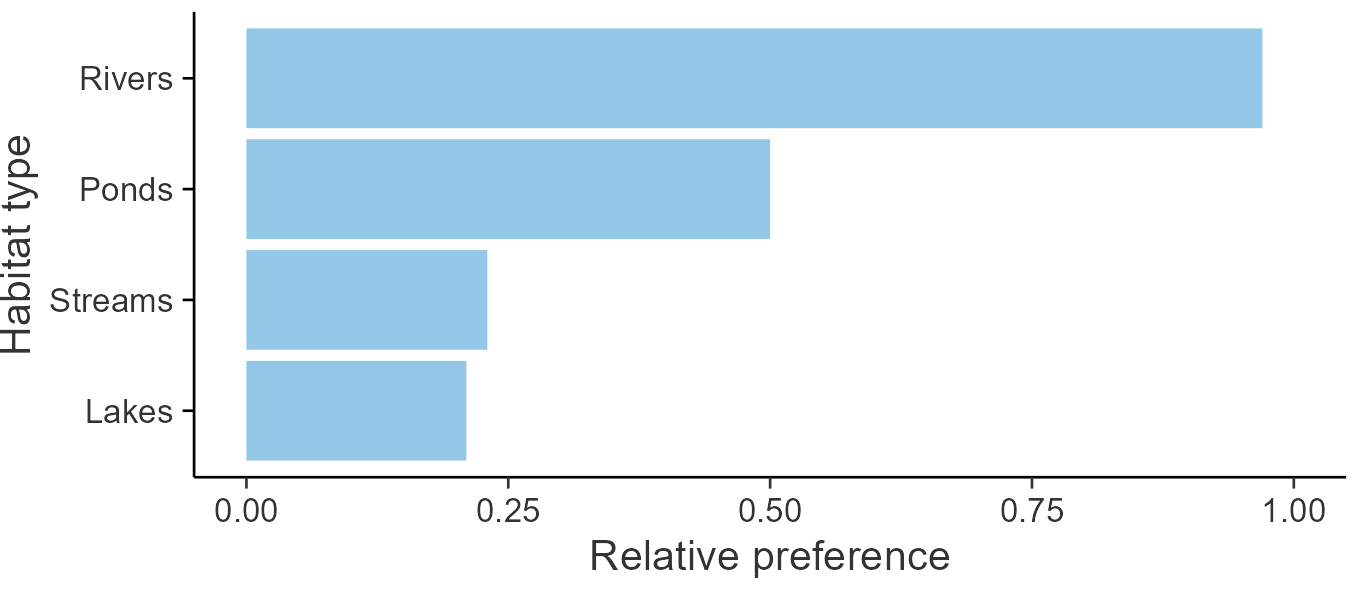

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Coraciiformes

- Family: Alcedinidae

- Scientific name: Alcedo atthis

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: KF

- BTO 5-letter code: KINGF

- Euring code number: 8310

Alternate species names

- Catalan: blauet comú

- Czech: lednácek rícní

- Danish: Isfugl

- Dutch: IJsvogel

- Estonian: jäälind

- Finnish: kuningaskalastaja

- French: Martin-pêcheur d’Europe

- Gaelic: Biorra-crùidein

- German: Eisvogel

- Hungarian: jégmadár

- Icelandic: Bláþyrill

- Irish: Cruidín

- Italian: Martin pescatore

- Latvian: zivju dzenitis

- Lithuanian: paprastasis tulžys

- Norwegian: Isfugl

- Polish: zimorodek (zwyczajny)

- Portuguese: guarda-rios

- Slovak: rybárik riecny

- Slovenian: vodomec

- Spanish: Martín pescador común

- Swedish: kungsfiskare

- Welsh: Glas y Dorlan

- English folkname(s): Halcyon

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

It is likely that winter weather is the main cause of population change for Kingfisher, although the possible effects of other potential longer term drivers of change (e.g. changes to water quality) have not been investigated.

Further information on causes of change

Kingfishers suffer severe mortality during harsh winters (for instance in the 1981/82 winter) but, with up to three broods in a season, and up to six chicks in a brood, their potential for rapid population growth is high. It is likely, therefore, that winter weather is the main driver of population change.

