Willow Tit

Introduction

The endearing Willow Tit, generally timid with a buzz-like contact call, has suffered the worst population decline of a resident UK bird in recent times.

The Willow Tit is best separated from the Marsh Tit by its call, as these species look very alike. Habitat is also a good indicator; Willow Tit prefer damp, young, regenerating woodland containing old dead wood and remain on or near their territory all year round. Adults excavate their own nest holes in April, and lay up to eight eggs in a single annual breeding attempt. Fledglings disperse a few kilometres away.

Willow Tit numbers have fallen sharply since the mid-1970s and the species has been Red-listed in the UK since 2022. It has also undergone range contraction, becoming locally extinct in many of its former haunts, especially in southern and eastern Britain. Habitat deterioration is thought to be the main driver of these changes, although this species might also be susceptible to competition from other tit species and predation pressure.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Marsh and Willow Tits

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Willow Tits have been in decline since the mid 1970s, and have become locally extinct in an ever-growing number of former haunts. The UK conservation listing was upgraded from amber to red in 2002. Atlas surveys during 2008-11 found that the species had virtually disappeared from the southeastern part of its English range since 1988-91 (Balmer et al. 2013). The continuing decline in the CBC/BBS index through the 1990s, following a brief period of stability during the 1980s, is replicated in the CES abundance trend. All UK breeding records since 2010 should be forwarded to the Rare Breeding Birds Panel, who have developed specific recording criteria. Willow Tit has shown a decline across Europe since 1980, but has declined to a lesser extent in central and eastern Europe than in the north, west and south (PECBMS: PECBMS 2007, PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

Owing to historic declines, by 2007–11 the distribution of Willow Tits was concentrated in a crescent from northeast England to south Wales with several scattered outposts. The species is very sedentary so, not surprisingly, the winter and breeding distributions closely match one another. Declines continue and some outlying populations on these maps may no longer exist.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Willow TIts have virtually disappeared from the southeastern part of their English range since 1988–91. Apparent hot spots in southern England, East Anglia and the southern Midlands have vanished in the space of just two decades. Despite a rather constant population decline, range loss accelerated from 10% between the 1968–72 Breeding Atlas and the 1988–91 Breeding Atlas to 50% subsequently and has likely continued.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

Willow Titi is a localised and declining resident, recorded throughout the year.

