BirdTrack migration blog (winter 2023/24)

On the sea

In November, a succession of storms brought torrential rain, flooding and strong winds to much of the UK. Storm Ciarán swept across the south coast of England then pushed eastwards up the English Channel and into the North Sea, rewarding those willing to brave the gale-force winds with a host of late autumn seabirds.

Grey Phalaropes, Little Gulls, and the occasional Sabine’s Gull were noted, but it was Leach’s Petrel that was on most people’s radar – and this species didn’t disappoint. Several sites along the south-eastern coast of Britain logged good numbers, with a count of 115 in East Sussex being topped by a huge tally of 203 further along the coast at Dungeness, Kent. This same site also recorded an amazing 84 Storm Petrels, making for a truly memorable day of seawatching.

The sea provided yet more birdwatching during November as divers continued to head south to their traditional wintering areas, often in sheltered bays. BirdTrack saw an increase in reports for both Black-throated and Great Northern Divers, with some individuals being found on some inland reservoirs and lakes in addition to the stream of birds seen offshore.

Waxwings

Waxwings have continued to grace berry bushes up and down the country, much to the delight of birders and non-birders alike.

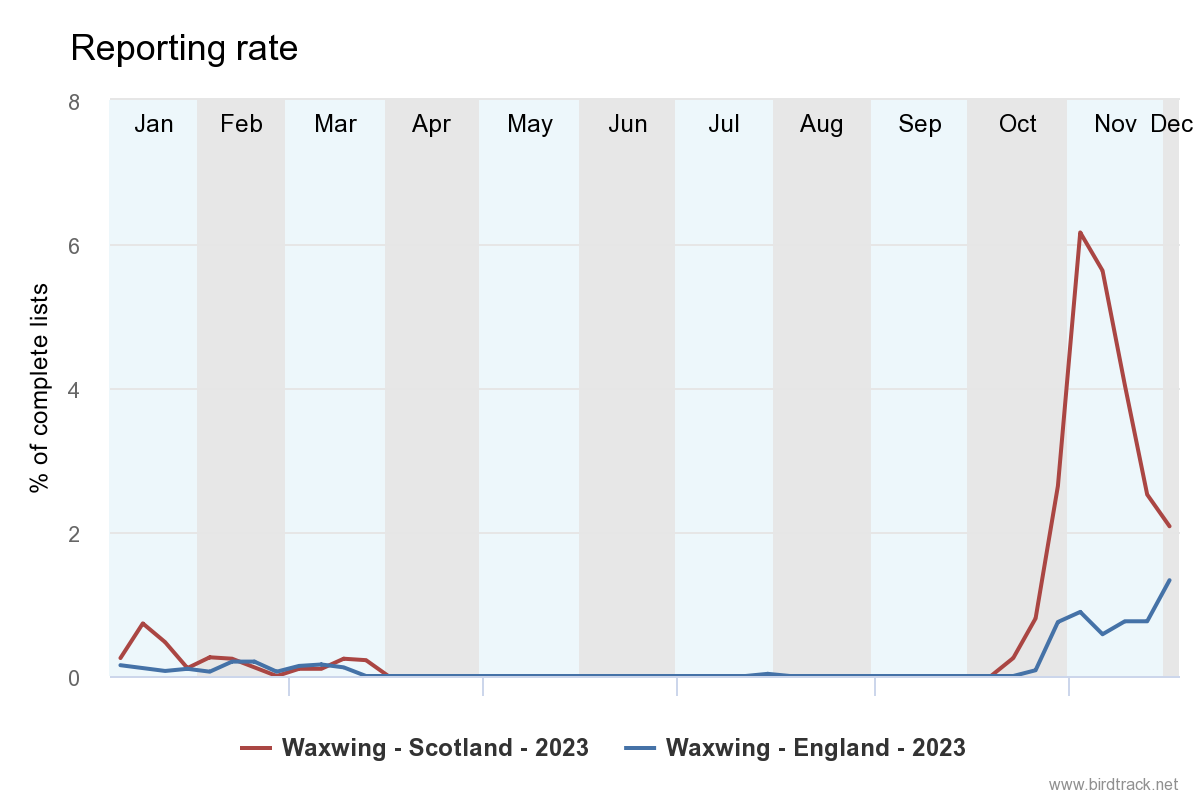

In early November, the bulk of the sightings came from Scotland as birds arrived from across the North Sea, but over the last few weeks, flocks have pushed further south and west in search of new berries on which to gorge themselves. The BirdTrack reporting rates for Scotland and England show this shift in occurrence nicely, with reports falling away in Scotland while increasing across England.