Information about conservation actions

Whilst severe weather is believed to be the main driver of annual population changes for this species, continued improvements to water quality and the provision of new wetland habitats are likely to have benefitted this species.

The provision of artificial nesting sites may enable this species to breed at sites where good quality natural nesting sites are limited or absent. This may include artificial sand or earth banks (Hopkins 2001) or alternative options such as artificial burrows drilled into a limestone cliff which were used by both Sand Martins and Kingfisher (Gulickx et al. 2007).

Publications (1)

Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4: the population status of birds in Wales

Author:

Published: 2022

The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List, with 91 on the Amber List and just 69 - less than a third of the total number of species - on the Green List. The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales comes 20 years after the first, when the Red List was less than half the length it is today. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List in Wales, with 91 on the Amber List and 69 on the Green List. The Birds of Conservation Concern in Wales report assesses the status of each species against a set of objective criteria. Data sources include the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey and the BTO/RSPB/JNCC Wetland Bird Survey, as well as Bird Atlases and other BTO-led monitoring schemes and citizen science initiatives. These are used to quantify the changing status of the species’ Welsh population. The UK, European and global conservation status of the species is also considered, placing the Welsh population into a wider context. The Red ListSwift, Greenfinch and Rook – familiar breeding species in steep decline across the UK – are among the new additions to the Welsh Red List, which now also includes Purple Sandpiper, on account of a rapidly shrinking Welsh wintering population, and Leach’s Petrel, an enigmatic seabird in decline across its global range. These species now sit alongside well-known conservation priorities, such as Curlew, Hen Harrier and Turtle Dove as birds at risk of being lost from Wales for good. Uplands and woodlands Many of the species on the Red List are found in upland and farmland habitats. Starling, Tree Sparrow, Yellow Wagtail and Yellowhammer can no longer be found in much of Wales, while iconic species of mountain and moorland, such as Ring Ouzel, Merlin and Black Grouse, remain in serious trouble. Wales is well known for its populations of woodland birds; however, many of these – including Lesser Spotted Woodpecker, Willow Warbler and Spotted Flycatcher – also feature on the Red List. Goldcrest, which has seen its Welsh population shrink alarmingly in recent decades, is another new addition. On the coast The assessment for Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4 took place before the impacts of avian influenza could be taken into account. Breeding seabird species have been struggling in Wales for many years, however, and most were already of conservation concern before the outbreak of this disease. Kittiwake, Puffin, Black-headed Gull, and Common, Arctic and Sandwich Tern remain on the Red List. Wales holds internationally significant numbers of breeding seabirds, making the decline of these colonies a global concern. The Amber ListDeclines in Wheatear, Garden Warbler and House Martin - all migrants which breed in Europe and winter in sub-Saharan Africa - mean these species have moved from the Green List to the Amber List. Many other ‘Afro-Palearctic' migrant species are also in decline, but the potential reasons for this, such as habitat loss and reduced availability of invertebrate prey, are not well understood. Closer to home, the declines in the Welsh Chaffinch population, linked to the disease trichomonosis, have seen the species Amber-listed. A number of other species have been placed on the Amber List because of the wider importance of their Welsh populations, which in each case make up more than half the UK total. Wales is home to more than three-quarters of the UK’s Choughs, for example, so recent declines are cause for concern. The nation’s breeding populations of Manx Shearwater, Pied Flycatcher, Goshawk and Hawfinch also account for more than half the UK total, as does its wintering population of Spotted Redshank. It’s not all bad news, though: some species now on the Amber List have moved up from the Red List, indicating some positive change in their population trends. These include Common Sandpiper, Great Black-backed Gull, Bullfinch, Goldcrest and Pied Flycatcher. The Green ListWhile the report contains much cause for alarm, several conservation success stories shine through. Red Kite was almost lost as a British bird during the first half of the 20th century, when only a handful of pairs remained in remote Welsh valleys. Since then, a sustained conservation effort has brought the species back from the brink. Wales is now home to more than 2,500 pairs of Red Kite and the species has now been moved to the Green List, reflecting this incredible change in fortunes. Song Thrush, Reed Bunting, Long-tailed Tit, Redwing and Kingfisher are among the other species to have gone Green, providing much-needed hope that things can go up as well as down.

06.12.22

Reports Birds of Conservation Concern

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).