Ringed Plover

Introduction

This smart, small wader can be found around most of our coast, though is less commonly encountered in the south-west of England and western Wales.

Inland breeding also occurs, with pairs favouring disused gravel bits, river margins and, in Ireland, harvested peat bogs. Flooded gravel pits provide ideal breeding habitat for this beach denizen. On beaches, however, the story is less rosy, with disturbance from increasing visitor numbers reducing breeding success.

Adult Ringed Plover are distinctive with their black 'bandit' eye-masks and orange legs. When nesting, individuals will feign a broken-wing to draw predators away from the chicks. The chicks are perfectly camouflaged against their sandy substrate, so will sit and 'hide' if they can as they are near impossible to spot.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Ringed Plovers

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

The breeding population is monitored at intervals by special surveys. A BTO survey in 1984 showed increases throughout the UK since the previous survey in 1973-74 (Prater 1989). The spread of the breeding distribution inland between the first two atlas periods, especially in England, was probably associated with the increase in number of gravel pits and reservoirs (Gibbons et al. 1993). Surveys in England and Wales revealed an increase of 12% in breeding birds in wet meadows between 1982 and 2002 (Wilson et al. 2005). The BTO's repeat national survey in 2007 found an overall decrease in UK population of around 37% since 1984, with the greatest decreases in inland areas (Burton & Conway 2008, Conway et al. 2019).

Wintering numbers have been in decline since the late 1980s, although they have remained stable since around 2010/11 (WeBS: Frost et al. 2020). Through these winter declines, the species moved from amber to being red listed in the latest review (Eaton et al. 2015).

Distribution

Wintering Ringed Plovers are widely distributed round the coasts of the UK, with small numbers recorded inland, mainly across northern and eastern England and some may be early returning breeders. The breeding distribution is mainly coastal, with significant gaps only in southwest England, Yorkshire, and southwest Wales. Inland breeding occurs in a range of mainly wetland habitats including along rivers, by lochsides and gravel pits.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

There has been a 23% range contraction in Ireland and a 5% expansion in Britain since the 1968–72 Breeding Atlas.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

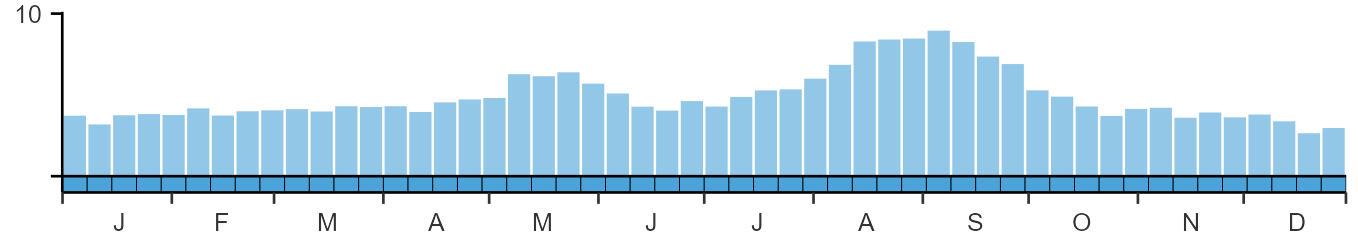

Seasonality

Ringed Plovers are recorded year-round though with peaks associated with migration of northern breeding populations.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Charadriiformes

- Family: Charadriidae

- Scientific name: Charadrius hiaticula

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: RP

- BTO 5-letter code: RINPL

- Euring code number: 4700

Alternate species names

- Catalan: corriol anellat gros

- Czech: kulík písecný

- Danish: Stor Præstekrave

- Dutch: Bontbekplevier

- Estonian: liivatüll

- Finnish: tylli

- French: Pluvier grand-gravelot

- Gaelic: Trìlleachan-tràghad

- German: Sandregenpfeifer

- Hungarian: parti lile

- Icelandic: Sandlóa

- Irish: Feadóg Chladaigh

- Italian: Corriere grosso

- Latvian: smilšu tartinš, dudievinš

- Lithuanian: jurinis kirlikas

- Norwegian: Sandlo

- Polish: sieweczka obrozna

- Portuguese: borrelho-grande-de-coleira

- Slovak: kulík piesocný

- Slovenian: komatni deževnik

- Spanish: Chorlitejo grande

- Swedish: större strandpipare

- Welsh: Cwtiad Torchog

- English folkname(s): Sea/Sand Lark

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The main drivers of change for Ringed Plover are uncertain; however increases in disturbance and predation may have contributed to the observed marked increase in nest failures at the egg stage.