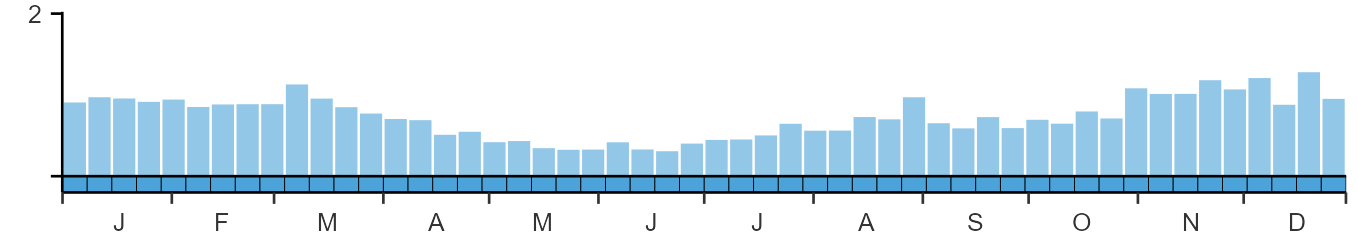

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

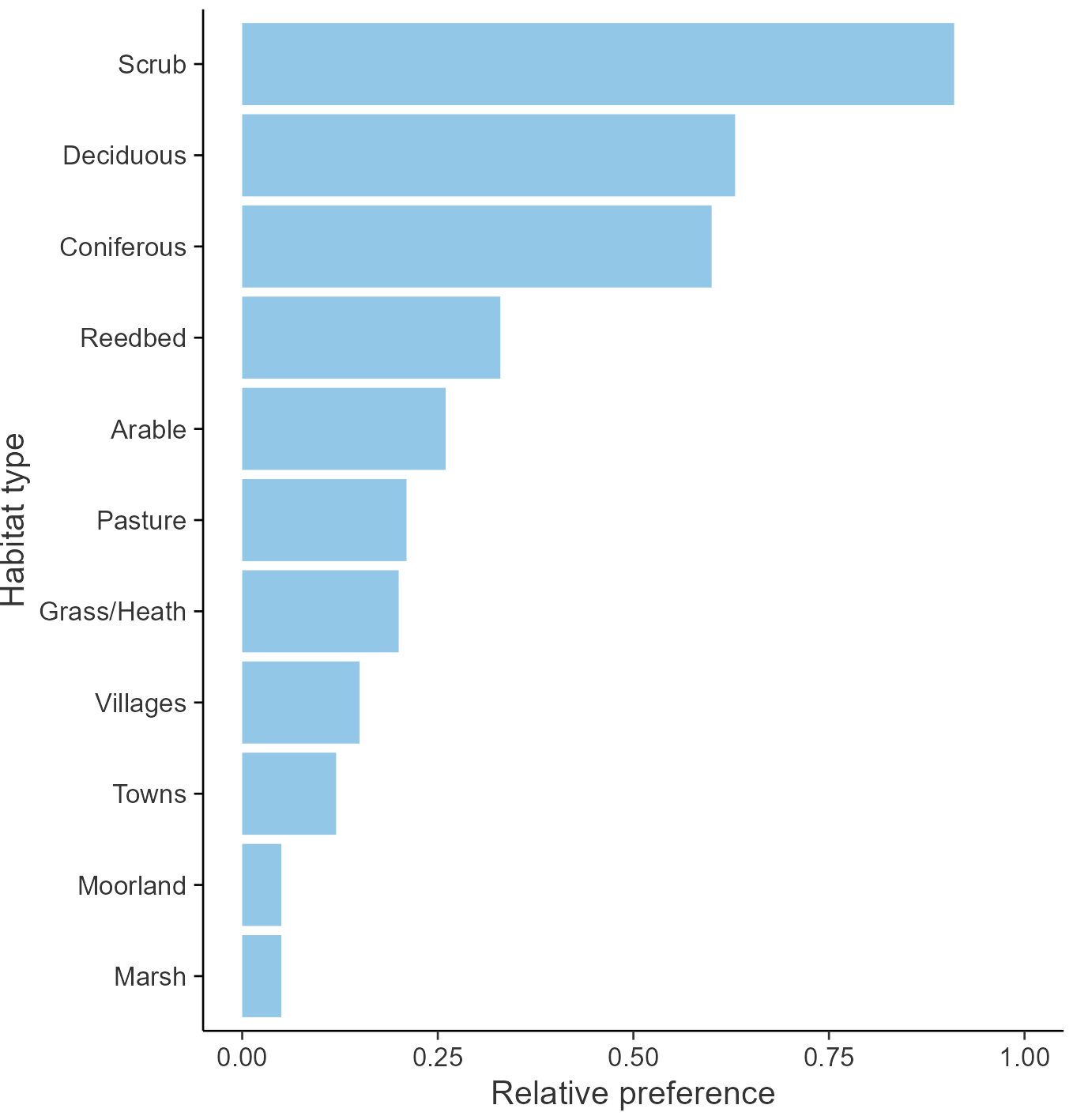

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Paridae

- Scientific name: Poecile montanus

- Authority: von Baldenstein, 1827

- BTO 2-letter code: WT

- BTO 5-letter code: WILTI

- Euring code number: 14420

Alternate species names

- Catalan: mallerenga capnegra

- Czech: sýkora lužní

- Danish: Fyrremejse

- Dutch: Matkop

- Estonian: põhjatihane

- Finnish: hömötiainen

- French: Mésange boréale

- Gaelic: Cailleachag-sheilich

- German: Weidenmeise

- Hungarian: kormosfeju cinege

- Icelandic: Votmeisa

- Italian: Cincia alpestre

- Latvian: peleka zilite

- Lithuanian: šiaurine pilkoji zyle

- Norwegian: Granmeis

- Polish: czarnoglówka (zwyczajna)

- Portuguese: chapim-montês

- Slovak: sýkorka ciernohlavá

- Slovenian: gorska sinica

- Spanish: Carbonero montano

- Swedish: talltita

- Welsh: Titw'r Helyg

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

Willow Tits have declined in woodland, probably because of habitat degradation. How this relates to demographic trends is unclear.

Further information on causes of change

Little evidence is available regarding changes in the demography of this species but CES trends suggest a decline in productivity since 1983 (see above). Lampila et al. (2006) found that adult survival was the main driver of Willow Tit populations in northern Finland, although a study in Norway recorded adult survival of around 50% (Hogstad & Slagsvold 2018) which is in line with the survival rates for Blue Tit and Great Tit published in this report. Both these studies were in boreal forests, so the processes may not be the same as for the British population. The British subspecies shows very different habitat preferences to the Fennoscandian one, preferring wet woodland rather than conifers, emphasising that Continental studies may not be very relevant to population change in the UK.

There are several hypotheses that have been put forward to explain the cause of population declines of Willow Tit. One is that deterioration in the quality of woodland as feeding habitat for this species through canopy closure and increased browsing by deer (Perrins 2003, Siriwardena 2004, Fuller et al. 2005, Newson et al. 2012) has been important. The area of wet woodland and scrub is also thought to have declined as a result of drainage and the occurrence of increasingly dry summers (Vanhinsbergh et al. 2003). A field study based on former CBC sites and other woods that were known to have held the species in the past provided good evidence that the sites still holding Willow Tit tended to be wetter, so drying out of woodlands may have been a factor (Lewis et al. 2007, 2009a, 2009b). Siriwardena (2004) analysed long-term CBC trends and found that, although population trends have been stable in their preferred, wet habitats, Willow Tit have declined in woodland, probably because of habitat degradation.

