Common Tern

Introduction

This summer visitor to Britain & Ireland is the most familiar of our terns thanks to its habit of inland nesting, a behaviour common across part of its wider range but absent in the larger Scottish colonies.

Common Terns arrive from the middle of April, departing again in late summer for wintering grounds that stretch south from the coast of Spain and around Africa's western seaboard.

While the Common Tern's British breeding range has expanded over recent years – thanks to birds occupying inland waterbodies such as flooded gravel bits – these inland colonies tend to be small, and the gains here contrast with losses at the larger coastal colonies.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Tern Identification Workshop Part 1: Common and Arctic Tern

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Flight call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Common Terns breed at lakes and reservoirs scattered across lowland Britain, especially in the major river valleys, and extensively at the coast. There are a few very large coastal colonies and groups of colonies that account for more than half the total population. Breeding numbers and productivity at sample colonies have been monitored annually since 1986 by JNCC's Seabird Monitoring Programme. The abundance trend shows approximate stability from 1986 to 2018 with some small fluctuations, equating to a 9% increase over this period (although this is not statistically significant), while productivity has fluctuated but appears to show a recent decline (SMP data here).

Common Terns are poorly covered by general breeding bird surveys because of their highly aggregated breeding population. There have been enough birds seen on BBS visits for a trend to be drawn but this has an exceptionally wide confidence interval and probably relates mainly to birds seen on overland passage, prospecting for nest sites or breeding in small, dispersed colonies. Extraordinary counts in 2017 and very high counts in 2014 have caused an upturn in the BBS index, but other recent counts have been similar to those from previous years.

Distribution

Breeding Common Terns are widespread and primarily coastal in Scotland and are found on the lochs and islands of the west coast, Outer Hebrides, Northern Isles and around the inner Moray Firth. This contrasts with England, where the species' range is dominated by inland colonies. In Ireland, colonies are more clustered, both on the coast and inland where most nest on islands in the largest lakes.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

The breeding distribution change map shows a clear pattern of losses in Scotland and Ireland contrasting with gains in eastern and central England since both previous breeding atlases.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

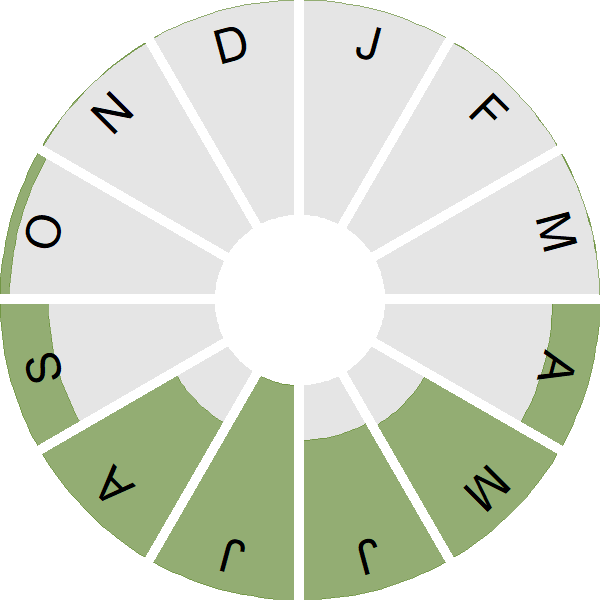

Seasonality

Common Tern is a summer breeding species, present from April onwards, departing from August onwards.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

