House Sparrow

Introduction

Cheeping flocks of House Sparrow once tumbled from untidy nests and wallowed in urban dust baths. Now the species is in decline and has been on the UK Red List since 2002.

Colonial nesters, the male House Sparrow is resplendent with grey head and black bib, while the female and young are more uniformly brown. Very much associated with the dwellings of man whether urban or rural, House Sparrows enjoy a mixed diet, and in the summer will readily forage for insects in hedgerows and meadows providing they do not have to fly too far from their nests.

House Sparrows are found year round throughout Britain & Ireland, except for on the highest peaks. The species has declined in the UK since the mid-1970s, with losses most notable in the south and east.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Sparrows

#BirdSongBasics: House Sparrow and Dunnock

GBW: House Sparrow and Dunnock

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Begging call:

Other:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

CBC sample sizes did not allow monitoring of House Sparrows until 1976; previously, there had been many farmland plots with high populations that CBC volunteers could not properly quantify without better access to farm buildings and housing. CBC/BBS data indicate a rapid decline in abundance over the last 25 years, as does the BTO's Garden Bird Feeding Survey (Siriwardena et al. 2002, Robinson et al. 2005b). These results are supported by many other studies and anecdotal reports, and have generated considerable conservation concern (see Summers-Smith 2003). The overall national decline since the 1970s masks much heterogeneity by region and habitat, and population processes may be relatively fine-grained: overall, populations in rural areas had declined by 47% by 2000, and those in urban and suburban areas by about 60% (CBC and GBFS data: Robinson et al. 2005b). The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that the decline was strongest over that period in the London area and eastern Britain generally, while increases occurred in parts of western Britain. The current BBS data show significant increases in Scotland and Wales since 1995, although these are dwarfed by the earlier UK decline. A change in the listing criteria resulted in the admission of the species, green-listed until 2002, directly to the red list. There has been a decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>). The European status of this species is no longer considered 'secure' (BirdLife International 2004).

Distribution

The House Sparrow is among the most widespread species in Britain & Ireland, being found in c.90% of 10-km squares; it is absent only from exposed upland areas of northern Scotland. Abundance is generally higher in lowland areas, although densities are low in southeast England and East Anglia.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Both winter and breeding range have remained largely stable despite an extensive population decline since the 1970s.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

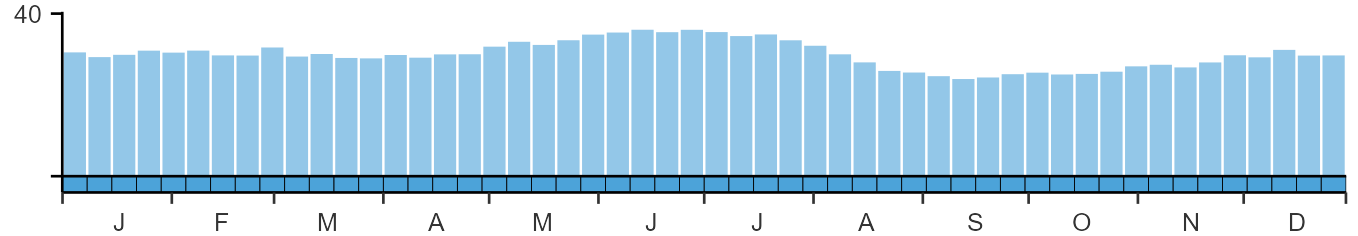

House Sparrow is recorded throughout the year on up to 40% of complete lists.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

