BirdTrack migration blog (29 September–5 October)

Over 50 individuals of some 15 species were reported over the course of the week. These included a new species for Britain in the form of a Canada Warbler in Pembrokeshire. There was also a Tennessee Warbler at Inishbofin, which was only the second record for Ireland. Other notable species included the second Bay-breasted Warbler and Philadelphia Vireo records for Britain, the third and fourth Magnolia Warbler records, and a Blackburnian Warbler in Shetland – the second record for the archipelago – and, on the Isles of Scilly, the first Northern Parula reported in Britain since 2010. Amazingly, three of the four Black-and-white Warblers reported were found on Bardsey Island, around Bardsey Bird and Field Observatory. The birds were all caught safely, ringed and released, so we can be sure there were three individuals.

This autumn will, without doubt, go down in birding folklore and be talked about for years to come. Whether you saw any of these birds or not, the sheer number, variety, and intensity of the past week from a birdwatching perspective is truly staggering.

The run of westerly winds also saw the numbers of common migrants build as birds congregated near the coast, waiting for the winds to drop or change direction before continuing migration. Both Blackcaps and Chiffchaffs continued to be seen in good numbers; it seemed every stretch of hedge or scrub hosted a Chiffchaff in some areas, with many birds still singing. These birds probably moved on as the wind began to drop in the south and east during the later part of the week, but were likely replaced by birds from further north, which will continue to filter down the UK in the next couple of weeks.

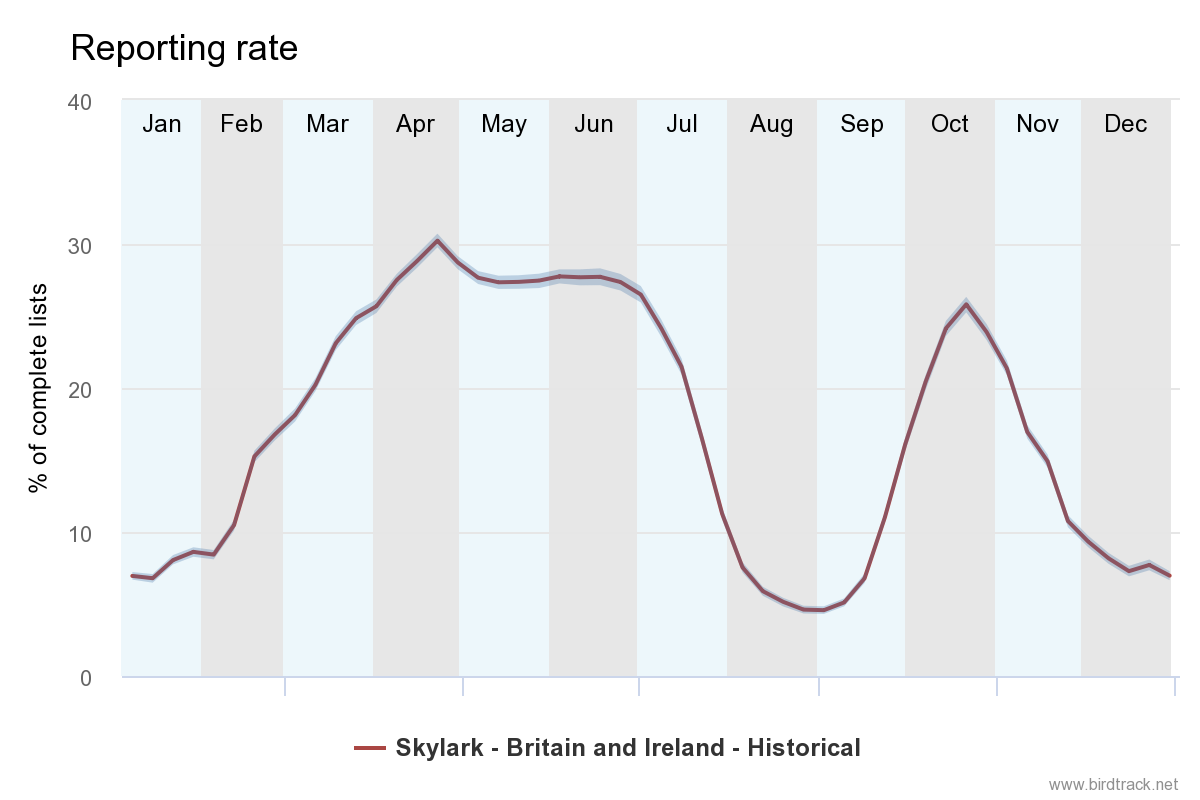

Each August, reports of Skylark fall away; when the birds stop singing they become less obvious and harder to find. However, as autumn progresses, we see reports increase again as birds disperse away from their breeding areas. Last week saw the first push of these birds as they took advantage of the clear skies and a drop in the wind, with small groups heard giving their trilling flight call as they passed overhead. Skylark flocks often join other species which are also moving south, such as Meadow Pipits and even the occasional Woodlark.