Further information on causes of change

The 1984 survey revealed that over 25% of the UK population nested on the Western Isles, especially on the machair, but breeding waders there have subsequently suffered greatly from predation by introduced hedgehogs (Jackson et al. 2004) - a problem that appears increasingly severe (Jackson 2007). There was a marked decline in breeding numbers of Ringed Plovers in the Uists between 1983 and 2014, evident in areas both with and without hedgehogs (Calladine et al. 2015). Soil fertility also appears to be an issue: for the most important populations on the Uist machair in areas without hedgehogs, declines were associated with reduced soil fertility (Calladine et al. 2014b) and also lower calcium carbonate concentrations in dune systems (Fuller 2018)

Ringed Plovers that choose beaches for nesting are especially vulnerable to disturbance, however, and already in 1984 were largely confined in some regions to wardened reserves (Prater 1989). Human usage of beach areas severely restricts the availability of this habitat to nesting plovers (Liley & Sutherland 2007). There has been a marked increase in nest failures at the egg stage.

Information about conservation actions

Ringed Plovers nesting on beaches are especially vulnerable to disturbance and this restricts the availability of nesting habitat (Prater 1989; Liley & Sutherland 2007). Therefore, actions which reduce human recreational disturbance at selected sites may be important. Preventing nest loss from human activity (e.g. by fencing nests) is predicted to increase the population by 8% and complete absence of human presence (i.e. exclusion from beaches) to increase the population by 85% (Liley & Sutherland 2010).

Where disturbance is minimal, removing some vegetation to create suitable habitat for plovers can potentially also increase the number of plovers nesting in an area, based on one experimental study in Lancashire (Wilson 2005). On machair habitat in the Uists,they may benefit from rotational cultivation which includes both plough and fallow stages (Fuller 2018)

Predation may also be important at some sites and therefore predation control may be required. For example, introduced hedgehogs are believed to be an issue on the Western Isles (Jackson et al. 2004; Jackson 2007; Calladine et al. 2017). Protection of individual nests from predators could also improve nest success: Provision of wire mesh cages placed over nests has been shown to protect the closely related little ringed plover Charadrius dubius from predation (Gulickx & Kemp 2007), although cages can sometimes also attract attention from more intelligent predators (Colwell & Haig 2019).

Although focused on Charadrius plovers as a group and not specifically on Ringed Plovers, Colwell & Haig (2019) discuss a number of further potential conservation actions such as managing human behaviours (e.g. signage to educate visitors; prompt litter and road kill removal to reduce presence of predators); managing habitats; and lethal and non-lethal predator managements (e.g. conditioned taste aversion, scare tactics and translocation).

Publications (4)

Changes in breeding wader populations of the Uist machair and adjacent habitats between 1983 and 2022

Author:

Published: 2023

Periodic surveys of machair and associated habitats on the west coast of North Uist, Benbecula and South Uist have documented marked changes in the composition of an important breeding wader assemblage. Within the study area of there was a 25% decline in the total number of breeding waders recorded between 1983 and 2022.

15.06.23

Papers

Sensitivity mapping for breeding waders in Britain: towards producing zonal maps to guide wader conservation, forest expansion and other land-use changes. Report with specific data for Northumberland and north-east Cumbria

Author:

Published: 2021

Breeding waders in Britain are high profile species of conservation concern because of their declining populations and the international significance of some of their populations. Forest expansion is one of the most important, ongoing and large-scale changes in land use that can provide conservation and wider environmental benefits, but also adversely affect populations of breeding waders. We describe models to be used towards the development of tools to guide, inform and minimise conflict between wader conservation and forest expansion. Extensive data on breeding wader occurrence is typically available at spatial scales that are too coarse to best inform waderconservation and forestry stakeholders. Using statistical models (random forest regression trees) we model the predicted relative abundances of 10 species of breeding wader across Britain at 1-km square resolution. Bird data are taken from Bird Atlas 2007–11, which was a joint project between BTO, BirdWatch Ireland and the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club, and modelled with a range of environmental data sets.

