Dunlin

Introduction

The Dunlin's summer dress (chestnut back and black belly) is very distinctive, but in winter it has muted monochrome colours.

In summer the Dunlin breeds on grassland and moorland, often in company of Golden Plovers, earning it the nickname of 'Plover's Page'. In winter it is primarily coastal, where it is our most numerous small wader. Although its plumage is nondescript in winter, its long slightly curved bill helps identify it.

Ringing data show our breeding Dunlin mostly move south to Europe and North Africa in winter; our wintering birds primarily come from eastern Europe and Russia. WeBS counts show that wintering individuals are visiting in decreasing numbers, as climate change means the winter conditions around the Baltic become increasingly less severe.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Knot and Dunlin

Songs and Calls

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Dunlin is a widespread visitor around most of the coast of the UK in winter, present in very large numbers on some estuaries. It has a more restricted distribution as a breeding species in upland areas and in north and west Scotland. The status of Dunlin as a breeding species is uncertain. UK population estimates have been suggest stability with estimates of 9,150–9,900 in the 1980s (Stone et al. 1997) and 8,600–10,500 in 2005–07 (Musgrove et al. 2013). The 2005–07 estimate was repeated in the most recent assessment (APEP4). However, there is evidence from two other sources that declines may have occurred. A survey of nine upland study areas in 2000 and 2002 which re-surveyed sites visited between 1980 and 1991, found that Dunlin had significantly declined in two of the seven study areas for which results for Dunlin could be produced, with no significant increases (Sim et al. 2005). Elsewhere, the population on the machair in the Outer Hebrides, which formerly supported a quarter of the British population, dropped by 50% between 1983 and 2000 and by a further 15% by 2007 (Fuller et al. 2010).

Distribution

Wintering Dunlins are widely distributed around the coastlines of Britain and Ireland, with the exception of steep rocky shores, as predominate in western Scotland. They also occur regularly in small numbers at inland sites, especially in England. Strongholds for breeding Dunlin are all in Scotland, in the Northern Isles and Outer Hebrides, the flow country of Caithness and Sutherland, the hills of the northwest Highlands and the Grampian Mountains. Further south, good numbers remain in the Pennines, but only a few pairs are to be found in the Southern Uplands, in central Wales and on Dartmoor.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

The Dunlin's winter distribution has changed little since the 1980s whereas the breeding range shows losses in marginal upland areas, particularly in western Ireland, northern England and southern Scotland.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

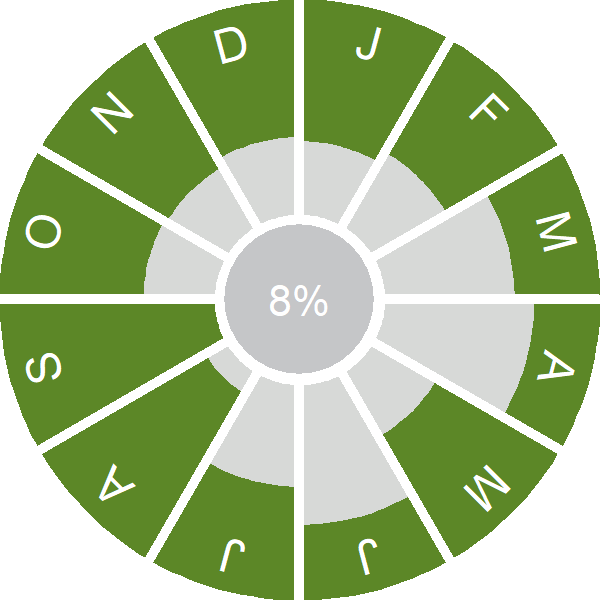

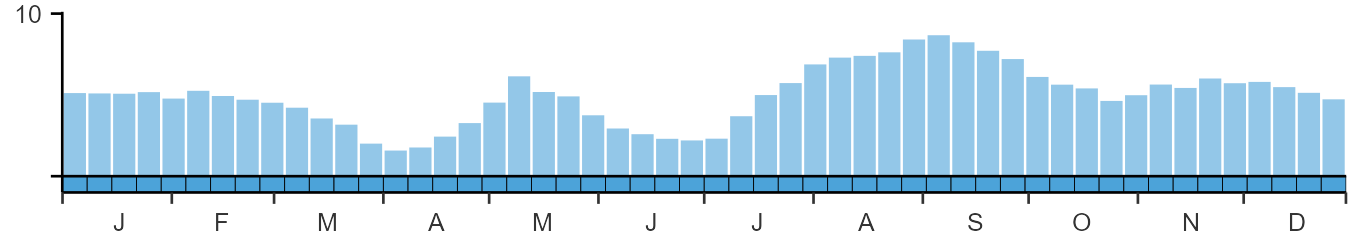

Seasonality

Dunlins are recorded throughout the year with strong cycles of detection associated with pulses of migration as different wintering and breeding populations move through the UK.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Charadriiformes

