Goshawk

Introduction

This large and powerful bird is easily overlooked, its presence most readily revealed during the early breeding season when individuals make display flights over their woodland territories.

The Goshawk was an extremely rare bird historically, and may even have been lost from our shores as a breeding species during the late 1800s. Increasing numbers of records from the 1960s have been linked to escaped or deliberately released captive birds, and it is from these beginnings that our current population originates.

Now a widespread bird across much of Wales and southern Scotland, other populations show a more discrete distribution, often centred on large expanses of forest or woodland – e.g. the New Forest, Thetford Forest. The species is the target of persecution, a factor that was implicated in its poor fortunes back in the 1800s.

Key Stats

Identification

Songs and Calls

Call:

Begging call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

This species was driven to extinction by the late 19th century, with the decline attributed to deforestation and persecution (Hollom 1957). The subsequent population is believed to have arisen from birds which have been deliberately or accidentally released by falconers from the 1960s and 1970s onwards (Marquiss & Newton 1982) with the numbers and range initially increasing very slowly and the distribution remaining patchy (Balmer et al. 2013). Rare Breeding Birds Panel data indicate that the Goshawk population has increased strongly across the UK over recent decades,with a mean of 712 breeding pairs reported for the five-year period 2015–2019; estimates from county recorders suggest a populaton of around 1,200+ pairs (Eaton et al. 2021).

Distribution

Goshawks are resident, leading to similar patterns of distribution and abundance between seasons. Outside Wales and the Borders, the distribution comprises a number of clusters of occupied 10-km squares. Many territories are associated with large state-owned forests.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

There have been significant range expansions in both seasons. Some may be due to better coverage and reporting, but there has undoubtedly been a concurrent population increase.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

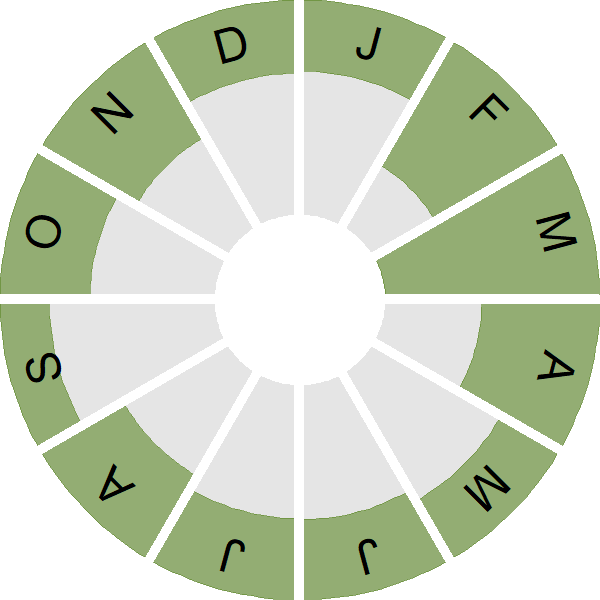

Seasonality

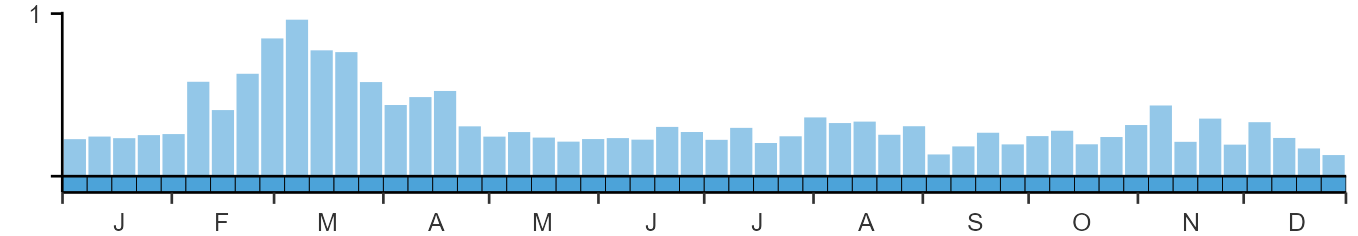

Goshawks are present year-round but recorded most often in late winter/early spring during spring aerial displays.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Accipitriformes

