Great Spotted Woodpecker

Introduction

With its striking black, white and red plumage, the Great Spotted Woodpecker's characteristic drumming display can be heard in woodlands across all but the most northerly regions of Britain. The species has a small but expanding range in Ireland.

Favouring deciduous woodland, the Great Spotted Woodpecker's primary food source is insects hidden under the bark in dead wood, but its diet also includes tree seeds and the eggs and young of other birds.

Great Spotted Woodpecker numbers have been increasing since the mid-20th century, and the species' breeding range has extended northwards across Scotland. A number of factors have been suggested as reasons for the increasing trend, including reduced competition for nestsites, greater availability of supplementary food at garden feeders, and an increase in the abundance of standing dead wood.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Great & Lesser Spotted Woodpeckers

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Alarm call:

Begging call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

This species increased rapidly in the 1970s and again in the late 1990s and 2000s. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that increase has been fairly uniform across the British range. A completely unexpected colonisation of Ireland, where there had previously been no resident woodpeckers, began in 2008, with genetic studies indicating Britain as the likely origin (Balmer et al. 2013). There has been an increase across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

Bird Atlas 2007–11 coincided with the colonisation of Ireland by Great Spotted Woodpeckers: breeding was first proved in Northern Ireland in 2006 and the Republic of Ireland in 2009. This species is undergoing a substantial range expansion in Britain too, most notably towards the north and west, with gains in occupancy evident in Scotland and Wales. The Northern Isles, Outer Hebrides and most of the Inner Hebrides remain unoccupied.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

The range expansion is in line with the rapid increase in population documented in the 1970s, with further increases from the early 1990s.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

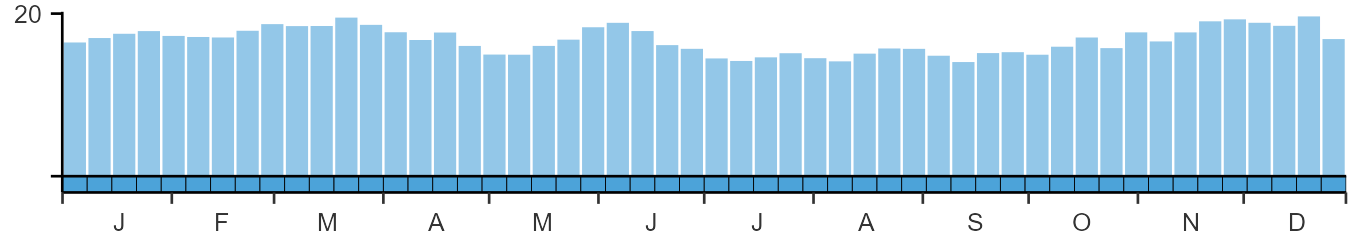

Great Spotted Woodpeckers are widely recorded throughout the year.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

