With this year's focus on heathland birds here at BTO, monitoring of Nightjars is very topical. Being nocturnal, detecting them requires dedicated night-time field surveys, which can be tricky in remote areas. Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM) can be a useful tool to help in Nightjar monitoring, as programmable audio recorders can be deployed in the daytime and left to record for extended periods. Software like the BTO Acoustic Pipeline that can then be used to efficiently scan the many hours of collected audio, automatically searching for Nightjar vocalisations. This type of digital surveying can be especially useful in areas of low Nightjar density or on the edge of the species' range, where unpaired birds may wander widely and be difficult to detect by human surveyors. But what if we want to understand more than simply whether there was a Nightjar present? Can we say whether Nightjars are paired or even nesting just based on passively collected sounds?

Nightjars are probably most well known for the continuous churring song produced by males. This vocalisation has a slow and a fast version which males use interchangeably. Nightjars (adult males and females, and juveniles) also produce a nasal “groeek” call, which is most often given in flight. The following recordings provide examples of both (in both spectrogram and playable sound file form – you can find tips for interpreting spectrograms here). Existing software solutions are already able to detect these sounds but they don't differentiate among them, merely indicating that Nightjar sounds have been found.

Spectrogram of Nightjar churring.

Spectrogram of Nightjar “groeek” calls with juvenile Long-eared Owls in the background.

Nightjars also ‘wing-clap’ – a sharp cracking sound produced when the male slaps his wings together over his back – usually in response to the presence of a female or a rival male. This type of cue would be great to detect automatically in passive recordings, as it would provide a strong indication of an established territory. In atlasing terminology, this could elevate the detection from merely ‘possible breeding’ to ‘probable breeding’.

Unfortunately, wing claps are very simple sounds and in our early trials the computer algorithms we developed to search for wing claps tended to make lots of mistakes on everyday sounds like snapping twigs and even some other bird sounds, making it impractical to use wing claps as a diagnostic feature in passive recordings. Fortunately, Nightjars produce two other sounds that are more distinctive and provide behavioural insights.

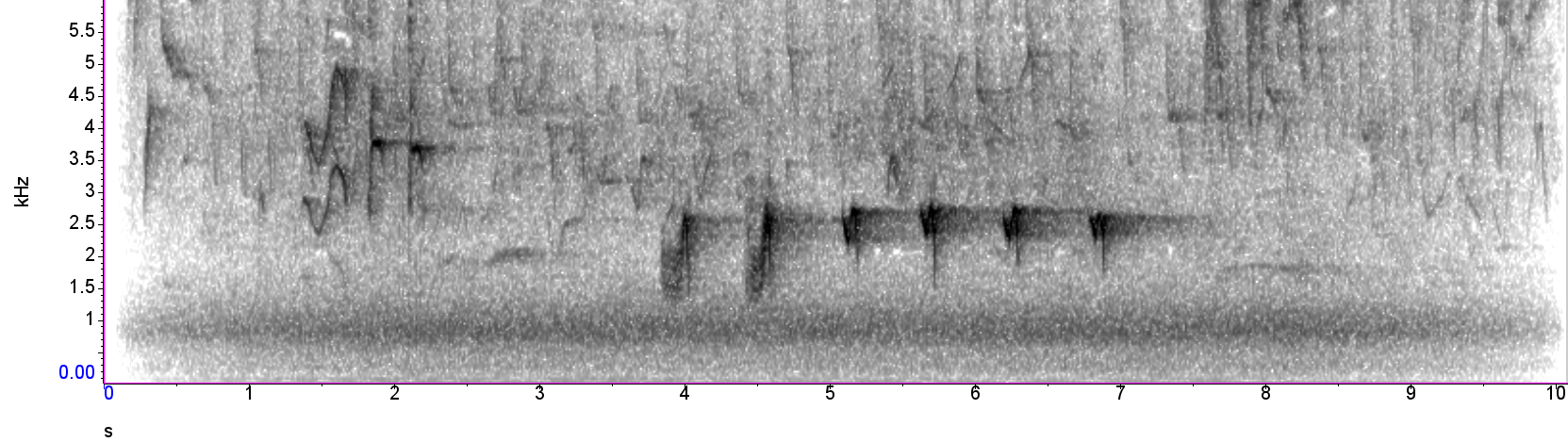

Spectrogram of churring transitioning into purring (at 3.5 seconds) with six wing-claps (tall vertical lines).

