Starling

Sturnus vulgaris (Linnaeus, 1758)

SG

STARL

STARL  15820

15820

Family: Passeriformes > Sturnidae

The Starling is perhaps best known for its squabbling behaviour at bird feeders, and the huge flocks which form dancing murmurations during the winter.

At close quarters, the dark-looking Starling is a colourful bird; its breeding plumage is iridescent green, blue and purple and it is spotted with silver in the winter. The Starling mainly feeds on soil invertebrates, although it commonly visits garden feeders. Starlings often nests in the eaves of our houses, where their song - full of the masterful mimicry of other birds and even machines - can be fully appreciated.

Starlings can be found across Britain & Ireland except for the highest peaks. Numbers increase dramatically during the winter months when birds arrive from northern Europe and larger roosts can number over a million birds. The species is on the UK Red List due to a sharp breeding population decline since the 1960s.

Exploring the trends for Starling

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Starling population is changing.

trends explorerIdentification

Starling identification is usually straightforward.

SONGS AND CALLS

Listen to example recordings of the main vocalisations of Starling, provided by xeno-canto contributors.

Begging call

Alarm call

Call

Song

Develop your bird ID skills with our training courses

Our interactive online courses are a great way to develop your bird identification skills, whether you're new to the hobby or a competent birder looking to hone your abilities.

Browse training coursesStatus and Trends

Population size and trends and patterns of distribution based on BTO surveys and atlases with data collected by BTO volunteers.

CONSERVATION STATUS

This species can be found on the following statutory and conservation listings and schedules.

POPULATION CHANGE

The abundance of breeding Starlings in the UK has fallen rapidly, particularly since the early 1980s and especially in woodland (Robinson et al. 2002, 2005a), and continues to be strongly downward. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that decrease over that period was widespread across England and eastern Scotland but that some increase occurred in Northern Ireland, western Scotland and Cumbria. More recent BBS data suggest that populations are also now decreasing in Scotland and Wales and are broadly stable in Northern Ireland. The species' UK conservation listing has been upgraded from amber to red as the decline has become more severe. Widespread declines in northern Europe during the 1990s outweighed increases in the south, and the European status of this species is no longer considered 'secure' (BirdLife International 2004). There has been a decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

| UK breeding population |

-53% decrease (1995–2020)

|

Exploring the trends for Starling

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Starling population is changing.

trends explorerDISTRIBUTION

Starlings breed and winter throughout Britain and Ireland, although some parts of central Wales are unoccupied in the breeding season. Winter abundance is highest in low-lying pastoral farmland in the northeast and midlands of Ireland and in the west and southwest of Britain. In the breeding season, abundance is greatest across Ireland and in low-lying areas in eastern Britain and the Northern Isles, with other concentrations associated with urban area.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

| No. occupied in breeding season | 2749 |

| % occupied in breeding season | 91 |

| No. occupied in winter | 2752 |

| % occupied in winter | 91 |

European Distribution Map

European Breeding Bird Atlas 2

Breeding Season Habitats

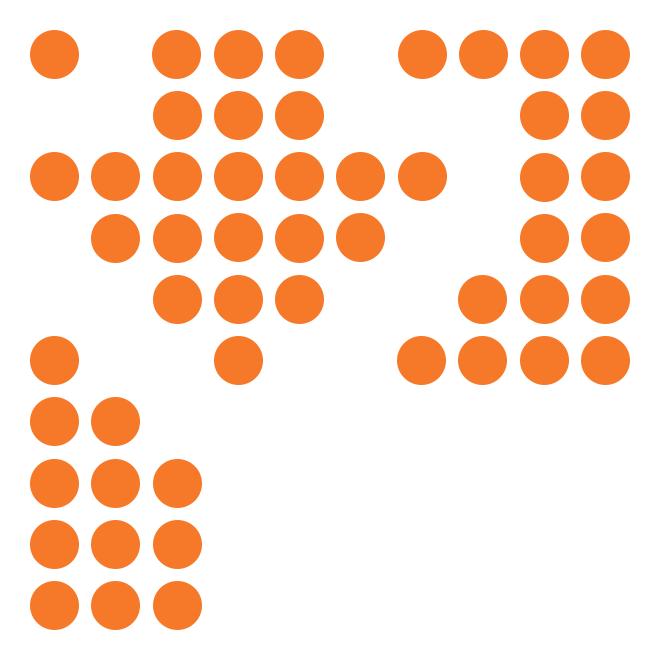

| Most frequent in |

Towns

|

| Also common in | Villages |

Relative frequency by habitat

Relative occurrence in different habitat types during the breeding season.

