Learn about passive acoustic monitoring: what it is, how it works, and why it’s a powerful tool for ornithological research and conservation. You can also visit our acoustic monitoring research page for information about BTO’s work in this area, and about BTO's Acoustic Pipeline.

What is passive acoustic monitoring?

Passive acoustic monitoring* involves using recording equipment to capture sounds from the environment, and analysing the recordings to develop our understanding of the environment and the species that live within it. It is called ‘passive’ because recording equipment is left unattended to capture naturally occurring sounds in the environment. In contrast, ‘active’ acoustic monitoring typically involves researchers transmitting sound into the environment and monitoring the echoes to determine the location or movement of objects or animals.

It can be used to survey any wildlife which makes sound, in a variety of different habitat types, for example, woodlands, wetlands and heathlands. At BTO, we use it to study species such as birds and small mammals, which make sounds that are audible to human ears. We also use it to study species like bats and invertebrates which make ultrasonic sounds that humans cannot hear.

*Passive acoustic monitoring (abbreviated to PAM) is also often referred to as acoustic monitoring, bioacoustics or ecoacoustics.

How does passive acoustic monitoring work?

Passive acoustic monitoring is made up of two key processes: recording sounds from the environment and analysing and interpreting the recordings.

Recording sounds from the environment

Passive acoustic monitoring uses a range of audio devices to capture sound. Although the sound can be monitored in real-time, in ornithology, and in our research, acoustic monitoring typically involves deploying recording equipment for a set time period and analysing the recordings at a later date.

Passive acoustic monitoring uses a range of audio devices to capture sound. Although the sound can be monitored in real-time, in ornithology, and in our research, acoustic monitoring typically involves deploying recording equipment for a set time period and analysing the recordings at a later date.

- Acoustic recorders can be set to run continuously, to run on a particular schedule (e.g. 3 hours around dawn), or to start recording when they are triggered by a sound.

- Recording devices are often tailored to capture and record the frequencies of a particular species group.

- Many acoustic monitoring recorders are able to capture low-frequency and ultrasonic sounds, which are outside the range of human hearing. This gives us a more complete picture of the environment.

Examples of recorded sounds

Sounds that we might record as part of BTO acoustic monitoring research include:

- Bird sounds, such as songs to attract a mate or establish territory, or calls to communicate with young.

- The ultrasonic calls used by bats for echolocation, to navigate and find food.

- Moth ‘squeaks’, produced to confuse predators like bats, or to mimic a queen Honey Bee and gain access to a hive for honey.

- Cricket ‘song’, produced by males rubbing their wings or legs together, to attract females.

- Vocalisations made by small mammals like the Common Dormouse.

- Recorders can also capture other sounds from the environment, and have been used in conservation projects beyond the UK to detect chainsaws indicative of illegal logging, and gunshots indicative of poaching.

Analysing and interpreting acoustic recordings

Once recordings have been collected, the next step is to find and identify the sounds captured in the sound files.