The first of these, which I call ‘purring’, occurs when a male transitions from his normal churring to a slower pulsed (or purring) sound. This distinctive sound is only produced in courtship when a female is present, often when prospecting for a nest site, potentially indicating the presence of an established pair. Unlike the wing claps, purring is acoustically more complex, providing more ‘pattern’ for a classifier to search for and separate from ambient sounds.

Finally, Nightjars also produce a series of hard knocking “toc” calls. These are usually produced when the bird is agitated and can be a sign there is a nest nearby. The intensity of this calling increases from late incubation to chick fledging, so intense repetitive calling is a good indicator of a nest containing young. When a human observer is present, it may be our own presence that triggers this response. In the case of a passive audio recorder there is no observer present, so we may not record this call so often, unless other disturbance events occur, such as other people, domestic animals or predators. Nevertheless, if we do detect this sound in passive recordings, it would be a strong indicator of nesting activity.

Spectrogram of “toc-toc” agitation calls (short, vertical lines, strongest between seven and 10 seconds). Cuckoo and Skylark are also audible.

To allow us to automatically detect these different sounds, and to give us a chance of extracting behavioural signals from audio recordings, we've trained a new machine-learning classifier. Machine learning is the use of computer algorithms and statistical models enabling computers to learn patterns, and to look for those patterns in new data. In this case, we train models (or classifiers) to recognise bird sounds based on meticulously labelled examples of these different song and call types sourced from BTO recordings and those contributed to the excellent xeno-canto sound library. Once the classifier is trained, it can be used to search for these sounds in new unseen recordings.

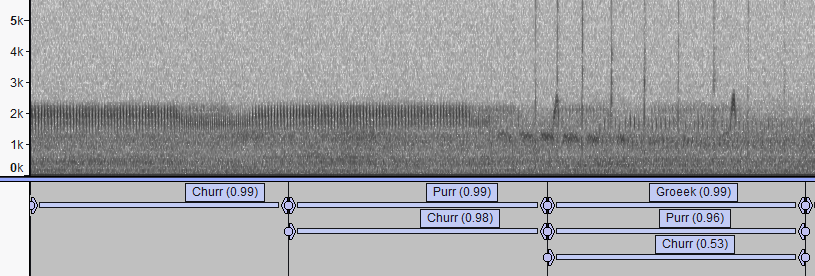

Spectrogram image with labels for churring, purring and “groeek” calls, generated automatically by applying the Nightjar call-types classifier in the BTO Acoustic Pipeline. Recorded 17 June 2025 in Thetford Forest by Simon Gillings.

The figure above shows a typical output from applying the new classifier to novel recordings, with each three-second chunk of audio assigned a score for the likelihood of it containing one or more of the four Nightjar call types. In independent trials, the classifier was able to detect virtually all churrs and purrs and a high proportion of “groeek” and “toc-toc” calls.

Passive acoustic monitoring offers lots of potential for complementing traditional survey techniques. However, the machine learning tools that make it possible are not infallible. For example, the spectrogram and recording below show an automated detection of a Nightjar “groeek” call. In isolation this looks like a 100% certain Nightjar detection, until you realise this was recorded at 7 a.m., which is a very unlikely time of day for a true Nightjar detection. A more thorough inspection shows this is actually a Song Thrush weaving very accurate Nightjar mimicry into its song! This cautionary tale highlights the need for manual checking (a so-called ‘human-in-the-loop’) in any project using acoustics and automated identification tools.

Spectrogram image of a Song Thrush weaving mimicry of Nightjar “groeek” calls into its song.