The Grampian Ringing Group has been running a Waxwing colour-ringing study for a number of years to help researchers understand how flocks move across the country, if they winter in the same locations each year, and whether the birds’ wintering locations correlate with particular breeding populations in Fennoscandia. Each bird is given a unique combination of coloured rings, so individuals can be identified in the field.

You can help the group with their studies by reporting any colour-ringed Waxwings that you see – in doing so, you will also find out when and where the bird you saw was ringed! You will need to make a note of the colour of any rings, as well as their position and which leg of the bird they are on – if you have a camera, photographs can be a useful reference for this.

Looking at Waxwing reports across the rest of Europe, there appears to be a similar influx occurring in eastern Poland as flocks filter south through Sweden, Denmark, and Germany. You can watch this movement on EuroBirdPortal. Here in the UK, we will need another spell of easterly winds before we see any further significant arrivals on this side of the North Sea.

Wildfowl, waders and gulls

Wildfowl continued to arrive from across Europe, with numbers of White-fronted Geese, Pintails, Pochards and Goldeneyes building. Goosanders, Red-breasted Mergansers and the first few Smews also gave a real wintery feel to the end of November as they moved to established wintering areas. These three species are diving ducks, with fish being their main prey item – their serrated bills, supremely adapted to catching fish underwater, give rise to their colloquial epithet ‘sawbill’. While Goosanders and Smews have a preference for freshwater habitats, Red-breasted Mergansers can often be found either on the sea around shallow coasts or on estuaries.

Bewick’s Swan is typically one of the last winter visitors to arrive in Britain and Ireland, and the species has been arriving later and later in recent years. This winter has been no different; the first arrival occurred in mid November, some 10–14 days later than the historical average. Studies have shown that this is in part due to birds ‘short-stopping’ on their migration, travelling less far south and west as climate change increases winter temperatures across northern Europe. You can read more about this phenomenon in the Waterbirds in the UK article ‘Short-stopping unwrapped’.

Short-stopping is partly responsible for the huge decline in the UK’s wintering population of Bewick’s Swan, which fell by 95% between the winters of 1995/96 and 2020/21. The Ouse and Nene Washes hold the largest flocks, but keep an eye out anywhere in south-eastern England for small groups or herds which can turn up, sometimes in the company of their larger Whooper Swan cousins.

Purple Sandpipers are seen as true winter visitors by many birders, with around 9,000 of these lovely waders spending the colder months across Britain and Ireland. This species is a very rare breeder in the far north of Scotland, so the bulk of the wintering birds are those which arrive from Greenland and Norway.

They are birds of rocky coasts and can be found feeding amongst the crashing waves as they pick up invertebrates washed in from the sea. In bright light, the purplish sheen that gives them their name can be seen on their mantle (back) feathers. More and more birds have been reported since mid November, with some sites playing host to small flocks.

Reports of Mediterranean, Great Black-backed, and Caspian Gulls were also on the rise in November, and these birds have now been joined by the first Iceland and Glaucous Gulls of the year. Both of these latter species breed north of the UK; they look similar to Herring Gulls but lack the black wing-tips, instead having white primaries that earn them the nickname ‘white-wingers’. Numbers are, however, lower than expected for this time of year, perhaps due to a lack of northerly winds which usually carry these birds to the UK in recent weeks.

Help us monitor wintering gulls

You might already be sending us your gull records through BirdTrack, but did you know we are also looking for volunteers for the Winter Gull Survey?

If you are confident identifying the six main species of gull found in the UK in winter – Herring, Lesser Black-backed, Great Black-backed, Black-headed, Common and Mediterranean – visit the WinGS project pages to find out more about taking part.

Volunteers will only need to make a small number of visits to gull roosts between 2023 and 2025, but their contributions will help us fill in vital gaps in our understanding of these Amber- and Red-listed species.

How to take part in WinGSFinches, larks and buntings

A scattering of Snow Bunting and Shore Lark reports have been a delight; both species are firm favourites with birders during the winter. Snow Buntings in particular can form large flocks, and their striking black and white wing pattern is very distinctive when they are seen in flight.

Twites are closely related to Linnets, and as their old English name Mountain Linnet suggests, they have a preference for upland habitats. However, after the breeding season, British Twites move away from higher altitudes and spend the winter around our coasts. The declining population means records are becoming scarcer – traditional wintering areas such as Thornham in North Norfolk have seen numbers dwindle each year, and the species is now a rare winter visitor in Norfolk where double-figure counts were once regular.

So far this winter, reports have again been low, with the highest counts coming from a couple of locations in Northumberland and Lancashire. Two birds spotted in Kent have been popular with birders due to the paucity of this species there in recent years. It is worth checking any finch flocks you may encounter at the coast; the Twites’ pale yellowish bill and pink patch above the tail help differentiate them from the similar-looking Linnet.

