Grey Partridge

Introduction

The 'English' Partridge, as it is sometimes known, is a resident and sedentary bird, associated with lowland farmland.

Grey Partridges are best seen in winter, when the fields are bare and the birds gather in small groups called 'coveys' to feed on seeds, roots and shoots. Their bodies form small mounds which can be mistaken for clods of earth, or even for Brown Hares which often share the same habitat.

Once widespread, the Grey Partridge is now Red-listed as a Bird of Conservation Concern in the UK due to steep population declines, which have been linked to agricultural intensification.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Partridges

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

This native gamebird has declined enormously and, despite years of research and the application of a government biodiversity action plan, the continuing decline shown by CBC/BBS suggests that all efforts to boost the population in the wider countryside have so far been unsuccessful. Grey Partridge is also declining in Europe (PECBMS), with steep declines in the 1980s and 1990s (Kuijper et al. 2009, PECBMS 2009) followed by a shallower decline subsequently (PECBMS 2020a>). Numbers can be artificially increased within shooting estates where nesting habitat can be provided and pesticide use restricted, but at the expense of corvids, mustelids and foxes (Sotherton et al. 2014).

Distribution

Grey Partridges are widespread across lowland England, except for the southeast and southwest. They occupy a wide strip along the east of Scotland but are now very scarce in the north and southwest. They are absent from most of Wales, except Anglesey and along the Welsh Marches.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Grey Partridge breeding range has declined by 46% since the 1968–72 Breeding Atlas, with losses initially in Ireland, Wales, southwest England and southwest Scotland, with more recent losses in southeast England, the west Midlands and on the western edge of the range in Scotland.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

Grey Partridges are recorded throughout the year.