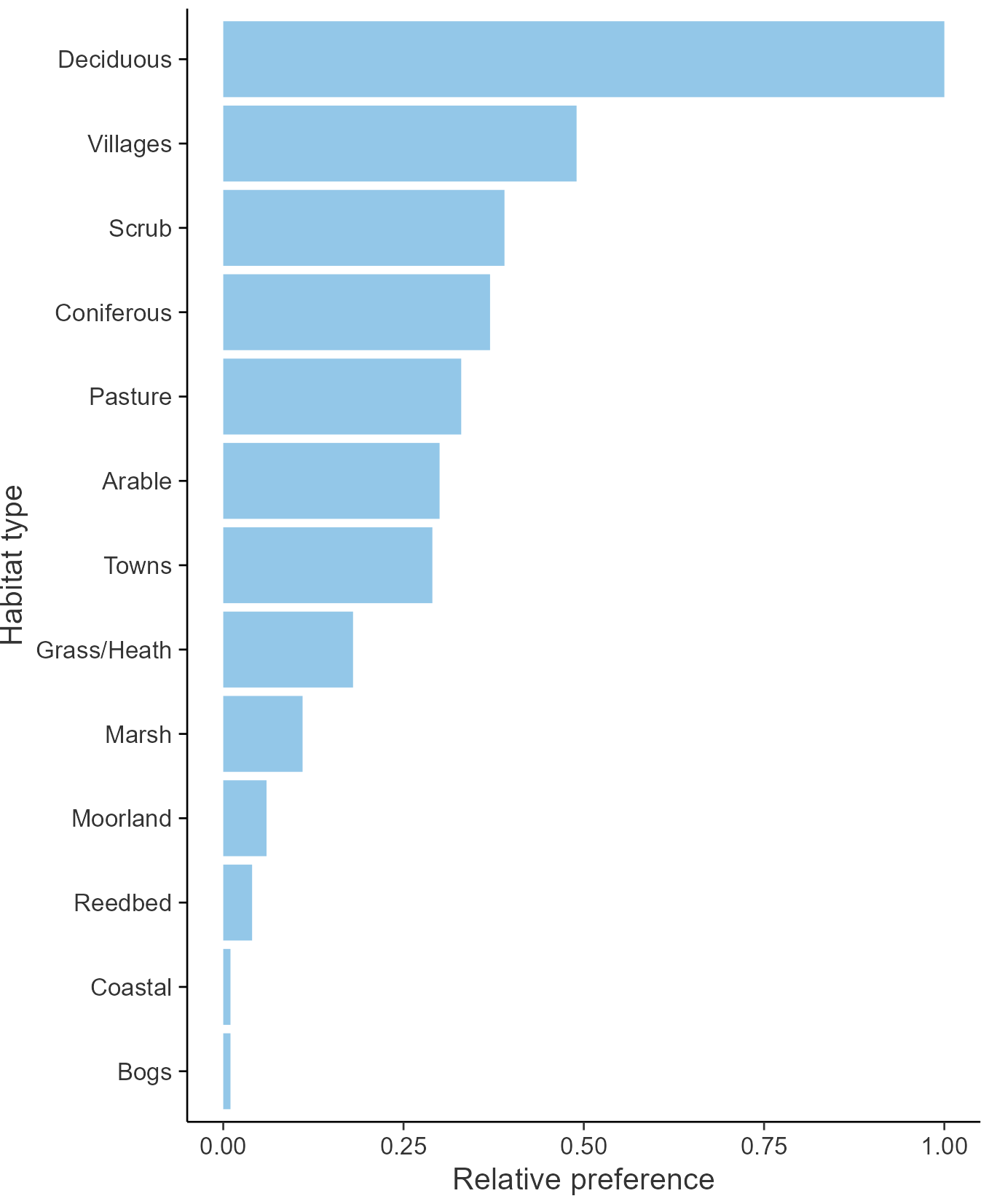

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Piciformes

- Family: Picidae

- Scientific name: Dendrocopos major

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: GS

- BTO 5-letter code: GRSWO

- Euring code number: 8760

Alternate species names

- Catalan: picot garser gros

- Czech: strakapoud velký

- Danish: Stor Flagspætte

- Dutch: Grote Bonte Specht

- Estonian: suur-kirjurähn

- Finnish: käpytikka

- French: Pic épeiche

- Gaelic: Snagan-daraich

- German: Buntspecht

- Hungarian: nagy fakopáncs

- Icelandic: Barrspæta

- Irish: Mórchnagaire Breac

- Italian: Picchio rosso maggiore

- Latvian: dižraibais dzenis

- Lithuanian: didysis margasis genys

- Norwegian: Flaggspett

- Polish: dzieciol duzy

- Portuguese: pica-pau-malhado-grande

- Slovak: datel velký

- Slovenian: veliki detel

- Spanish: Pico picapinos

- Swedish: större hackspett

- Welsh: Cnocell Fraith Fawr

- English folkname(s): Pied Woodpecker, Witwall

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There is good evidence that nest survival has increased, most likely due to decreased competition with Starlings. This is based on one local study but supported by more extensive analysis of nest record cards. Use of garden feeders may be another of many factors contributing to the population increase.

Further information on causes of change

The initial increase in Great Spotted Woodpeckers during the 1970s has been attributed to Dutch elm disease, which greatly increased the amount of standing dead timber, thereby increasing associated insects and so improving food supplies and providing nest sites (Marchant et al. 1990). However, studies giving demographic evidence supporting the effects of this are sparse. There has been speculation that the storms of 1987 and 1990 also benefited Great Spotted Woodpeckers by increasing the availability of dead wood, although a detailed study by Smith (1997), in two study woodlands, reported no specific link between woodpecker increase and the storms, despite the increase in dead wood.

A long-term study of the breeding success of an increasing population of Great Spotted Woodpeckers in southern England provides good evidence that nest survival has increased dramatically over the last 20 years (Smith 2005, 2006). Nest-site interference by Starlings was frequent during the 1980s and was described as the main cause of low nest survival and delayed nesting. Smith found that Starling numbers declined to such an extent later in the study that they ceased to nest in the study woods and nest-site interference was no longer a factor. Thus, the reduction in nest-site competition from Starlings is likely to be one of the factors contributing to the increase in Great Spotted Woodpeckers. Smith (2005) analysed national nest record cards and found similar trends in nest survival, supporting the hypothesis that reduced competition with Starlings has led to the increase in woodpecker population. The decline in Starling numbers in recent decades may also have allowed Great Spotted Woodpeckers to expand their breeding distribution into less-wooded habitats (Smith 2005). Great Spotted Woodpeckers appear limited in their ability to advance their breeding period to maintain synchrony with their natural prey and thus their ready use of garden feeders has the potential to increase breeding success (Smith & Smith 2013).

It is possible that recent increases of Great Spotted Woodpeckers, are also, at least in part, driven by changing climate (Fuller et al. 2005). In Scandinavia (Nilsson et al. 1992) and Bialowieza Forest, Poland (Wesolowski & Tomialojc 1986), breeding numbers were found to be related to the severity of the preceding winter and the availability of conifer seeds on which the birds then feed. No similar relationship has been found in Britain (Marchant et al. 1990), which is probably not surprising given our relatively mild winters (Smith 1997). Smith (2006) found no evidence that increasing spring temperatures impacted on clutch size, nesting success or number of young fledged. Smith & Smith (2019) found that caterpillar abundance influenced breeding productivity; however, although caterpillar abundance trends may be linked to temperature, they are apparently also cyclic and hence there is no evidence linking UK population trends to caterpillar numbers.

Information about conservation actions

This species is increasing in the UK and hence it is not a species of conservation concern and conservation actions are not currently required.

Woodland management, provided deadwood features are maintained, is likely to continue to provide foraging and nesting habitat for this species. This species has significantly increased its use of garden feeders (Plummer et al. 2019) and, in addition to improving survival, this could also benefit this species by increasing breeding success (Smith & Smith 2013).

Some concerns have been raised about the possible impact of increasing populations of Great Spotted Woodpeckers on other species through predation; however studies of Willow Tit suggest that predation by Great Spotted Woodpeckers has made little or no contribution to the decline of that species (Siriwardena 2004; Lewis et al. 2007). Where concerns occur, measures such as covering boxes in wire mesh (Mainwaring & Hartly 2008 Mainwaring & Hartly 2008) or changing nest box design (Kalinski et al. 2009) can reduce predation of nest boxes.

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).