A second hypothesis is that nest predation pressure, from Jays, Great Spotted Woodpeckers and grey squirrel, for example, has increased, both because some of these predators have grown more abundant (Harris et al. 1995, this report) and because restrictions in nest-site availability are likely to have forced more birds into suboptimal, more vulnerable sites. In the study mentioned above, Siriwardena (2004) found increases in Green Woodpecker abundance on CBC plots at the same time as declines in Willow Tit abundance, but this is unlikely to reflect a causal link - this woodpecker being unrecorded as a nest predator. A negative relationship between Great Spotted Woodpecker and Willow Tit abundance on farmland plots is more likely to reflect a real population effect, but farmland is only a minor habitat for the species, so it is unlikely that such a relationship has biological significance for Willow Tits nationally. There were no significant associations with other avian potential nest predators. Supporting this result, Lewis et al. (2007, 2009a, 2009b) found that sites that were known to have held the species in the past and that were still holding Willow Tits did not differ in the density of potential nest predators. In a study which monitored 128 nests over 2014-18 in Greater Manchester, predation accounted for 60% of the 45% of nests that fai

Thirdly, increases in the local populations of behaviourally dominant, sympatric species such as Blue Tit, Great Tit, Marsh Tit and Nuthatch could have led to increased competition, especially for nest-holes. There is little direct evidence specifically concerning foraging interactions involving Willow Tit in the UK but it is possible that increases in other tit species have placed extra pressure on Willow Tit populations through competition for food or nest sites (Vanhinsbergh et al. 2003). In Lanarkshire, central Scotland, Great and Blue Tits were found commonly to take over the nest sites of Willow Tit (Maxwell 2002, 2003) but it is unclear how widespread this phenomenon is. In the Greater Manchester study mentioned above (Parry & Broughton 2019), eviction by Blue Tits caused 23% of first breeding attempts to fail, but only 3% of second attempts, so the ability to re-lay may limit population level effects of usurpation. Excluding evicted and predated nests, 98% of eggs in this study resulted in fledged chicks, suggesting that competition for food was not an issue at this site, at least during the nestling stage. In the analysis of long-term CBC trends carried out by Siriwardena (2004), no negative relationships were found between Willow Tit and its potential competitors. Again, this was supported by field data from Lewis et al. (2007, 2009a, 2009b), who found that sites that were known to have held the species in the past and that that were still holding Willow Tits did not differ in the density of avian competitors.

Overall, therefore, habitat deterioration is the strongest candidate as the cause of Willow Tit decline nationally. As well as increasing woodland drainage, degradation has been hypothesised to have occurred via a reduction in nest-site availability resulting from falls in the amount of dead wood and number of dead trees in woodland reducing nesting opportunities (Vanhinsbergh et al. 2003). This has yet to be tested formally, however, probably because historical data on quantities of dead wood are not available.

Information about conservation actions

The long-term decline of this species is most likely to have been caused by habitat degradation, and hence conservation actions and policies which aim to restore and create habitat are most likely to benefit this species.

Wet woodland also seems to be a particularly important habitat for Willow Tits, and one study found that soil water content was the only significant difference between sites which were still occupied and those which had been abandoned. This study concluded that "Habitat provision for Willow Tit should involve provision of young woodland patches with moist soils" (Lewis et al. 2009a). Another study identified deadwood of silver birch, elder and alder as the most frequent trees used for nest sites (Parry & Broughton 2019). Deterioration of the woodland understorey is also believed to be important (see Causes of Change section, above); actions to promote understorey habitat could include management to create a more open canopy and to control deer numbers.

It is also possible that increased interspecific competition for food and nest sites might be having some negative effects on local Willow Tit numbers, although the evidence does not suggest that this is likely to be the main cause of the general population decline. Nevertheless, it might be prudent to discourage the increased provision of food and nest boxes within and near Willow Tit strongholds as a precaution.

Publications (2)

The benefits of protected areas for bird population trends may depend on their condition

Author:

Published: 2024

BTO-led research highlights the importance of the quality of protected areas in their effectiveness.

28.03.24

Papers

The State of the UK's Birds 2020

Author:

Published: 2020

The State of UK’s Birds reports have provided an periodic overview of the status of the UK’s breeding and non-breeding bird species in the UK and its Overseas Territories since 1999. This year’s report highlights the continuing poor fortunes of the UK’s woodland birds, and the huge efforts of BTO volunteers who collect data.

17.12.20

Reports State of the UK's Birds

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).