- Family: Scolopacidae

- Scientific name: Calidris alpina

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: DN

- BTO 5-letter code: DUNLI

- Euring code number: 5120

Alternate species names

- Catalan: territ variant

- Czech: jespák obecný

- Danish: Almindelig Ryle

- Dutch: Bonte Strandloper

- Estonian: soorüdi e. soorisla

- Finnish: suosirri

- French: Bécasseau variable

- Gaelic: Gille-feadaig

- German: Alpenstrandläufer

- Hungarian: havasi partfutó

- Icelandic: Lóuþræll

- Irish: Breacóg

- Italian: Piovanello pancianera

- Latvian: parastais šnibitis

- Lithuanian: juodakrutis begikas

- Norwegian: Myrsnipe

- Polish: biegus zmienny

- Portuguese: pilrito-de-peito-preto

- Slovak: pobrežník ciernozobý

- Slovenian: spremenljivi prodnik

- Spanish: Correlimos común

- Swedish: kärrsnäppa

- Welsh: Pibydd Mawn

- English folkname(s): Plover's Page, Tang Snipe

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

In the Hebrides, predation by introduced hedgehogs has been a driver of declines (Jackson & Green 2000). Habitat loss is believed to have caused declines elsewhere, in particular the planting of forestry on moorland (Lavers & Haines-Young 1997).

Publications (8)

Waterbirds in the UK 2022/23

Author:

Published: Winter 2024

It provides a single, comprehensive source of information on the current status and distribution of waterbirds in the UK for those interested in the conservation of the populations of these species and the wetland sites they use. Data from this edition of Waterbirds in the UK provide further evidence that wintering ducks, geese, swans and waders are adapting to climate change by altering their migration.

25.04.24

Reports Waterbirds in the UK

Changes in breeding wader populations of the Uist machair and adjacent habitats between 1983 and 2022

Author:

Published: 2023

Periodic surveys of machair and associated habitats on the west coast of North Uist, Benbecula and South Uist have documented marked changes in the composition of an important breeding wader assemblage. Within the study area of there was a 25% decline in the total number of breeding waders recorded between 1983 and 2022.

15.06.23

Papers

How important is it to standardise the measured mass of shorebirds weighed at varying intervals after capture?

Author:

Published: 2023

When ringing birds it is usually important to standardise measurements so that sources of error are minimised. For example, trainee ringers are taught how to measure wing lengths in the most repeatable fashion. Measuring bird weight is usually much more straightforward. One situation where this may not be the case is during canon netting when large numbers of birds can be caught at once, but are weighed gradually as the birds are processed, potentially leading to biases. This paper examines this phenomenon using captures of Knot, Turnstone, Dunlin and Semipalmated Sandpiper in Delaware Bay, USA. As these waders were caught whilst actively feeding on the eggs of Horseshoe Crabs, there was the possibility that birds weighed first could be heavier due to having a gut full of eggs, whilst those weighed last may have digested/voided their gut contents prior to being weighed and so weigh relatively less. For sample bird catches birds were weighed repeatedly, from immediately after capture to up to four hours after capture. The study found that birds rapidly lost up to 5% of their body weight in the first 30 minutes, with weight loss much reduced thereafter. This weight loss was strongly correlated to the number of droppings birds produced in the keeping pens, indicating the reduction was related to processing of gut contents. The paper shows how body weights can be standardised to that expected if each bird was weighed at 30 minutes after capture. For large catches this can increase the apparent mean weight for the sample by up to 2%. The paper also discusses the situations in which standardising body weight measurements for time from capture may be necessary.

01.04.23

Papers

Sensitivity mapping for breeding waders in Britain: towards producing zonal maps to guide wader conservation, forest expansion and other land-use changes. Report with specific data for Northumberland and north-east Cumbria

Author:

Published: 2021

Breeding waders in Britain are high profile species of conservation concern because of their declining populations and the international significance of some of their populations. Forest expansion is one of the most important, ongoing and large-scale changes in land use that can provide conservation and wider environmental benefits, but also adversely affect populations of breeding waders. We describe models to be used towards the development of tools to guide, inform and minimise conflict between wader conservation and forest expansion. Extensive data on breeding wader occurrence is typically available at spatial scales that are too coarse to best inform waderconservation and forestry stakeholders. Using statistical models (random forest regression trees) we model the predicted relative abundances of 10 species of breeding wader across Britain at 1-km square resolution. Bird data are taken from Bird Atlas 2007–11, which was a joint project between BTO, BirdWatch Ireland and the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club, and modelled with a range of environmental data sets.