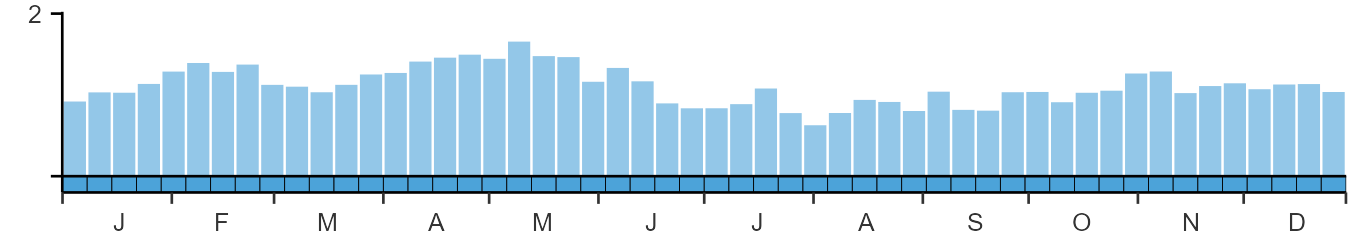

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

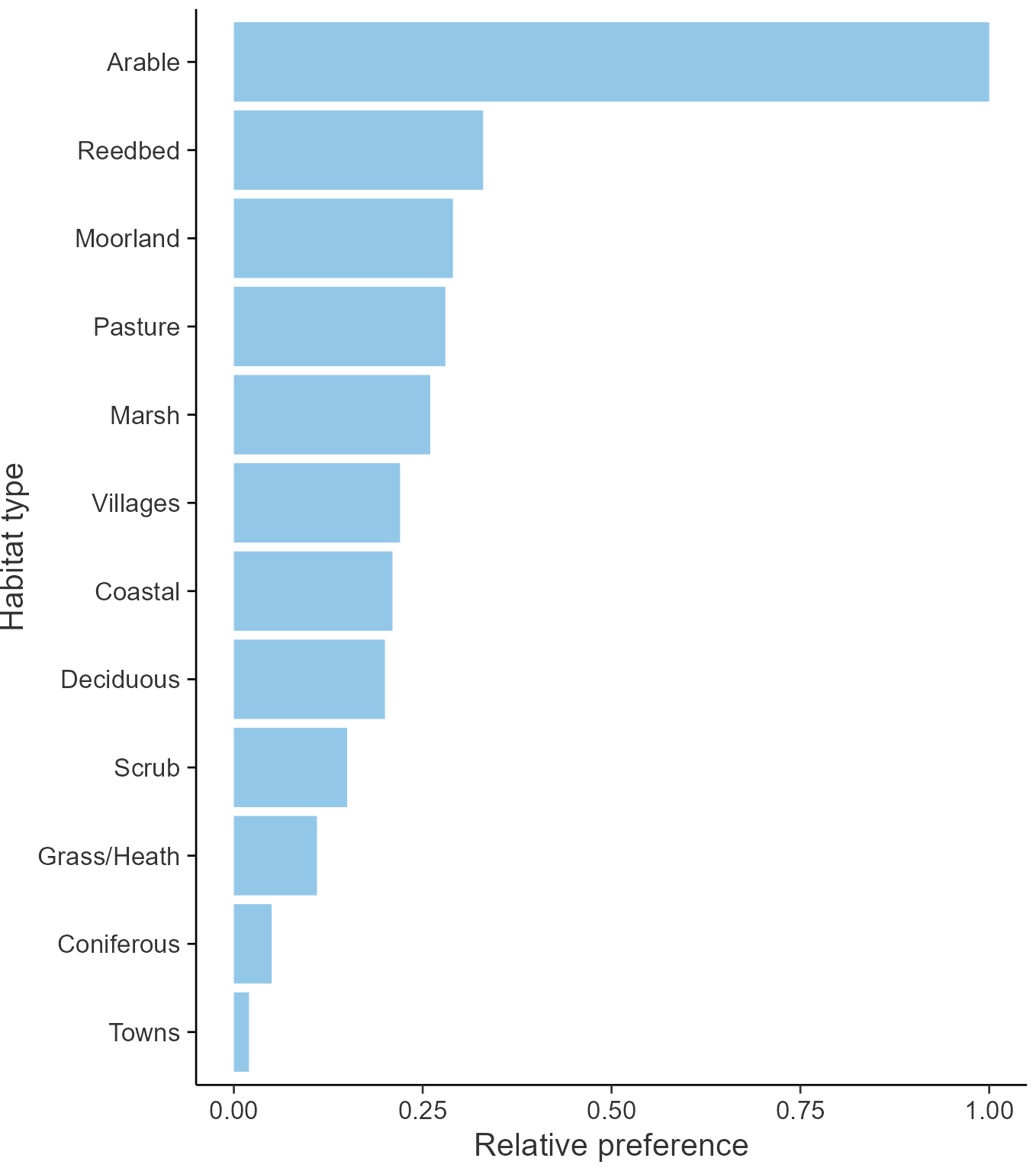

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Galliformes

- Family: Phasianidae

- Scientific name: Perdix perdix

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: P.

- BTO 5-letter code: GREPA

- Euring code number: 3670

Alternate species names

- Catalan: perdiu xerra

- Czech: koroptev polní

- Danish: Agerhøne

- Dutch: Patrijs

- Estonian: nurmkana

- Finnish: peltopyy

- French: Perdrix grise

- Gaelic: Cearc-thomain

- German: Rebhuhn

- Hungarian: fogoly

- Icelandic: Akurhæna

- Irish: Patraisc

- Italian: Starna

- Latvian: laukirbe

- Lithuanian: pilkoji kurapka

- Norwegian: Rapphøne

- Polish: kuropatwa (zwyczajna)

- Portuguese: charrela

- Slovak: jarabica polná

- Slovenian: jerebica

- Spanish: Perdiz pardilla

- Swedish: rapphöna

- Welsh: Petrisen

- English folkname(s): English Partridge

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The ultimate factor behind the decline is the deterioration of the bird's agricultural habitat. There is convincing evidence showing that a steep drop in chick survival rate as a result of decreasing chick food availability due to agricultural intensification is the primary driver of population declines. A reduction of hen survival rate during incubation, lower nest success and reduction of winter survival, related to increased predation rates, have all been reported as also playing secondary roles.

Further information on causes of change

Modelling suggests that climate change may have had a positive impact on the long-term trend for this species, resulting in less negative trends than would have occurred in the absence of climate change (Pearce-Higgins & Crick 2019). However, any such positive effect has clearly been minimal in comparison to the negative drivers of change.