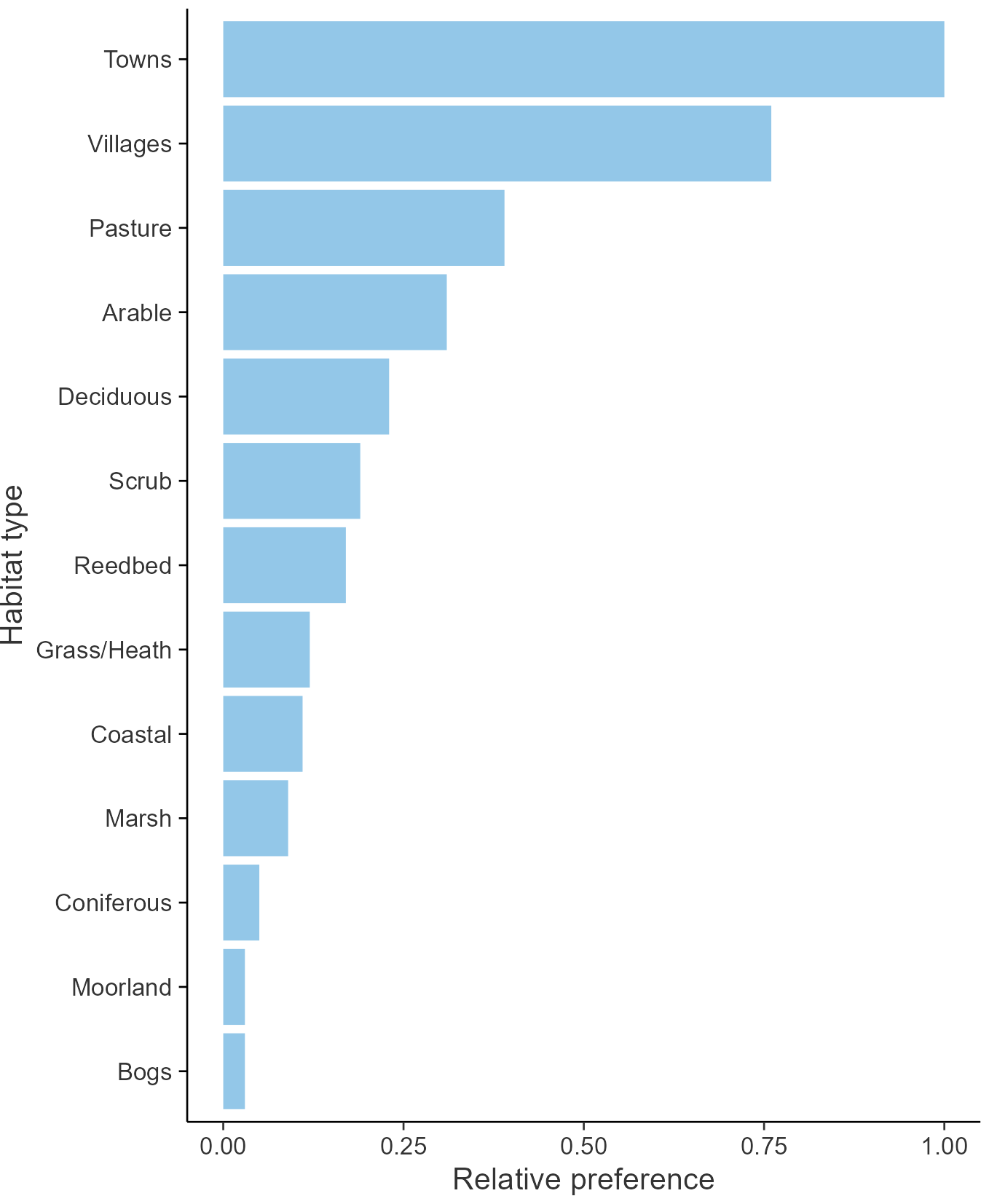

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Passeridae

- Scientific name: Passer domesticus

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: HS

- BTO 5-letter code: HOUSP

- Euring code number: 15910

Alternate species names

- Catalan: pardal comú

- Czech: vrabec domácí

- Danish: Gråspurv

- Dutch: Huismus

- Estonian: koduvarblane

- Finnish: varpunen

- French: Moineau domestique

- Gaelic: Gealbhonn

- German: Haussperling

- Hungarian: házi veréb

- Icelandic: Gráspör

- Irish: Gealbhan Binne

- Italian: Passera Europea

- Latvian: majas zvirbulis

- Lithuanian: naminis žvirblis

- Norwegian: Gråspurv

- Polish: wróbel (zwyczajny)

- Portuguese: pardal

- Slovak: vrabec domový

- Slovenian: domaci vrabec

- Spanish: Gorrión común

- Swedish: gråsparv

- Welsh: Aderyn y Tô

- English folkname(s): Speug, Spadger

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There is evidence that changes in survival rates due to lack of food resources, because of agricultural intensification, are the main driver of House Sparrow declines in farmland, although changes in breeding performance may also have played a role. Different processes have affected House Sparrows in towns, where breeding performance could be the most important driver of declines, although the evidence for the ecological causes is less clear.