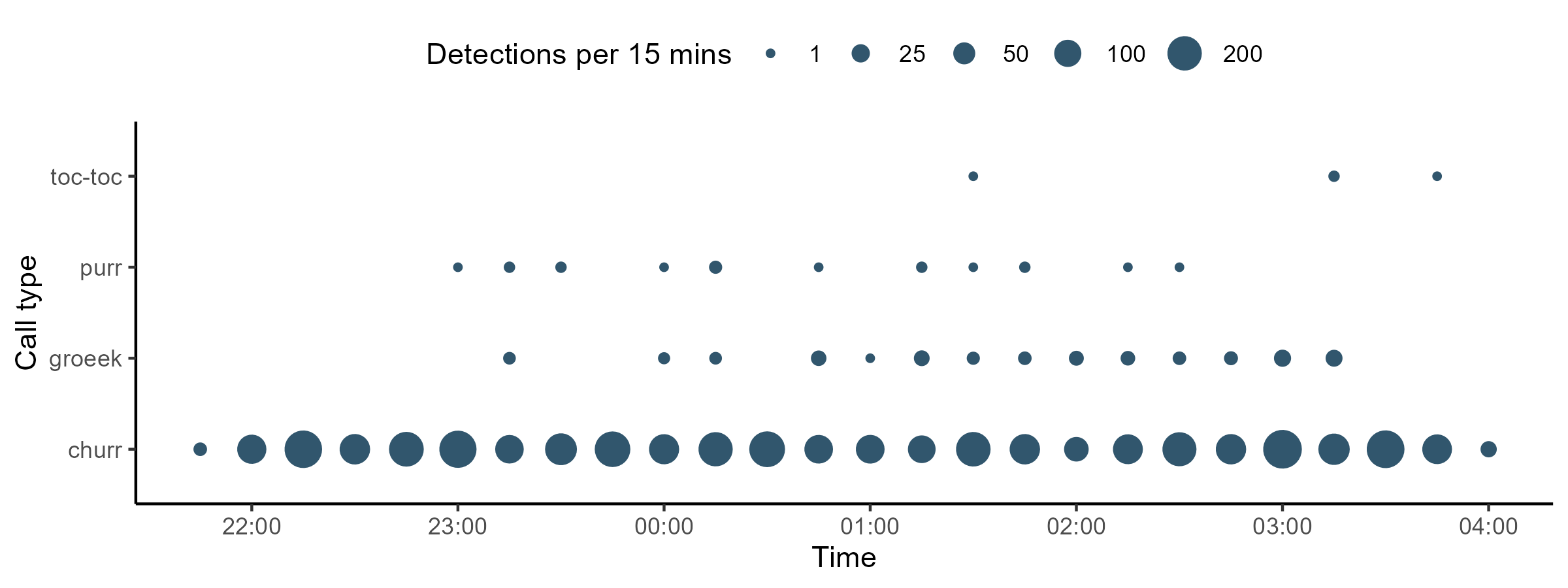

One attraction of passive acoustic monitoring is the ability to record unattended for long periods and to see patterns of behaviour through time. The figure below shows the number of detections of the four calls types from one night of recording in Thetford Forest. You can see that churring occurred all night, which is a likely indication there are unpaired males present, as paired males typically stop churring soon after dusk. Purr calls scattered through the night suggest one or more females were present, and calls late in the night suggest a nest nearby.

The number of detections of four Nightjar call types during one night of continuous recording in Thetford Forest.

The Nightjar call-type classifier is one of several bespoke classifiers we provide via the Acoustic Pipeline. Others include call types of Curlews, Lesser Spotted Woodpeckers, and nocturnal flight calls. We have classifiers in development for all UK bird species plus other audible taxa such as deer and amphibians. For the processing of audible recordings the Pipeline is free to use, subject to fair usage policies. The Pipeline can also be used for the processing of ultrasonic bat recordings for which credits and costs may apply. We are always keen to hear how we can help support conservation and management-focused acoustic monitoring.

Thanks to BTO’s resident Nightjar experts Greg Conway and Ian Henderson for their insights into Nightjar behaviour. Thanks also to Carlos Abrahams and the wider sound recording community for sharing sound recordings used in classifier training and evaluation.