The ultimate factor behind the decline of this species is the deterioration of the bird's agricultural habitat (Aebischer & Ewald 2004). A detailed field and modelling study in the 1980s provides excellent evidence relating to the ecology and population dynamics of the Grey Partridge in a large (62 sq km) study area in Sussex (Potts 1980, Potts 2012). Potts (1980, 2012) identified a reduction in chick survival during the first six weeks after hatching due to a herbicide-induced fall in cereal invertebrate abundance as the primary reason for the decline. More recently, the intensive use of broad-spectrum insecticides on cereals in the summer has been associated with a further reduction in average chick survival rate (Aebischer & Potts 1998). A field study involving an experimental set-up using sprayed and non-sprayed fields confirmed that invertebrate food supplies were important as it was shown that use of pesticides reduced food available to chicks, resulting in lower chick survival and thus depleting numbers of birds being recruited into the population (Rands 1985). Further support for this comes from Sotherton et al. (1993), who also both found that chick survival rate was lower in sprayed than in unsprayed areas. A tracking study found that breeding birds preferred unimproved rough grazing habitat on hill farms in north-east England. This habitat provided tall rushes as nesting cover and invertebrate food for chicks, especially sawfly larvae (Warren et al. 2017)

Potts also identified two other causes for the decline: the disappearance of nesting cover as field boundaries were removed to improve farming efficiency and lower brood production resulting from increased predation. There is evidence from various sources indicating that a reduction of hen survival rate during incubation, lower nest success and a reduction of winter survival, related to increased predation rates, have been influential in the continued population decrease from the 1970s (Potts & Aebischer 1995, Tapper et al. 1996, Bro et al. 2000, De Leo et al. 2004, Panek 2005).

Aebischer & Ewald (2010) offer convincing evidence that, since 2002, local Grey Partridge recoveries have been made possible by sympathetic management of rotational set-aside to provide cover for chicks. In an area of nearly 1,000 ha in Hertfordshire, set-aside was used for habitat creation and Grey Partridge breeding density increased sixfold. However, the disappearance of rotational set-aside in 2007, which halved the amount of brood-rearing habitat, with concurrent poor weather, reversed the increase and effectively removed this potential mechanism for national population recovery.

Overshooting due to the failure of hunters to separate Grey Partridges from Red-legs can have local population effects, but this is not likely to be a national problem (Aebischer & Ewald 2004). Aebischer & Ewald (2010) showed that on Partridge Count Scheme (PCS) sites, the annual change in spring density in recent years was not related to either shooting pressure or intensity of Red-legged Partridge releasing and suggest that provision of brood-rearing habitats and game cover increased with the latter, which probably counteracted the shooting losses of Grey Partridges on Red-legged Partridge shoots.

In some areas, parasite-mediated apparent competition with the Pheasant may be influencing the decline and subsequent recovery of wild Grey Partridges (Tompkins et al. 2000a, b). However, the evidence for this is conflicting, as Sage et al. (2002) found no deleterious fitness effects of the parasite and Browne et al. (2006) found that poor wild brood survival was indicative of low habitat and food quality rather than of a high rate of parasite infection. There is also evidence from a French study that Red-legged Partridges are dominant to Grey Partridges where they co-occur (Rinaud et al. 2020); however, there is no evidence yet to indicate that this may also be true in the UK and hence may have contributed to the UK declines.

Information about conservation actions

This species is well-studied and the conservation requirements are therefore fairly well understood. Research has shown that agricultural intensification is the main driver of declines and that, at a local level, the provision of nesting habitat and the reduction of pesticide-use can help increase productivity by increasing chick survival rates; hence actions such as the provision of conservation headlands, uncultivated margins, buffer strips and rotational set-aside, the sowing of wild bird seed mixtures to increase the proportion of natural or semi-natural vegetation, and reducing the area sprayed with herbicides will help improve and increase habitat for partridges (see Causes of Change section, above). Predator control may also help increase local populations (Tapper et al. 1996). Where this species occurs at Red-legged Partridge hunts, appropriate measures should be put in place to ensure accidental shooting of Grey Partridges is minimised and hence does not impact on local populations of the native species, as described by Aebischer & Ewald ( 2010).

Whilst such actions may help increase Grey Partridge numbers on individual farms (Aebischer & Ewald 2004; Newton 2004; Aebischer & Ewald 2010; Aebischer & Ewald 2010; Ewald et al. 2010), policies to encourage wider take up of the conservation actions described above may be needed in order to enable national populations to recover. Hence the inclusion of specific options in agri-environment schemes and payments to farmers for their provision may be required.

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).