- Family: Accipitridae

- Scientific name: Astur gentilis

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: GI

- BTO 5-letter code: GOSHA

- Euring code number: 2670

Alternate species names

- Catalan: astor comú

- Czech: jestráb lesní

- Danish: Duehøg

- Dutch: Havik

- Estonian: kanakull

- Finnish: kanahaukka

- French: Autour des palombes

- Gaelic: Glas-sheabhag

- German: Habicht

- Hungarian: héja

- Icelandic: Gáshaukur

- Irish: Spioróg Mhór

- Italian: Astore

- Latvian: vistu vanags

- Lithuanian: paprastasis vištvanagis

- Norwegian: Hønsehauk

- Polish: jastrzab (zwyczajny)

- Portuguese: açor

- Slovak: jastrab velký

- Slovenian: kragulj

- Spanish: Azor común

- Swedish: duvhök

- Welsh: Gwalch Marth

- English folkname(s): Pigeon Hawk

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The UK population originates from birds deliberately or accidentally released by falconers during the 1960s and 1970s (Balmer et al. 2013). The localised pattern of such releases and high levels of illegal killing are believed to have influenced the patchy distribution of this species across the UK (Marquiss et al. 2003), as it is slow to disperse and colonise new breeding areas. Goshawks in the UK are often associated with large forests, often conifer plantations and this may influence their distribution in the UK, although some continental populations do breed in urban areas. Habitat quality and weather during the breeding season and in autumn were the most important drivers of population growth rate in a German population (Krüger & Lindström 2001); similar factors could be influencing the trend in the UK, but this should not be assumed as the range expansion of the UK population is ongoing and the relative importance of these factors and other factors may be different.

Publications (3)

Post-fledging movements in an elusive raptor, the Eurasian Goshawk Accipiter gentilis: scale of dispersal, foraging range and habitat interactions in lowland England

Author:

Published: 2025

GPS tracking of young Goshawks in lowland England reveals the movements and habitat use of this species, how these characteristics differ between the sexes, and how they change over the birds’ early lives. The UK Goshawk population is recovering from near extinction due to persecution in the early 20th century. Today, there are thought to be around 1,200 breeding pairs across the country, distributed patchily and at a low density. The population is likely below carrying capacity given the numbers present in neighbouring European countries, where the species is found in a variety of habitats including in cities. In the UK, the Goshawk is largely confined to forest habitats, but since the population is predicted to rise, this could change. An understanding of the movements and habitat requirements of this species could therefore help to understand how the species distribution might change in future. In this study, 29 GPS-GSM tags were fitted to Goshawk chicks at 22 nests in Breckland (Norfolk and Suffolk) and Gloucestershire. These solar powered tracking devices downloaded their data via the mobile phone network, revealing the young birds’ movements once they fledged and started to become independent. The results showed that young birds in their first winter settled on the periphery of their parents’ breeding habitat, and occupied a small range of approximately 5 km in diameter. These home ranges tended to be associated with mixed, open habitats by forest edges with farmland, or on farmland entirely. Male birds especially favoured farmland habitats. These habitat differences between the sexes might be determined by the prey types that smaller male birds can take, with suitable prey more available on farmland. As the young Goshawks matured, their habitats shifted towards the denser forests associated with their parents. The relatively short dispersal distances covered by young birds in this study indicates that a range expansion out of the species’ forest strongholds might take some time. However, young birds’ ability to take advantage of non-forest habitats does suggest that expansion is highly probable, especially if combined with a continued reduction in persecution and access to key prey.