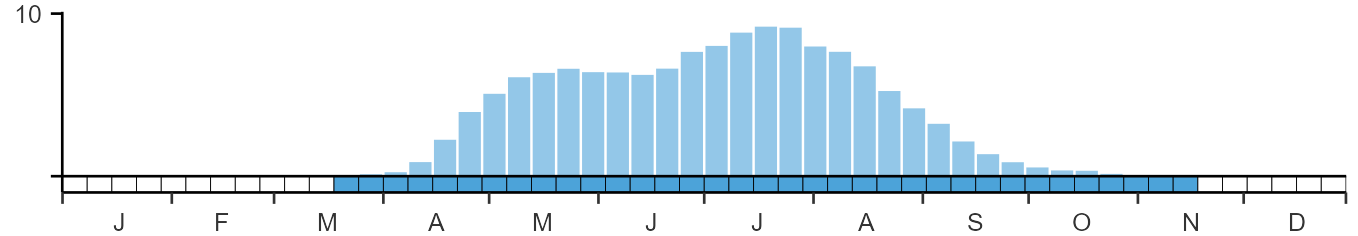

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Charadriiformes

- Family: Laridae

- Scientific name: Sterna hirundo

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: CN

- BTO 5-letter code: COMTE

- Euring code number: 6150

Alternate species names

- Catalan: xatrac comú

- Czech: rybák obecný

- Danish: Fjordterne

- Dutch: Visdief

- Estonian: jõgitiir

- Finnish: kalatiira

- French: Sterne pierregarin

- Gaelic: Steàrnag-chumanta

- German: Flussseeschwalbe

- Hungarian: küszvágó csér

- Icelandic: Sílaþerna

- Irish: Geabhróg

- Italian: Sterna comune

- Latvian: upes zirinš

- Lithuanian: upine žuvedra

- Norwegian: Makrellterne

- Polish: rybitwa rzeczna

- Portuguese: trinta-réis-boreal / gaivina

- Slovak: rybár riecny

- Slovenian: navadna cigra

- Spanish: Charrán común

- Swedish: fisktärna

- Welsh: Môr-wennol Gyffredin

- English folkname(s): Sea Swallow, Darr, Tirrick

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There is little good evidence available regarding the drivers of the breeding population change in this species in the UK.

Further information on causes of change

No further information is available.

Information about conservation actions

The reasons for the declines at coastal colonies are not clear and a wide range of potential conservation actions have been suggested by different authors. These include the control of predators such as rats (Amaral et al. 2010) and gulls (Blokpoel et al. 1997), including selectively controlling chick-predating gulls in Canada (Guillemette & Brousseau 2001); providing plywood shelters for chicks to reduce predation (Burgess & Morris 1992); actions to reduce disturbance such as restricting access to nesting areas (Fasola & Canova 1996) and educating watercraft owners about the effects of disturbance (Burger & Leonard 2000); and habitat management to reduce vegetation (Cook-Haley & Millenbah 2002). In the latter study, vegetation was reduced through spraying and nest success was highest in areas with moderate amounts (40-50%) of vegetation cover.

In Maryland, USA, McGowan et al. (2019) successfully relocated a colony affected by construction work to a new site 200 m away, using a combination of deterrents (overhead lines) at the old site and attractants (audio calls and decoys) at the new site. However, they caution that this approach should only be used when absolutely essential and note that whilst in this case there were no apparent effects on reproduction, this approach may not be viable on all sites.

It is currently unclear which action or actions are most likely to help reverse declines and hence further research may be needed to inform conservation policies. Denac & Bozic (2020) give an account of a wide variety of conservation measures undertaken to provide and enhance breeding habitat for Common Terns in Slovenia, including various actions to manage vegetation, reduce predation and increase nest site availability by preventing Black-headed Gulls from occupying sites (the latter by blocking access until terns had returned using a grid of plastic strings), The success (or failure) of the conservation actions are discussed, although this is largely subjective and the efficacy of the various measures have not been tested experimentally.

Away from coastal sites, the provision of nesting rafts has proved a successful method to attract Common Terns to previously unoccupied inland sites (Dunlop et al. 1991).

Publications (6)

Desk-based revision of seabird foraging ranges used for HRA screening

Author:

Published: 2019

A key step in understanding the possible impacts of a proposed windfarm development is to identify potential interactions between seabird breeding colonies and the proposed development areas. Such interactions are typically assessed using generic information on foraging ranges, derived from academic studies. This report uses the latest data to provide updated estimates of foraging range, which will help to ensure that the best available information is available when new developments are being considered.

