BirdTrack migration blog (27 October–2 November)

Leach’s Petrel, a small thrush-sized seabird that spends almost its entire life out over the open ocean, was particularly well-reported. Several locations recorded multiple birds, with Fife and Lothian seeing the bulk of the higher counts; reports from around Edinburgh were particularly notable, with 70 birds seen past South Queensferry and 34 off Musselburgh.

Good numbers of Little Gulls were seen along the east coast, often in small mixed-age flocks, with their dark underwing helping their identification. The highest counts for this species in the last week included 1,600 reported past Sheringham, Norfolk on 21 October.

The Shag is a close relative of the more familiar Cormorant but is found almost exclusively along rocky coastlines, with far fewer inland, riverine records. During the last week, several places along the east coast have seen large numbers of Shags moving south and unusually some of these have turned up inland, in very odd places – inside buildings, swimming down rivers, and even sitting on farm machinery at the edge of fields. Storms such as Babet can displace migrating birds quite significantly; those exhausted by the weather often hunker down in unusual spots to recover before moving on.

Storms such as Babet can displace migrating birds quite significantly; those exhausted by the weather often hunker down in unusual spots to recover before moving on.

A surge in Grey Phalarope reports also followed Storm Babet as migrating birds were pushed from the open ocean towards the coast. A count of 12 of these lovely birds at Newbiggin-by-the-Sea, Northumberland, must have made for a fantastic sight.

Grey Phalaropes breed across the Arctic and, unusually for a wader species, spend the winter in large gatherings at sea, off the coasts of western Africa, South America, and the southern United States. Ocean upwellings in these tropical and subtropical regions bring food to the surface of the sea, ideal conditions for the phalaropes’ feeding strategy: these dainty waders swim rapidly in tight circles, generating a whirlpool and plucking small invertebrates caught up by this movement from the edge of the vortex.

Wildfowl continued to arrive, with the northerly winds during the first part of last weekend providing ideal conditions for their movements. Flocks of Pink-footed, European White-fronted, Dark-bellied Brent and Barnacle Geese were reported up and down the east coast as birds heading south from northern Europe arrived. Goldeneye, Scaup, and Long-tailed Duck numbers typically build from the end of October and through into November, and during the last week sightings for all three species increased; again, the majority of birds were reported along the east coast. Long-tailed Ducks in particular have a preference for coastal waters, but, like Goldeneye and Scaup, can also be found on freshwater lakes.

Back in early October, huge numbers of Coal Tits were recorded moving south across northern and western Europe. Among the most astonishing records was a report of 69,000 individuals passing through Hanko Bird Observatory in southern Finland on 1 October. This ‘irruption’ involves Coal Tits of the Continental subspecies Periparus ater ater; they have a bluish-grey mantle and a very slight crest compared to birds of the British and Irish subspecies P. ater britannicus.

The irruption has recently moved westward, bringing more of these delightful birds to our shores. Coal Tits are a rare find in Shetland, but during the past week over 100 have been recorded from the archipelago; this mass arrival has been a highlight of the autumn for many resident birders.

Continental Coal Tits aren’t the only birds to have arrived from further east: there have also been scattered records of ‘Northern’ Treecreepers (the Certhia familiaris familiaris subspecies) and ‘Northern’ Bullfinches (the Pyrrhula pyrrhula pyrrhula subspecies), mainly across northern parts of the UK. Indeed, a Northern Bullfinch was found in the kitchen of a Shetland house during the week!

The calmer weather in the wake of Storm Babet also allowed a good mix of other passerines to arrive from further east, or continue pushing south across the country. At some migration hotspots, it was difficult to know where to look with a steady stream of many different species passing overhead.