Gadwall and Pintail typically arrive a bit later in the autumn, but are already joining the increasing numbers of Teal and Wigeon as birds arrive from Iceland, arctic Russia and Fennoscandia. Records of Pink-footed and Brent Geese are also climbing, and the first small arrival of Whooper Swans was noted last week with family groups arriving from Iceland.

Jay reports continued to increase as birds stockpiled acorns ahead of the coming winter. Their distinctive flight, white rump, and raucous call make them a conspicuous species throughout the year, but they are even more noticeable during the autumn months when their foraging activity increases.

Further afield, an astonishing migration of Coal Tit was seen in southern Finland, where over 36,600 were counted on Monday. We don’t often think of this species as migrating, but many of the members of the tit family are in fact partial migrants and will move south from Fennoscandia to avoid the colder temperatures of winter. Coal Tits from Continental Europe are reported each autumn in the UK; these birds are of the European subspecies Periparus ater ater (the British subspecies of Coal Tit is Periparus ater britannica) and can be distinguished from their British counterparts by a slight crest as well as bluish-grey on the back and wings.

Looking ahead

Over the coming weekend, a spell of south-westerlies will be followed by a band of rain across much of Ireland and the northern half of Britain. Most small migratory birds such as warblers will likely keep their heads down during such inclement weather, but waders and seabirds often carry on migrating and feeding regardless. Visiting coastal headlands in the south-west is likely to prove productive for seawatching; look out for Sooty, Great, Balearic, and Cory’s Shearwaters. With luck, the occasional Sabine’s Gull, Leach’s Petrel, or Grey Phalarope will also be in the mix. A visit to an estuary should provide a nice mix of waders, with Grey Plover, Turnstone, and Snipe all on the move at this time of year. Snipe are best looked for around the reedy edges of pools, and you may even score with a Jack Snipe. Look out for their bobbing feeding behaviour.

Yellow-browed Warblers have a reputation for turning up anywhere – getting familiar with their call will help you identify this lovely species.

Much of next week is forecast to be dominated by southerlies and westerlies of varying strengths. If the winds are light enough, birds will try to continue on their migration, especially if they have been held up in one area for a few days. Look out for flocks of Siskin, Redpoll, and Skylark on clear mornings; amongst these will be the occasional Pied and Grey Wagtail. Flocks of larks and pipits are always worth searching for rarer species, especially those which are feeding, as this affords the best views. A Lapland Bunting, Woodlark, or maybe even a Richard’s Pipit or Short-toed Lark are all possible additions to these flocks. With the good arrival of Yellow-browed Warblers a couple of weeks ago, we can also expect to see many of these birds filtering south, potentially turning up anywhere with trees or larger shrubs. Listen out for their distinctive “tchu-wee” call.

Late September into early October is the peak arrival time for Dark-bellied Brent Goose; this species’ core wintering range in Britain extends south and west from the Humber Estuary as far as Dorset. Around 135,000 birds (of both Light-bellied and Dark-bellied subspecies) winter in the UK and are most often found at coastal locations and estuaries. Flocks of Brent Geese are made up of family groups, with this year’s offspring accompanying their parents. The juvenile birds’ light wing bars and dark neck, which lacks the adult birds’ unmistakable white neck patch, make them easy to recognise.

Whooper Swans will continue to arrive from Iceland, although we will probably have to wait a few more weeks for reports of their close relatives, the Bewick’s Swan, which breeds in arctic Russia. Like Brent Geese, Whooper Swans often travel as a family group, with the young birds identifiable by their dark head and neck feathering and paler bills. These groups will stay together until the spring and can form large flocks or herds during the winter months.

If rarities are your thing, then you probably need to look to other American vagrants which may be swept across the Atlantic. Wilson’s Phalarope and Spotted Sandpiper are the most likely, given the time of year. Laughing or Bonaparte’s Gull must also be on the cards, but if we want to go even rarer, how about another Sora or Rose-breasted Grosbeak?

Send us your records with BirdTrack

Help us track migration amidst an outbreak of avian influenza.

Submitting your sightings to BirdTrack is quick and easy, and gives us vital information about our breeding and migrating birds.

Find out more

Share this page