Rarities and scarcities

Since the last blog, the rarity highlights have had an American bias: a Cape May Warbler in the Isles of Scilly, the first White-crowned Sparrow for Cornwall, an American Robin and a Rose-breasted Grosbeak in County Cork and a Baltimore Oriole in Fife all originated from the other side of the Atlantic.

A Brünnich’s Guillemot in the Scottish Borders and a Little Crake in Buckinghamshire provided further interest, while a Canvasback in Essex sparked some lively discussion as to its origins – a transatlantic vagrant or simply a fence hopper from a wildfowl collection?

This handsome duck is a North American species, closely related to the Pochard, Tufted Duck, and Greater and Lesser Scaup. It is a rare visitor to the UK and findings are often contested because it is a popular species in ornamental duck ponds, making records tricky to verify.

“A Canvasback in Essex sparked some lively discussion as to its origins – a transatlantic vagrant or simply a fence hopper from a wildfowl collection?”

Looking ahead

As we edge ever closer to the shortest day of the year, large-scale migration slows week by week with the main drivers of bird movements being freezing weather and snow.

The Gulf Stream keeps temperatures a few degrees warmer across much of Britain and Ireland compared to the rest of Europe, and it is during times of prolonged freezing temperatures and snow that several species head to our shores to escape the harsh weather. These cold weather movements are very dependent on the extent of the freezing conditions and their duration; the longer these cold snaps last and the larger the area they affect, the greater the likelihood that birds will arrive here.

Species displaced by such extreme cold periods are typically those that live on or near water or need soft ground in which to feed. Waterfowl are often forced to migrate in search of open water in icy conditions, with a variety of ducks, geese, and swans arriving en masse. These might be joined by ground-feeding species such as Snipe, Woodcock, and thrushes in search of unfrozen earth to probe for worms and other invertebrates.

“Species displaced by extreme cold periods are typically those that live on or near water, or need soft ground in which to feed – look out for ducks, geese and swans as well as Snipe, Woodcock and thrushes.”

Cold winds are also likely to bring more Iceland and Glaucous Gulls to our shores. These are regular winter visitors to Britain and Ireland, but the numbers arriving each winter are very dependent on the weather with the bulk of birds arriving during northerly winds.

This year, there have only been a couple of days when this type of weather pattern has occurred, and as a result, only a scattering of birds have been reported, mainly in the Outer Hebrides, Western Scotland, and Northern Ireland. As the winter progresses, more are likely to arrive, especially after any winter storms that have tracked across Iceland. Most of the birds that turn up here will be in their first winter, and their pale milky-tea plumage helps pick them out from similarly aged Herring and Lesser Black-backed Gulls.

Even if there isn’t any particularly cold weather across Europe, winter is always a good time of year to look for Bullfinches. These are secretive birds and can be difficult to see during the summer months, which is surprising given their large size and bright plumage. Any areas of dense scrub with some larger bushes are worth checking; Bullfinches will often feed on the berries of hawthorns. Their soft “heeew” call is worth learning as they are more often heard than seen.

“Bullfinches can be extremely secretive but listening out for their soft call is a good way of finding them.”

Now is also a good time of year to look for some of the scarcer grebe species. Varying numbers of Black-necked, Slavonian, and Red-necked Grebes winter across the country and can be found on a variety of waterbodies, from lakes and inland lochs to estuaries and even on the sea.

Black-necked and Slavonian are the smallest of the three – a bit bigger than Little Grebes, with white and dark grey plumage that helps separate them from this browner-plumaged cousin. Learn how to distinguish Black-necked and Slavonian Grebes in our winter grebe ID video.

Red-necked Grebes are slightly smaller than Great Crested Grebes but share a similar body profile of a long neck and sleek body, but the neck tends to be dirtier looking than the pristine white seen on Great Crested Grebes.

Any trees or shrubs with berries are worth checking regularly: Blackbird, Redwing, Fieldfare, Waxwing and even the occasional overwintering Blackcap can be found feasting in them.

You can attract many of these birds to your garden by putting apples out, with the added bonus of being able to watch the birds from the comfort of your own home! Who knows, you may even attract a rarity – Black-throated Thrush and Dusky Thrush have both been found in people’s gardens in recent winters.

Other rarities that have occurred at this time of year include Blyth’s Pipit, Baikal Teal, and Ivory Gull, all of which are sure to brighten up the dullest of winter days.

Tracking avian influenza: send us your records with BirdTrack

So far this winter, cases of avian influenza seem to be falling – but we still urgently need your help to monitor the spread of the disease.

It’s quick and easy to submit cases to Defra or DAERA and BirdTrack, and gives us vital information about cases in real time.

Learn how to report cases of avian influenza

Share this page