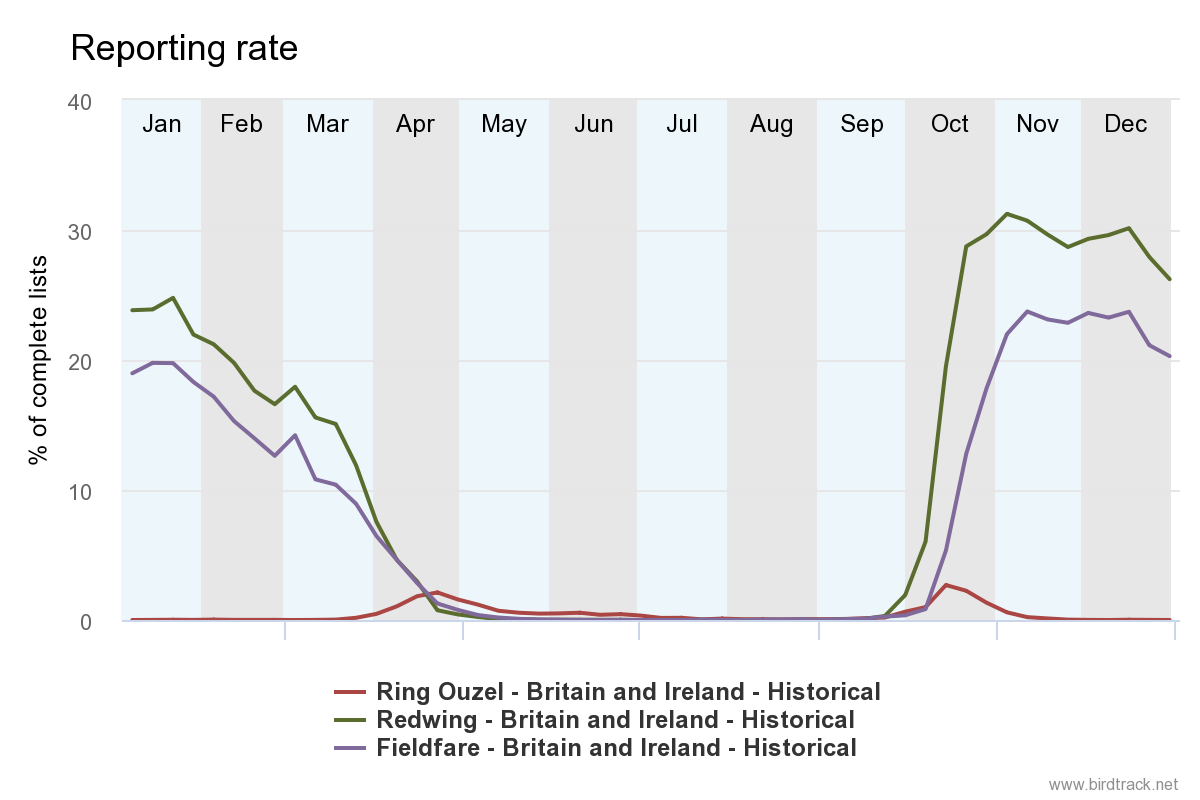

Finch species including Chaffinch, Goldfinch, Lesser Repoll, Siskin and Brambling all saw an increase in reports. Other species on the move were Meadow Pipit, Skylark, Reed Bunting, and Pied Wagtail. As is typical for this time of year, there was an increase in reports of thrush species: Blackbird, Redwing, Fieldfare, Ring Ouzel, and Mistle Thrush arrived in ever-growing numbers from Fennoscandia. Reports of both Robin and Dunnock also increased; both are species we don’t typically think of as migrants, but Continental birds do arrive here each autumn to escape the coldest of the European winters.

The high-pitched call of the Goldcrest has been a common sound in the last week too, with hundreds of these birds arriving from across the North Sea, taking advantage of the same easterly winds that brought the flocks of thrushes. These remarkable little sprites will feed almost anywhere when they arrive, with birds seen foraging in small patches of weeds and seemingly just as at home as when they are flitting through tall pine trees.

Top spots on the rarities list have to go to the Western Olivaceous Warbler – the first British record – and a Red-headed Bunting, which gave those tasked with confirming its identity quite a challenge.