01.12.19

BTO Research Reports

The status of the UK’s breeding seabirds

Author:

Published: 2024

Five seabird species are added to the Birds of Conservation Concern Red List in this addendum to the 2021 update, bringing the total number of Red-listed seabird species to 10, up from six since seabirds were last assessed. The Amber List of seabirds moves from 19 to 14 species, and the Green List increases from one to two species.

29.09.24

Papers

Seabird Population Trends and Causes of Change: 1986–2023

Author:

Published: 2024

This report presents the latest seabird population trends in breeding abundance and productivity using data from the Seabird Monitoring Programme (SMP).The report documents changes in the abundance and productivity of breeding seabird species in Britain and Ireland from 1986 to 2023, and provides a detailed account of the 2021, 2022 and 2023 breeding seasons. This report includes both inland and coastal populations and trends from the Channel Islands, England, Isle of Man, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales and the Republic of Ireland, which are presented where sufficient data are available. The results from this report are used more broadly to assess the health of the wider environment, to inform policy and for conservation action.

21.11.24

Reports SMP Report

Northern Ireland Seabird Report 2023

Author:

Published: 2024

The report includes detailed information about the population trends and breeding success of seabirds in Northern Ireland, over the 2023 breeding season. Notably, Fulmar and Kittiwake populations are reported to be experiencing continued declines, while Guillemot, Common Gull and Herring Gull populations show increases at most breeding sites. Low productivity was reported in Black-headed Gulls, Sandwich Terns and Common Terns, likely due to the impacts of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). Although Black-headed Gulls make up the majority of confirmed HPAI mortality cases in Northern Ireland in 2023, other birds significantly affected include terns, Kittiwakes and auks. A contributor report about HPAI in Northern Ireland by Ronan Owens (Higher Scientific Officer, DAERA, NIEA) details developments in environmental organisations’ responses to HPAI in 2023, including cross-sector communication, improved surveillance and monitoring of HPAI impacts, and improved online systems for the public to report dead birds. Monitoring reports for Strangford Lough and the Outer Ards are included, as well as several additional contributor articles: Copeland gull censuses, by Roisin Kearney (Assistant Conservation Officer, RSPB). The Copeland Islands host one of the largest mixed gull colonies in Northern Ireland, with significant numbers of Lesser Black-backed Gulls and Herring Gulls. The annual gull census was established in 2018; the article details the refinement of the methodology to date as well as the census results so far. Manx Shearwater tracking, by Patrick Lewin (DPhil Student, OxNav, Dept. of Biology, University of Oxford). Tracking the Manx Shearwaters that breed on Lighthouse Island (one of the three Copeland Islands) began in 2007. The article describes the history of tracking Manx Shearwaters from Copeland, including recent advances in technology that have allowed the tracking of fledgling birds as well as adults of breeding age, and the impact of this research on the conservation of shearwaters. Puffin surveys on Rathlin, by Ric Else (Life RAFT Senior Research Assistant, RSPB). Rathlin Island hosts Northern Ireland’s largest seabird colony. The response of seabirds to the removal of introduced Ferrets and Brown Rats from Rathlin is currently being monitored, with a particular focus on Puffins. These birds are especially vulnerable to mammalian predators because of their burrow nests. The article describes the challenges associated with calculating a population estimate, monitoring productivity and mapping the distribution of this species, and how these are being addressed in seabird surveys on Rathlin.

15.04.24

Reports Northern Ireland Seabird Report

Seabird abundances projected to decline in response to climate change in Britain and Ireland

Author:

Published: 2023

Britain and Ireland support globally-important numbers of breeding seabirds, but these populations are under pressure from a suite of threats, including marine pollution, habitat loss, overfishing and highly pathogenic avian influenza. Climate change introduces additional threats, the magnitude of which is uncertain in the future, making it difficult to plan how to apportion conservation efforts between seabird species. Predicting how species’ numbers could change under different climate change scenarios helps clarify their future vulnerability to extinction, and thus assists in conservation planning.