09.12.21

BTO Research Reports

The status of our bird populations: the fifth Birds of Conservation Concern in the United Kingdom, Channel Islands and Isle of Man and second IUCN Red List assessment of extinction risk for Great Britain

Author:

Published: 2021

Commonly referred to as the UK Red List for birds, this is the fifth review of the status of birds in the UK, Channel Islands and Isle of Man, published in December 2021 as Birds of Conservation Concern 5 (BOCC5). This updates the last assessment in 2015. Using standardised criteria, experts from a range of bird NGOs, including BTO, assessed 245 species with breeding, passage or wintering populations in the UK and assigned each to the Red, Amber or Green Lists of conservation concern. The same group of experts undertook a parallel exercise to assess the extinction risk of all bird species for Great Britain (the geographical area at which all other taxa are assessed) using the criteria and protocols established globally by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). This resulted in the assessment of 235 regularly occurring species (breeding or wintering or both), the total number assessed differing slightly from BOCC5 due to different rules on the inclusion of scarce breeders and colonisation patterns. The results of this second IUCN assessment (IUCN2) are provided in the same paper as BOCC5. Increasingly at risk This update shows that the UK’s bird species are increasingly at risk, with the Red List growing from 67 to 70. Eleven species were Red-listed for the first time, six due to worsening declines in breeding populations (Greenfinch, Swift, House Martin, Ptarmigan, Purple Sandpiper and Montagu’s Harrier), four due to worsening declines in non-breeding wintering populations (Bewick’s Swan, Goldeneye, Smew and Dunlin) and one (Leach’s Storm-petrel) because it is assessed according to IUCN criteria as Globally Vulnerable, and due to evidence of severe declines since 2000 based on new surveys on St Kilda, which holds more than 90% of the UK’s populations. The evidence for the changes in the other species come from the UK’s key monitoring schemes such as BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) for terrestrial birds, the BTO/RSPB/JNCC Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS) for wintering populations and the Rare Breeding Bird Panel (RBBP) for scarce breeding species such as Purple Sandpiper. The IUCN assessment resulted in 108 (46%) of regularly occurring species being assessed as threatened with extinction in Great Britain, meaning that their population status was classed as Critically Endangered, Endangered, or Vulnerable, as opposed to Near Threatened or of Least Concern. Of those 108 species, 21 were considered Critically Endangered, 41 Endangered and 46 Vulnerable. There is considerable overlap between the lists but unlike the Red List in BOCC5, IUCN2 highlights the vulnerability of some stable but small and hence vulnerable populations as well as declines in species over much shorter recent time periods, as seen for Chaffinch and Swallow.

01.12.21

Reports Birds of Conservation Concern

Long term changes in the abundance of benthic foraging birds in a restored wetland

Author:

Published: 2021

10.09.21

Papers

Consequences of population change for local abundance and site occupancy of wintering waterbirds

Author:

Published: 2017

Protected sites for birds are typically designated based on the site’s importance for the species that use it. For example, sites may be selected as Special Protection Areas (under the European Union Directive on the Conservation of Wild Birds) if they support more than 1% of a given national or international population of a species or an assemblage of over 20,000 waterbirds or seabirds. However, through the impacts of changing climates, habitat loss and invasive species, the way species use sites may change. As populations increase, abundance at existing sites may go up or new sites may be colonized. Similarly, as populations decrease, abundance at occupied sites may go down, or some sites may be abandoned. Determining how bird populations are spread across protected sites, and how changes in populations may affect this, is essential to making sure that they remain protected in the future. These findings come from a new study by Verónica Méndez and colleagues from the University of East Anglia working with BTO. Using Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS) data the study looked at changes in the population sizes and distributions of 19 waterbird species across Britain during a period of 26 years and their effect on local abundance and site occupancy. Some of these species saw steady increases in population size (up to 1,600%, Avocet), whereas other saw mild declines (-26%, Purple Sandpiper and Shelduck). The results showed that changes in total population size were predominantly reflected in changes in local abundance, rather than through the addition or loss of sites. This is possibly because waterbirds tend to be long-lived birds, with high site fidelity and new suitable sites may not always be available. Thus colonisation of new sites may typically occur when their existing sites approach their maximum capacity. As changes in populations are largely manifested by changes in local abundance – and as sites are often designated for many species – the numbers of sites qualifying for site designation are unlikely to be affected. Understanding the dynamic between population change and change in local abundance will be key to ensuring the efficiency of protected area management and ensuring that populations are adequately protected. Data from the Wetland Bird Survey and its predecessor schemes, which are celebrating 70 years of continuous monitoring of waterbirds this year, have been integral to both the designation of protected sites and monitoring of their condition. Continuation of this monitoring through future generations will ensure that the impacts to waterbird populations of future environmental changes may be understood.

20.09.17

Papers

Methods for comparing low-tide trends for Wetland Bird Survey count sectors with wider regions: a pilot study for three wader species on the Stour and Orwell Estuaries SPA

Author:

Published: 2009

This report documents analysis of Wetland Bird Survey data for the Stour and Orwell SPA, identifying changes in counts over a 10-year period for Knot, Dunlin and Black-tailed Godwit. Through this, it shows the value of the SPA for these species.

01.01.09

BTO Research Reports

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).