As well as the more usual species, birdwatchers were delighted to see the past week produce a couple of standout rarities. Top of the list has to go to the Western Olivaceous Warbler that was found in Shetland, stayed around for a couple of days, and represents the first British record of this species. Given that this species breeds as near as southern Spain, it is surprising that it hasn’t occurred in the UK before.

A Red-headed Bunting – possibly only the second record for Britain – was spotted at Flamborough, causing some head-scratching from those who were tasked with confirming its identity. This was a challenge given how similar the species is to the closely related Black-headed Bunting, and the still-evolving criteria used to separate the two.

Looking ahead

The end of October is often considered to coincide with the end of the autumn migration period, the last roll of the dice to find a rare vagrant. In recent years, though, this window of opportunity has been pushed further into November – so there are still a few weeks remaining for you to see a range of species on the move, before winter establishes itself and birds become more sedentary.

Given the movement of birds seen last week, now would be a good time to look for Shags, especially if you live near a reservoir or large body of fresh water. Shags are slightly smaller than Cormorants and have a thinner neck and a slimmer bill that they tend to hold slightly raised, especially when swimming. Feeding birds leap out of the water to dive for fish, whereas Cormorants do this less often, preferring to just slink below the surface. You can learn more about how to separate these species in our Cormorant and Shag Bird ID video.

The weather for the coming weekend looks to be split across the country, with mixed conditions for migration. A low-pressure system will bring south-westerly winds for southern and western regions, and easterly and north-easterly winds for much of northern England and Scotland, all accompanied by frequent spells of rain.

Clearer skies, shorter days, and colder temperatures in north-western Europe will continue to signal to birds that it’s time to head south for winter – expect to see more Redwings and Fieldfares as well as finches like Bramblings, and look out for unusual passerines like Siberian Chiffchaffs.

Scotland and northern England will likely receive the majority of migrant birds from north-western Europe as clearer skies, shorter days, and colder temperatures in that region continue to signal to birds that it’s time to head south for winter. Expect another arrival of Redwings and Fieldfares, as well as more Goldcrests, and finches such as Bramblings.

Any Chiffchaff you see at this time of year is worth scrutinising: it could be a Siberian Chiffchaff Phylloscopus collybita tristis. This subspecies of the Chiffchaff breeds, as its name suggests, across the Siberian taiga, and is paler in appearance than our ‘usual’ Chiffchaff, P. collybita. Key identification features include its plumage, which is a buff colour over much of the body, the legs and bill, which are strikingly dark, and the supercilium (stripe over the eye), which lacks any yellowish tones. The Siberian Chiffchaff’s call is a short, weak “peep” that is squeakier in tone than a Chiffchaff’s more fluting, ascending “swiit”.

Common Chiffchaff call

Siberian Chiffchaff call

Each winter, our resident population of Starlings is joined by thousands of birds that fly across the North Sea from Continental Europe. Flocks of Starlings coming in low over the sea are a familiar sight for many seawatchers, but can be a bit of a surprise when first witnessed.

The main breeding grounds of the Starlings that migrate to Britain and Ireland lie approximately east-north-east, with birds coming from Norway, the Low Countries, north Germany, north Poland, and northern Russia. Many of these Continental birds will stay here until March or April before they complete their annual migration cycle and head westward.

Look out for Starling murmurations in the coming weeks – these large, swirling flocks are indubitably a spectacle of nature in winter, and can in fact contain birds from all across northern Europe!

Any calmer spells of weather during the next week should see the rest of passerine migration continue, with finches and thrushes again making up the bulk of the birds on the move. You don’t need to go far to witness this, as birds will be mobile across a wide front. It’s also worth listening out for the calls of birds overhead, as many announce their presence this way.

Sitting in the garden with a cup of tea could result in watching a nice variety of species flying over; why not see how many you can record in 20 minutes?

Send us your records with BirdTrack

Help us track the departures and arrivals of migrating birds by submitting your sightings to BirdTrack.

It’s quick and easy, and signing up to BirdTrack also allows you to explore trends, reports and recent records in your area.

Find out more

Share this page