05.12.23

Papers

Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4: the population status of birds in Wales

Author:

Published: 2022

The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List, with 91 on the Amber List and just 69 - less than a third of the total number of species - on the Green List. The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales comes 20 years after the first, when the Red List was less than half the length it is today. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List in Wales, with 91 on the Amber List and 69 on the Green List. The Birds of Conservation Concern in Wales report assesses the status of each species against a set of objective criteria. Data sources include the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey and the BTO/RSPB/JNCC Wetland Bird Survey, as well as Bird Atlases and other BTO-led monitoring schemes and citizen science initiatives. These are used to quantify the changing status of the species’ Welsh population. The UK, European and global conservation status of the species is also considered, placing the Welsh population into a wider context. The Red ListSwift, Greenfinch and Rook – familiar breeding species in steep decline across the UK – are among the new additions to the Welsh Red List, which now also includes Purple Sandpiper, on account of a rapidly shrinking Welsh wintering population, and Leach’s Petrel, an enigmatic seabird in decline across its global range. These species now sit alongside well-known conservation priorities, such as Curlew, Hen Harrier and Turtle Dove as birds at risk of being lost from Wales for good. Uplands and woodlands Many of the species on the Red List are found in upland and farmland habitats. Starling, Tree Sparrow, Yellow Wagtail and Yellowhammer can no longer be found in much of Wales, while iconic species of mountain and moorland, such as Ring Ouzel, Merlin and Black Grouse, remain in serious trouble. Wales is well known for its populations of woodland birds; however, many of these – including Lesser Spotted Woodpecker, Willow Warbler and Spotted Flycatcher – also feature on the Red List. Goldcrest, which has seen its Welsh population shrink alarmingly in recent decades, is another new addition. On the coast The assessment for Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4 took place before the impacts of avian influenza could be taken into account. Breeding seabird species have been struggling in Wales for many years, however, and most were already of conservation concern before the outbreak of this disease. Kittiwake, Puffin, Black-headed Gull, and Common, Arctic and Sandwich Tern remain on the Red List. Wales holds internationally significant numbers of breeding seabirds, making the decline of these colonies a global concern. The Amber ListDeclines in Wheatear, Garden Warbler and House Martin - all migrants which breed in Europe and winter in sub-Saharan Africa - mean these species have moved from the Green List to the Amber List. Many other ‘Afro-Palearctic' migrant species are also in decline, but the potential reasons for this, such as habitat loss and reduced availability of invertebrate prey, are not well understood. Closer to home, the declines in the Welsh Chaffinch population, linked to the disease trichomonosis, have seen the species Amber-listed. A number of other species have been placed on the Amber List because of the wider importance of their Welsh populations, which in each case make up more than half the UK total. Wales is home to more than three-quarters of the UK’s Choughs, for example, so recent declines are cause for concern. The nation’s breeding populations of Manx Shearwater, Pied Flycatcher, Goshawk and Hawfinch also account for more than half the UK total, as does its wintering population of Spotted Redshank. It’s not all bad news, though: some species now on the Amber List have moved up from the Red List, indicating some positive change in their population trends. These include Common Sandpiper, Great Black-backed Gull, Bullfinch, Goldcrest and Pied Flycatcher. The Green ListWhile the report contains much cause for alarm, several conservation success stories shine through. Red Kite was almost lost as a British bird during the first half of the 20th century, when only a handful of pairs remained in remote Welsh valleys. Since then, a sustained conservation effort has brought the species back from the brink. Wales is now home to more than 2,500 pairs of Red Kite and the species has now been moved to the Green List, reflecting this incredible change in fortunes. Song Thrush, Reed Bunting, Long-tailed Tit, Redwing and Kingfisher are among the other species to have gone Green, providing much-needed hope that things can go up as well as down.

06.12.22

Reports Birds of Conservation Concern

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).