DISTRIBUTION CHANGE

The Starling's breeding range has changed little, but relative abundance within the core range has decreased, consistent with a 50% populaiton decline in the UK during 1995–2010.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

| % change in range in breeding season (1968–72 to 2008–11) | -5.2% |

| % change in range in winter (1981–84 to 2007–11) | +1.7% |

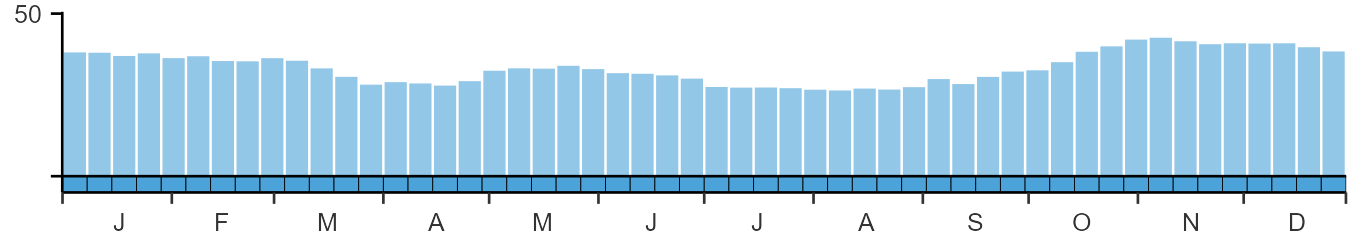

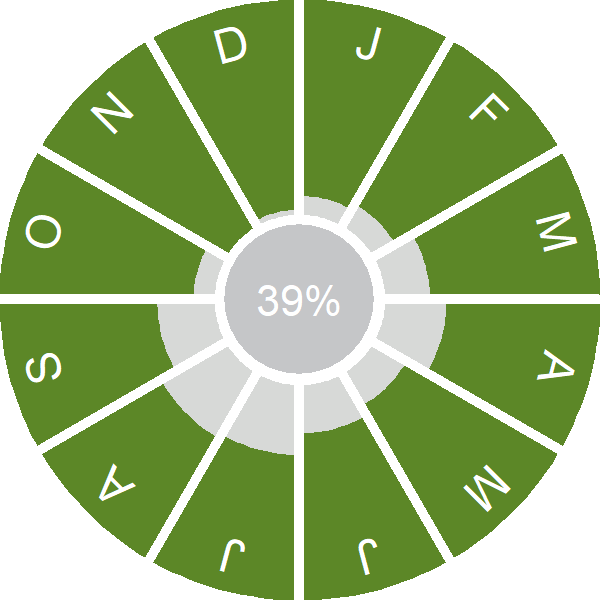

SEASONALITY

Starling is recorded throughout the year on up to 40% of complete lists.

Movement

Information about movement and migration based on online bird portals (e.g. BirdTrack), Ringing schemes and tracking studies.

An overview of year-round movements for the whole of Europe can be seen on the EuroBirdPortal viewer.

RINGING RECOVERIES

View a summary of recoveries in the Online Ringing Report.

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Biology

Lifecycle and body size information about Starling, including statistics on nesting, eggs and lifespan based on BTO ringing and nest recording data.

PRODUCTIVITY & NESTING

Exploring the trends for Starling

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Starling population is changing.

trends explorerSURVIVAL & LONGEVITY

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report

Maximum Age from Ringing

|

17 years 7 months 25 days (set in 2001)

|

Typical Lifespan

|

5 years with breeding typically at 2 year |

Adult Survival

|

0.687±0.004

|

Juvenile Survival

|

0.518 (in first year)

|

Exploring the trends for Starling

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Starling population is changing.

trends explorerBIOMETRICS

Wing Length

|

Adults | 131.3±3.5 | Range 126–137mm, N=32774 |

| Juveniles | 130.2±4.2 | Range 122-136mm, N=10312 | |

| Males | 132.6±3.1 | Range 128–137mm, N=18182 | |

| Females | 129.5±3.3 | Range 124–135mm, N=13930 |

Body Weight

|

Adults | 85.0±9.88 | Range 73.3–98.0g, N=24304 |

| Juveniles | 81.8±7.5898 | Range 70.0–95.0g, N=8104 | |

| Males | 87.0±9.97 | Range 76.0–100g, N=13448 | |

| Females | 82.5±9.27 | Range 72.0–95.0g, N=10351 |

Feather measurements and photos on featherbase

CODES & CLASSIFICATION

Ring size

|

C |

Field Codes

|

2-letter: SG | 5-letter code: STARL | Euring: 15820 |

For information in another language (where available) click on a linked name

Research

Interpretation and scientific publications about Starling from BTO scientists.