14.03.25

Papers

Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4: the population status of birds in Wales

Author:

Published: 2022

The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List, with 91 on the Amber List and just 69 - less than a third of the total number of species - on the Green List. The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales comes 20 years after the first, when the Red List was less than half the length it is today. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List in Wales, with 91 on the Amber List and 69 on the Green List. The Birds of Conservation Concern in Wales report assesses the status of each species against a set of objective criteria. Data sources include the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey and the BTO/RSPB/JNCC Wetland Bird Survey, as well as Bird Atlases and other BTO-led monitoring schemes and citizen science initiatives. These are used to quantify the changing status of the species’ Welsh population. The UK, European and global conservation status of the species is also considered, placing the Welsh population into a wider context. The Red ListSwift, Greenfinch and Rook – familiar breeding species in steep decline across the UK – are among the new additions to the Welsh Red List, which now also includes Purple Sandpiper, on account of a rapidly shrinking Welsh wintering population, and Leach’s Petrel, an enigmatic seabird in decline across its global range. These species now sit alongside well-known conservation priorities, such as Curlew, Hen Harrier and Turtle Dove as birds at risk of being lost from Wales for good. Uplands and woodlands Many of the species on the Red List are found in upland and farmland habitats. Starling, Tree Sparrow, Yellow Wagtail and Yellowhammer can no longer be found in much of Wales, while iconic species of mountain and moorland, such as Ring Ouzel, Merlin and Black Grouse, remain in serious trouble. Wales is well known for its populations of woodland birds; however, many of these – including Lesser Spotted Woodpecker, Willow Warbler and Spotted Flycatcher – also feature on the Red List. Goldcrest, which has seen its Welsh population shrink alarmingly in recent decades, is another new addition. On the coast The assessment for Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4 took place before the impacts of avian influenza could be taken into account. Breeding seabird species have been struggling in Wales for many years, however, and most were already of conservation concern before the outbreak of this disease. Kittiwake, Puffin, Black-headed Gull, and Common, Arctic and Sandwich Tern remain on the Red List. Wales holds internationally significant numbers of breeding seabirds, making the decline of these colonies a global concern. The Amber ListDeclines in Wheatear, Garden Warbler and House Martin - all migrants which breed in Europe and winter in sub-Saharan Africa - mean these species have moved from the Green List to the Amber List. Many other ‘Afro-Palearctic' migrant species are also in decline, but the potential reasons for this, such as habitat loss and reduced availability of invertebrate prey, are not well understood. Closer to home, the declines in the Welsh Chaffinch population, linked to the disease trichomonosis, have seen the species Amber-listed. A number of other species have been placed on the Amber List because of the wider importance of their Welsh populations, which in each case make up more than half the UK total. Wales is home to more than three-quarters of the UK’s Choughs, for example, so recent declines are cause for concern. The nation’s breeding populations of Manx Shearwater, Pied Flycatcher, Goshawk and Hawfinch also account for more than half the UK total, as does its wintering population of Spotted Redshank. It’s not all bad news, though: some species now on the Amber List have moved up from the Red List, indicating some positive change in their population trends. These include Common Sandpiper, Great Black-backed Gull, Bullfinch, Goldcrest and Pied Flycatcher. The Green ListWhile the report contains much cause for alarm, several conservation success stories shine through. Red Kite was almost lost as a British bird during the first half of the 20th century, when only a handful of pairs remained in remote Welsh valleys. Since then, a sustained conservation effort has brought the species back from the brink. Wales is now home to more than 2,500 pairs of Red Kite and the species has now been moved to the Green List, reflecting this incredible change in fortunes. Song Thrush, Reed Bunting, Long-tailed Tit, Redwing and Kingfisher are among the other species to have gone Green, providing much-needed hope that things can go up as well as down.

06.12.22

Reports Birds of Conservation Concern

Exploring the lives of Goshawks in the Brecks: identifying patterns in nest behaviour, habitat use and movements within and beyond the Brecks

Author:

Published: 2017

01.07.17

Papers

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).