Spectrograms

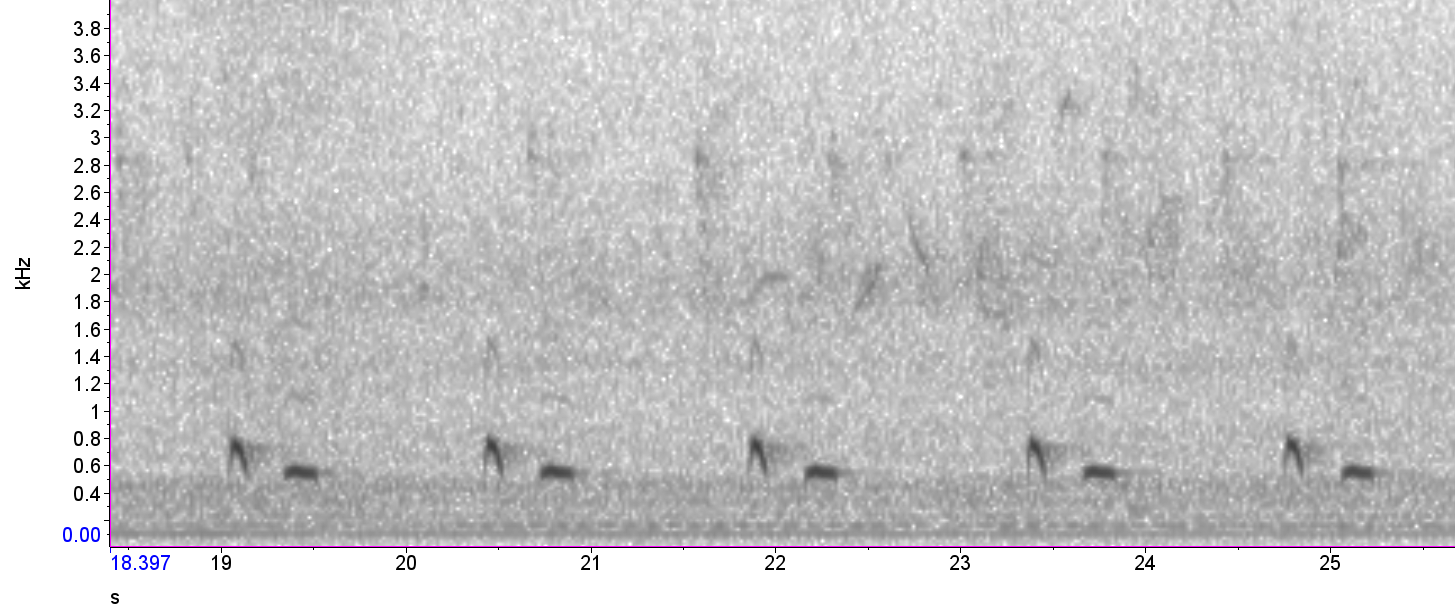

One method for finding and identifying sounds in the sound files is to represent the file as a spectrogram. A spectrogram is simply a visual representation of sound, which shows us how the sound’s frequency (commonly referred to as pitch) changes over time. Amplitude (loudness) is shown using a kind of ‘heat map’, where quieter sounds and louder sounds appear in different colours or intensities. Spectrograms are frequently used in BTO research, and are also available to amateurs and volunteers through sound editing and recording programmes like Audacity.

This spectrogram displays the song of a Cuckoo. The vertical axis (on the left) represents frequency, and the horizontal axis (along the bottom) represents time. The amplitude (volume) is represented by a grey-scale heatmap: the louder the sound, the darker it appears on the spectrogram.

Listen to the audio clip of the same Cuckoo song:

Spectrograms can be thought of as the visual ‘fingerprints’ of a sound. Each bird call has its own fingerprint: a unique shape and location on the spectrogram. The fingerprints allow us to identify the sound and the species that made it simply by looking at how it appears on the spectrogram.

Using a spectrogram allows us to visually scan recordings to find sounds of interest, which is much quicker than listening. It is particularly useful for recordings of sounds that are not audible to human ears, like the ultrasonic calls of bats.

- Learn more about reading and interpreting a spectrogram.

Acoustic classifiers

Scanning spectrograms is quicker than listening to the original audio files. However, manual detection and identification of sounds using spectrograms is often not feasible when sifting through many hours or even days of recordings. It can also be subject to human error: as has been shown in clinical screening of x-rays, humans can make mistakes when doing repetitive tasks when tired.

In recent years, acoustic monitoring has increasingly involved ‘classifiers’ – machine learning algorithms which are able to detect the unique signatures of wildlife sounds and identify them, processing hours of recordings in mere minutes. Classifiers are ‘trained’ on expert-verified recordings of wildlife sounds, and are increasing in accuracy as technology evolves. Despite big advances in classifiers and artificial intelligence, these systems still make mistakes and verification by skilled experts is still required to ensure unexpected or rare sounds are correct.

Scientists at BTO have developed classifiers for ultrasonic wildlife sounds, including those made by bats, small mammals and bush-crickets, and classifiers for audible wildlife sounds, including those made by birds and small mammals. These classifiers are available for anyone to use through the BTO Acoustic Pipeline.

Why do ornithologists use passive acoustic monitoring?

Passive acoustic monitoring can be used alongside traditional field survey methods (where researchers, fieldworkers or ecologists conduct surveys of wildlife in person) to collect information about bird populations and their movements.

Passive acoustic monitoring and field surveys have complementary strengths and weaknesses, so using them together usually results in more accurate and comprehensive information than either one alone.

Surveying less vocal and shy birds

Some species do not make many sounds, and are tricky to spot during surveys too. For example, Lesser Spotted Woodpeckers call very infrequently, especially if they are present at a low density in an area - when there are few other woodpeckers nearby, they do not need to call to defend their territory. They are also reclusive. This can make detecting the birds difficult because there is a very low chance of the bird calling or being visible while a surveyor is present.

Other bird species are extremely shy, and display strong avoidance of humans. In these cases, the very presence of a fieldworker at a site can disturb them and affect whether the species is detected at that time. This makes calculating accurate population sizes difficult. For example, Capercaillies will avoid areas that have recently been visited by humans. To protect these species and help them recover, conservationists need as much information about them as possible.

A key benefit of passive acoustic monitoring is that recorders can be left recording for days or even weeks, giving them more opportunity to capture rare vocalisation events and to collect data without influencing the presence of shy species. Passive acoustic monitoring for species such as Capercaillie and Lesser Spotted Woodpecker provides us with more accurate information about their presence or absence in an area than can be gathered through traditional surveys.

Detecting nocturnal birds

Passive acoustic monitoring can capture the songs and calls of birds that are active at dusk and dawn, or even throughout the night, which can be impractical for traditional fieldwork. Some of our most threatened bird species are best surveyed at this time: Nightjars and Nightingales, for example. Using recorders to detect these birds can be more practical and detect more calls than traditional methods.

‘Nocmig’ (short for nocturnal migration) is a type of acoustic monitoring which records the nocturnal flight calls of migrating birds. Data from nocmig recordings can help reveal which species are using migratory flyways at what times, and detect changes in migration patterns that occur as a response to light pollution, urban development and climate change.

- Nocmig is a popular and accessible citizen science activity that you can do from your home. Find out how to get started with nocmig.