CAUSES AND SOLUTIONS

Causes of change

There is good evidence that changes in first-year overwinter survival rates best account for observed population change. Although the ecological drivers of Starling decline are poorly understood, changes in the management of pastoral farmland are thought to be largely responsible.

Further information on causes of change

As the population has dropped, the numbers of fledglings per breeding attempt has increased markedly (see above); clutches are now larger, and rates of nest loss at the egg and chick stage have fallen. These improvements in breeding performance suggest that decreasing survival rates are likely to be responsible for the decline. Evidence for this is provided by Freeman et al. (2007b), who conducted a population modelling exercise and found that changes in first-year overwinter survival rates could best account for observed population change, and were sufficient, on their own, to explain the broad pattern of decline. This pattern is supported by a more recent, integrated, population analysis (Robinson et al. 2014). The decline in survival rates nationwide coincided with the major period of population decline. MacLeod et al. (2008) also provide evidence linking Starling declines to the environmental conditions outside the breeding season, suggesting that the species' population status is dependent on interactive or synergistic effects of food availability and predation. Recent research in The Netherlands has identified changes in juvenile survival as the most likely explanation for similar substantial declines which have affected the Dutch Starling population since the 1990s (Versluijs et al. 2016).

There is little direct evidence from studies analysing the ecological drivers of the declines. However, changes in pastoral farming practices are likely to account for at least some of the decline in the wider countryside, probably related to changes in food resources, though these are largely unquantified (Robinson et al. 2005a). In Denmark, adults selectively forage in grazed areas when feeding nestlings (Heldbjerg et al. 2017), and the decline of the Starling has been linked to changes in grassland area and grazing density (Heldbjerg et al. 2016). A review by Heldbjerg et al. (2019) concluded that cattle abundance was most likely to explain the differences in trends across Europe, rather than grassland extent or temperature. Loss of permanent pasture, which is the species' preferred feeding habitat, and general intensification of livestock rearing are likely to be having adverse effects on rural populations in the UK, but other causes should be sought in urban areas (Robinson et al. 2002, 2005a). Whilst the number of cattle has declined, sheep numbers have increased, producing a different sward structure (Chamberlain et al. 2000b, Fuller & Gough 1999) and patterns of stock rearing have changed. These may have reduced foraging opportunities for Starling (Robinson et al. 2002, 2005a). Also the use of insecticides on grassland, though low, is targeted partly at tipulids, which may have reduced foraging opportunities further (Vickery et al. 2001). Although there is little published evidence that the density of tipulids has changed over time (Wilson et al. 1999), the area of permanent pasture, in which they are mainly found, has declined and the use of insecticides on them has increased. Drainage of grasslands is also thought to have reduced the quality of foraging conditions (Newton 2004). Even after considerable decline among farmland Starlings, tipulids remain important to them for provisioning young (Rhymer et al. 2012).

Suburban habitats important for Starlings with 60% of population in urban/garden habitats but relatively little known about them (Robinson et al. 2005a, 2006), and the causes of declines unclear though nesting attempts produce fewer young than rural birds (Siriwardena & Crick 2002 ). Town populations are doing best in the north and west but declining in the south (Robinson et al. 2005a). Further research into urban Starling population dynamics is to be encouraged if we are to understand the causes of decline of this charismatic species more fully.

Information about conservation actions

In rural areas, changes to pastoral farmland are most likely to be responsible for declines, with the intensification of livestock rearing and loss of permanent pasture reducing foraging opportunities (see Causes of Change section, above). Adults selectively forage in grazed areas when feeding nestlings (Heldebjerg et al. 2017), therefore maintaining grazing at this time is likely to be important. However, as the declines are believed to be driven by reduced first year survival, continued provision of suitable foraging habitat after fledging may be more important. Starlings capture more prey on short swards and providing short swards by grazing or mowing could therefore be a good way to improve foraging habitat (Devereux et al. 2004).

A reduction in the use of insecticides on grasslands may also benefit Starlings by improving foraging opportunities. Although the use of insecticides is low, it is targeted partly at tipulids which are an important prey item for Starlings (see Causes of Change section, above).

Starlings are also declining in urban areas which support around 60% of the population (Robinson et al. 2005a). Urban Starlings produce fewer young than rural birds (Siriwardena & Crick 2002) and urban birds are declining more strongly in the south of Britain than in the north and west (Robinson et al. 2005a). However, the reasons for the decline in urban areas are unclear and further research is needed before evidence-based conservation actions can be proposed.

PUBLICATIONS (1)

Drivers of the changing abundance of European birds at two spatial scales

Study highlights significant losses of European birds

This piece of research explores the question of measuring and detecting biodiversity change for European birds, which are well monitored in many European countries thanks to ongoing monitoring prog

Links to more information from ConservationEvidence.com

Would you like to search for another species?

Share this page