Further information on causes of change

A temporary drop in first-year survival coincided with the period of steepest decline, but changes in breeding performance, especially reduced nest failure rates at the chick stage, appear to have driven a levelling-off in the long-term population trend (Freeman & Crick 2002). Over the period since 1968, brood size has decreased (see above) but there has also been a major decrease in nest failure rates at the egg and chick stages, so the number of fledglings per breeding attempt has shown a net increase. Further evidence for the role of changing survival in House Sparrow declines has been provided by Hole et al. (2002), who found no evidence of significant differences in most breeding-ecology parameters in declining and stable populations in a farm-scale comparison, while Siriwardena et al. (1999) found that national survival rates were lower during the period of decline in the CBC index. That survival, especially of adult birds, appeared to make the largest contribution to annual population change was also found by Robinson et al. (2014). Crick & Siriwardena (2002), using NRS data, showed that breeding performance per nesting attempt had increased and was positively correlated with population growth rate in the wider countryside (although there was no such correlation in gardens). Analysis of Garden BirdWatch data found higher seasonal peak counts, however, relative to pre-breeding numbers, in the north and west of Britain than in the east and south where population decline is strongest, thus indicating that breeding productivity is influencing population trends (Morrison et al. 2014).

There appear to be different processes affecting urban and agricultural populations. On farmland, changes in farming practices due to intensification of agriculture and the tidying of farmyards have reduced the seed available to farmland populations of House Sparrows during winter, which has resulted in a reduction in survival rates (Siriwardena et al. 1999, Chamberlain et al. 2007, Hole 2001), specifically of first-year birds (Crick et al. 2002). This is supported by a positive effect of supplementary seed in winter on farmland House Sparrow population trends in a landscape-scale experiment in East Anglia (Siriwardena et al. 2007), and a similar positive effect from the provision of areas of seed rich habitat on farms under agri-environment schemes in Northern Ireland (Coulhoun et al. 2017). House Sparrows have probably been deleteriously affected by the decrease in the amount of grain spilt around farm buildings and during the process of harvesting since the 1970s (O'Connor & Shrubb 1986). The move towards autumn-sowing of cereals has meant that cereal stubble has become much rarer, reducing food resources over winter, although Robinson et al. (2001) found no influence of spring-sown cereal on House Sparrow abundance in predominantly pastoral farmland. Conversely, breeding performance is worse where there is more spring cereal (Crick & Siriwardena 2002), although this may reflect geographical associations with areas where spring sowing remains widespread in the UK (the west and north) rather than direct effects of cropping.

Recent declines have been particularly severe in urban areas (Robinson et al. 2005b, Chamberlain et al. 2007). Increased predation by cats and Sparrowhawks, lack of nest sites, loss of food supplies, pollution and disease have all been cited as factors possibly depressing populations in towns (Crick et al. 2002), but supporting evidence for these is mixed. Within urban areas, Shaw et al. (2008) reviewed available evidence and hypothesised that House Sparrows have disappeared from more affluent areas, where changes to habitat structure such as planting of ornamental shrubs and increased demand for off-street parking is likely to reduce the amount of habitat available to House Sparrows and influenced foraging and predation risk. The conversion of private gardens to continuous housing has also had a negative effect on House Sparrow abundan

Vincent (2005) found that annual productivity among suburban and rural human habitation in Leicestershire was lower than that measured on farmland House Sparrows in Oxfordshire, the main cause of the difference being starvation of chicks. Low body masses at fledging, and consequently low post-fledging survival, were also recorded in Leicestershire. Although only a two-year study, Peach et al. (2008) measured reproductive success in a declining House Sparrow population along an urbanisation gradient in Leicester and also found that a year in which reproductive success was too low to sustain the population was characterised by lower chick survival and body mass at fledging (a predictor of post-fledging survival). However, there is no direct evidence that invertebrate food supplies have declined in these areas and variation in survival has not been investigated. Supplying mealworms for garden-nesting House Sparrows in Greater London substantially improved breeding success but did not increase nesting density (Peach et al. 2014, 2015). Supplying unlimited high energy seed throughout the year did not affect overwinter or survival or population size, suggesting that food availability was not currently a limiting factor for suburban sparrows (Peach et al. 2018).