This recording is of the nocturnal flight call of migrating Redwing.

Surveying remote and difficult terrain

Recorders can be deployed in remote and difficult-to-access locations, such as on islands, in vast areas of forest or wetlands, or in mountainous terrain. For example, BTO research has used passive acoustic monitoring on Rathlin Island (off the coast of Northern Ireland), in the wetland wilderness of Polesia (an area bordering Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia covering more than 18 million hectares), and in the Scottish uplands. Some important wildlife sites may also have restricted access for other reasons, such as those on military sites. Acoustic monitoring allows researchers to gather continuous sound data more easily from areas like these that are resource-intensive for fieldworkers to visit.

For example, researchers have also used acoustic monitoring on Mousa, an island in Shetland that has been designated a Special Protection Area due to its large colony of breeding Storm Petrels.

These tiny seabirds spend most of their time at sea and return to their burrows at night, which makes them difficult to survey using traditional methods. They are Amber-listed in Birds of Conservation Concern 5, making them an important species to study and protect. The research demonstrated that acoustic monitoring could facilitate more regular and comprehensive monitoring at remote colonies of burrow-nesting seabirds.

This recording is of a Storm Petrel song.

Reducing disturbance to birds and the environment

Passive recording usually involves very little disturbance to wildlife, because only two trips are necessary: one to set up the recorder, and one to retrieve it. This means that recorders can be set up in areas that are highly sensitive to human disturbance – for example, nesting seabird colonies like those on Rathlin Island – to collect information about wildlife that is not possible to survey using traditional methods (where researchers, fieldworkers or ecologists conduct surveys of wildlife in person).

Passive recording usually involves very little disturbance to wildlife, because only two trips are necessary: one to set up the recorder, and one to retrieve it. This means that recorders can be set up in areas that are highly sensitive to human disturbance – for example, nesting seabird colonies like those on Rathlin Island – to collect information about wildlife that is not possible to survey using traditional methods (where researchers, fieldworkers or ecologists conduct surveys of wildlife in person).

On Rathlin Island, ornithologists are investigating whether bioacoustic monitoring could be used to study the presence of non-native Brown Rats, which predate seabird eggs and chicks. Data gathered by recording devices could help identify the best ways to control non-native rat populations and support devastated seabird colonies in recovery.

Reducing the need for ‘playback’ techniques

Playback is a method of monitoring which uses sound recordings to mimic an ‘intruder’ in an animal’s territory and thereby elicit territorial calling from the real birds in the area. This allows researchers to detect their presence.

Responding to an intruder can be stressful, though, especially during the breeding season when birds are more territorial. Continuous recording, like that in passive acoustic monitoring, captures sounds made by birds without surveyors needing to use ‘playback’ techniques. This means birds do not use time and energy – vital resources for caring for their young and defending their territories – responding to a non-existent threat.

Passive acoustic monitoring allowed researchers to confirm the presence of Eurasian Eagle-Owls in the Greater Côa Valley in Portugal without the use of playback techniques. These impressive birds had not been recorded in the area for many years and were thought to be locally extinct. Their calls were detected in continuous sound recordings collected by passive acoustic monitoring devices deployed in the valley.

Because of the eerie nature of the sound, the call is also known as ‘devil's cackles’!

Can passive acoustic monitoring help protect birds?

Passive acoustic monitoring helps us to better understand birds and other wildlife, and the environment – from studying interactions between individual animals to assessing population sizes and tracking migration. The more high-quality data we have about the environment, the better informed conservation policy recommendations will be.

The potential of acoustic monitoring for research and conservation still needs to be unlocked.

Support our work developing this important monitoring tool.

How can I get involved in acoustic monitoring?

Citizen science

You don’t have to be a scientist or a researcher to take part in acoustic monitoring.

One of the most popular types of acoustic monitoring for citizen scientists is ‘nocmig’ (short for ‘nocturnal migration’). It captures the nocturnal flight calls made by migrating birds (and other birds that call at night). It can be fascinating to review nocmig recordings and discover what has been flying over your house at night.

To get started with nocmig, you will need a method of recording sounds, and a way of viewing the sounds on a spectrogram.

A good option for recording sound is to use a laptop or PC connected to an external microphone like those used for recording talks and conferences. This is a relatively cheap option if you already have a laptop and with the correct set-up is perfectly adequate for basic nocmig.

For finding and identifying calls in your sound recordings, you can use audio software on a computer. The most popular software for nocmig is Audacity, or Raven. There are plenty of guides available to help you install and use these options.

- Learn more about nocmig equipment

When you have identified the calls in your recordings, you can submit your findings to BirdTrack (if you record in the UK), and a bird migration site called Trektellen. This allows scientists to use the records in research.

Ecologists and consultants

BTO’s Acoustic Pipeline provides tools for detecting and identifying birds, bats and other wildlife in audible and ultrasonic sound recordings. The Pipeline is free to use for bird identification for personal and conservation uses, and there are scalable pricing plans for ultrasonic and commercial projects.

Help us unlock the potential of acoustic monitoring for birds

To support our work developing acoustic monitoring tools, donate to our Acoustic Appeal today.