09.12.21

BTO Research Reports

Breeding populations of Little Ringed Plover Charadrius dubius and Ringed Plover Charadrius hiaticula in the United Kingdom in 2007

Author:

Published: 2019

Newly published research by BTO has shed light on the differing fortunes of two small wading bird species breeding in the UK. Little Ringed Plover first bred in the UK in Hertfordshire in 1938. Breeding numbers have increased steadily since, accompanied by a range expansion to the north and west. The species is Green-listed in the UK Birds of Conservation Concern. The Ringed Plover, by contrast, is on the UK Birds of Conservation Concern Red list. Both species were surveyed in 1984, and again in 2007. The new study estimated that the number of Little Ringed Plover breeding in the UK had risen by 71% between 1984 and 2007, to 1,239 pairs. The species’ core range remained in England, although breeding pairs have spread further into Wales, northern England and south and east Scotland. Gravel and sand pits were the favoured habitat for Little Ringed Plover, but its relative importance had declined compared to 1984. The species’ use of shingle habitat had grown, following range expansion into northern and western regions. Over the same time period, the breeding population of Ringed Plover in the UK was estimated to have fallen by 37%, to 5,438 pairs. The greatest declines were reported in England and Scotland, with numbers more stable in Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man. Decreases were marked in both coastal and inland areas, including at sites where Little Ringed Plover numbers had increased. The two species have similar inland habitat preferences, so the reasons underlying the different trends are not clear. Potential factors contributing to the decline in Ringed Plover at coastal sites include disturbance from human recreational activities as well as habitat change elsewhere. Although the UK populations of both species appear have stabilised recently, greater conservation and protection efforts are required at coastal sites to ensure local breeding numbers are prevented from dropping further.

22.01.19

Papers

Consequences of population change for local abundance and site occupancy of wintering waterbirds

Author:

Published: 2017

Protected sites for birds are typically designated based on the site’s importance for the species that use it. For example, sites may be selected as Special Protection Areas (under the European Union Directive on the Conservation of Wild Birds) if they support more than 1% of a given national or international population of a species or an assemblage of over 20,000 waterbirds or seabirds. However, through the impacts of changing climates, habitat loss and invasive species, the way species use sites may change. As populations increase, abundance at existing sites may go up or new sites may be colonized. Similarly, as populations decrease, abundance at occupied sites may go down, or some sites may be abandoned. Determining how bird populations are spread across protected sites, and how changes in populations may affect this, is essential to making sure that they remain protected in the future. These findings come from a new study by Verónica Méndez and colleagues from the University of East Anglia working with BTO. Using Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS) data the study looked at changes in the population sizes and distributions of 19 waterbird species across Britain during a period of 26 years and their effect on local abundance and site occupancy. Some of these species saw steady increases in population size (up to 1,600%, Avocet), whereas other saw mild declines (-26%, Purple Sandpiper and Shelduck). The results showed that changes in total population size were predominantly reflected in changes in local abundance, rather than through the addition or loss of sites. This is possibly because waterbirds tend to be long-lived birds, with high site fidelity and new suitable sites may not always be available. Thus colonisation of new sites may typically occur when their existing sites approach their maximum capacity. As changes in populations are largely manifested by changes in local abundance – and as sites are often designated for many species – the numbers of sites qualifying for site designation are unlikely to be affected. Understanding the dynamic between population change and change in local abundance will be key to ensuring the efficiency of protected area management and ensuring that populations are adequately protected. Data from the Wetland Bird Survey and its predecessor schemes, which are celebrating 70 years of continuous monitoring of waterbirds this year, have been integral to both the designation of protected sites and monitoring of their condition. Continuation of this monitoring through future generations will ensure that the impacts to waterbird populations of future environmental changes may be understood.

20.09.17

Papers

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).