Analysis of cross-colony abundance in Greater London found that numbers were higher in areas with more seed rich habitat and low levels of nitrogen dioxide air pollution, although further evidence about the effects of air pollution are needed to confirm whether it may have contributed to the decline (Peach et al. 2018). There is evidence, however, that avian malaria may have contributed to the decline in London, where infection was found at very high prevalence and survival rates were negatively correlated with infection rates (Dadam et al. 2019).

Negative correlations between indices of Sparrowhawk presence during its post-organochlorine increase and House Sparrow abundance from the Garden Bird Feeding Survey have been interpreted as evidence that increasing predation rates are depressing House Sparrow populations (Bell et al. 2010). However, more sophisticated analyses of large-scale and extensive national monitoring data provide no evidence that House Sparrow population declines were linked to increases in Sparrowhawks (Newson et al. 2010b).

Information about conservation actions

The main driver of the decline in farmland is believed to be a reduction of food resources on farms and in farmyards as a result of agricultural intensification, and therefore conservation actions and agri-environment policies which increase food availability are likely to benefit House Sparrows in rural areas. Research has confirmed positive effects from the provision of supplementary seed in winter (Siriwardena et al. 2007) and from the provision of areas of seed-rich habitat on farms (Colhoun et al. 2017).

The evidence relating to the declines in urban areas is less clear and further research is still needed. It may be that a number of different causes are affecting populations (see Causes of Change section, above). Therefore, a variety of different actions could be needed to reverse the declines, and actions that have increased numbers at some colonies will not necessarily be successful elsewhere. Providing supplementary food during winter may help declining populations (Hole et al. 2002) and actions to increase densities of invertebrates away from major roads may help improve breeding productivity (Peach et al. 2008). Actions to maintain and improve habitat in urban areas could also help, including the planting of native shrubs in gardens (Wilkinson 2010), retaining natural gardens and green spaces rather than paving, and ensuring suitable nesting locations are available (e.g. by providing nest boxes). Other possible causes which could have contributed to the decline include avian malaria (Dadam et al. 2009), for which encouraging improved garden feeder hygiene is important; and air pollution, which may be more difficult to resolve without wider scale policies.

Publications (5)

Drivers of the changing abundance of European birds at two spatial scales

Author:

Published: 2023

Understanding how human activities drive biodiversity change at different spatial scales is a key question for conservation practitioners and decision-makers. While we have a good understanding of the primary causes of observed biodiversity declines – which include land-use change, climate change, pollution, and the over-exploitation of species – we still struggle to measure and detect biodiversity change in robust and meaningful ways.

29.05.23

Papers

The State of the UK's Birds 2020

Author:

Published: 2020

The State of UK’s Birds reports have provided an periodic overview of the status of the UK’s breeding and non-breeding bird species in the UK and its Overseas Territories since 1999. This year’s report highlights the continuing poor fortunes of the UK’s woodland birds, and the huge efforts of BTO volunteers who collect data.

17.12.20

Reports State of the UK's Birds

Avian malaria-mediated population decline of a widespread iconic bird species

Author:

Published: 2019

England’s House Sparrow population fell by 70% between 1977 and 2016, and this once ubiquitous species is now absent from many urban areas. New research involving the BTO has found evidence that malarial parasites may be linked to this species’ decline. During a three-year study led by the ZSL Institute of Zoology, in collaboration with the RSPB and later BTO, almost 400 individual House Sparrows were colour-ringed to allow their survival to be tracked through the winter. Blood and faecal samples were also collected from each individual, which were then screened for parasites and bacteria. The birds trapped and tested all originated from private gardens across 11 colonies scattered across London, where the House Sparrow population has fallen by 70% since 1995. Seven of these colonies had a negative population trend whilst four had a stable or increasing population. The results showed that the parasite Plasmodium relictum, which causes avian malaria, was found in 74% of House Sparrows, the highest prevalence recorded in populations of wild birds in Northern Europe. It was also found that the intensity of the infection (the number of parasites per individual bird) of avian malaria was correlated with negative population trends, especially in juvenile sparrows. Survival analyses on individual House Sparrows showed that birds with higher infection of malaria, whether juveniles or adults, had a lower probability of surviving the winter than did individuals with less severe infections. It was therefore concluded that avian malaria was linked to population decline through reduced overwinter survival of juveniles. It is unclear why avian malaria, which was likely native to the UK before the onset of the population decline of House Sparrows, may be affecting this species so significantly in London. House Sparrows are sedentary and BTO ringing data suggest that dispersal distances of this species have decreased from 1970 to 2010. It is possible that loss of habitat within cities might have led to isolated populations which are not very genetically diverse. This can result in a less-effective immune system and higher mortality, which, combined with low recruitment of new birds into the colonies, can lead to population decline. Whilst the underlying causes of House Sparrow declines remain unknown, and are likely due to a combination of factors, this study suggests that avian malaria may be implicated. Improved disease surveillance and continuing monitoring of the species at national level are essential for effective conservation management.

17.07.19

Papers

The composition of British bird communities is associated with long-term garden bird feeding

Author:

Published: 2019

Newly published research from BTO shows how the popular pastime of feeding the birds is significantly shaping garden bird communities in Britain. The populations of several species of garden birds have grown in number, and the diversity of species visiting feeders has also increased.

21.05.19

Papers

The risk of extinction for birds in Great Britain

Author:

Published: 2017

The UK has lost seven species of breeding birds in the last 200 years. Conservation efforts to prevent this from happening to other species, both in the UK and around the world, are guided by species’ priorities lists, which are often informed by data on range, population size and the degree of decline or increase in numbers. These are the sorts of data that BTO collects through its core surveys. For most taxonomic groups the priority list is provided by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) – the IUCN Red List comprises roughly 12,000 species worldwide and their conservation status. However, for birds in the UK, most policy makers refer to the Birds of Conservation Concern (BoCC) list, updated every six years (most recently in 2015). A new study funded by the RSPB and Natural England in cooperation with BTO, WWT, JNCC, and Game & Wildlife Trust has carried out the first IUCN assessment for birds in Great Britain. The study applied the IUCN criteria to existing bird population data obtained from datasets like the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey (BBS). The criteria take into account various factors, most notably any reduction in the size (both in abundance and range) of populations, loss of habitats key to the species, small or vulnerable population sizes, and extinction risk. Alongside this, the criteria look to see if there is a “rescue” effect – such as immigration from neighbouring populations that might boost the population’s numbers, reducing the risk of extinction. The species are then categorised into one of the threat levels below. The results of the new study show that a concerning 43% of regularly occurring species in Great Britain are classed as Threatened, with another 10% classified as Near Threatened. Twenty-three breeding or non-breeding populations of birds were classed as Critically Endangered, including Fieldfare and Golden Oriole (both possibly extinct as breeders), Whimbrel, Turtle Dove, Arctic Skua and Kittiwake, as well as non-breeding populations of Bewick’s Swan, White-fronted Goose and Smew., Over the past 200 years, seven species have gone extinct as breeders in Britain, including Serin, Temminck’s Stint and Wryneck in the past 25 years. The total percentage of threatened birds in Great Britain (43%) is high compared to that seen elsewhere in Europe (13%). Reasons for this are not entirely clear, although it may be that Britain’s island status has something to do with this, as there are fewer neighbouring “rescue” populations. Although the results from the IUCN assessment and BoCC assessment largely overlap, the IUCN assessment raises the level of concern for species such as Red-Breasted Merganser, Great Crested Grebe, Moorhen, Red-Billed Chough (all classed as Vulnerable), and Greenfinch (Endangered). These species might thus warrant closer monitoring in the near future. In contrast, the BoCC assessment identifies a number of species of concern whose declines have been more gradual but over long time periods (e.g. Skylark and House Sparrow). The authors emphasise that this assessment is not a replacement of the BoCC report, but rather that the two reports complement each other. With this new wealth of knowledge, there will hopefully be even more support for those species that need it most.

01.09.17

Papers

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).