Song Thrush

Introduction

The Song Thrush lives up to its name and is a consummate singer. It is often heard at first light and as darkness falls at the end of the day.

The Song Thrush is essentially a woodland bird that has adapted to use our parks and gardens for feeding and breeding. It is known for its habit of hitting snails against a rock to break the shell and access the soft-bodied prey within; piles of broken snail shells are a good indicator of a bird's presence.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the population underwent a steep decline and many British gardens lost their resident Song Thrush. More recently, there have been signs of a slight recovery. Song Thrushes breed throughout Britain & Ireland. It is also a migrant species, with birds from northern Europe arriving during the late autumn. Some will spend the winter in Britain & Ireland whilst others will head further south as far as North Africa.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Nightingale and Other Night Singers

#BirdSongBasics: Song Thrush and Mistle Thrush

#BirdSongBasics: Blackbird and Song Thrush

Song Thrush and Mistle Thrush

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Alarm call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

CBC/BBS showed a steep decline in Song Thrush abundance that began in the mid 1970s. Short-term increases beginning around 2012 mean that the long-term UK decline is now classed as moderate rather than steep, but the population remains substantially lower than in the late 1960s. The latter part of this decline and the recent slight increase can also be seen in the CES index. BBS data from all UK countries show increase from 1995 to 2008, followed by a sharp downturn from 2008 to 2012 and the subsequent increase, but population levels remained relatively low throughout and numbers have again dropped slightly in the two most recent years. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that increase over that period was strongest in Wales and northern England, with little change in Northern Ireland and southeastern England. An increase has occurred across Europe since 1980, following declines in the early 1980s which have since been reversed (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

Song Thrushes were recorded in 94% of 10-km squares in the breeding season and 92% of squares in winter during 2007–11. They were absent only from parts of the Scottish Highlands and Southern Uplands during the winter months. Densities are distinctly higher in Ireland than in Britain in both seasons and abundance is generally greatest in low-lying areas.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

There has been little change in Song Thrush breeding distribution since the 1970s despite large population declines. A more recent small population increase is matched by atlas abundance change maps which indicate an increase in relative abundance in Ireland, Wales, central and southwestern England since the 1988–91 Breeding Atlas.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

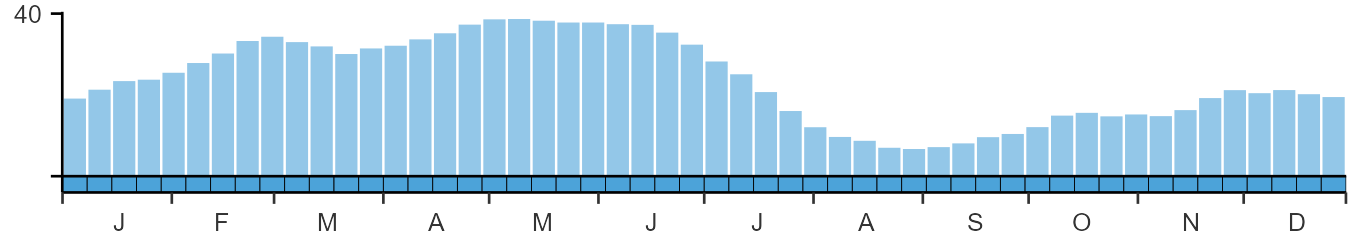

Song Thrush is widely recorded throughout the year, especially in late winter and spring when easily detected by song.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

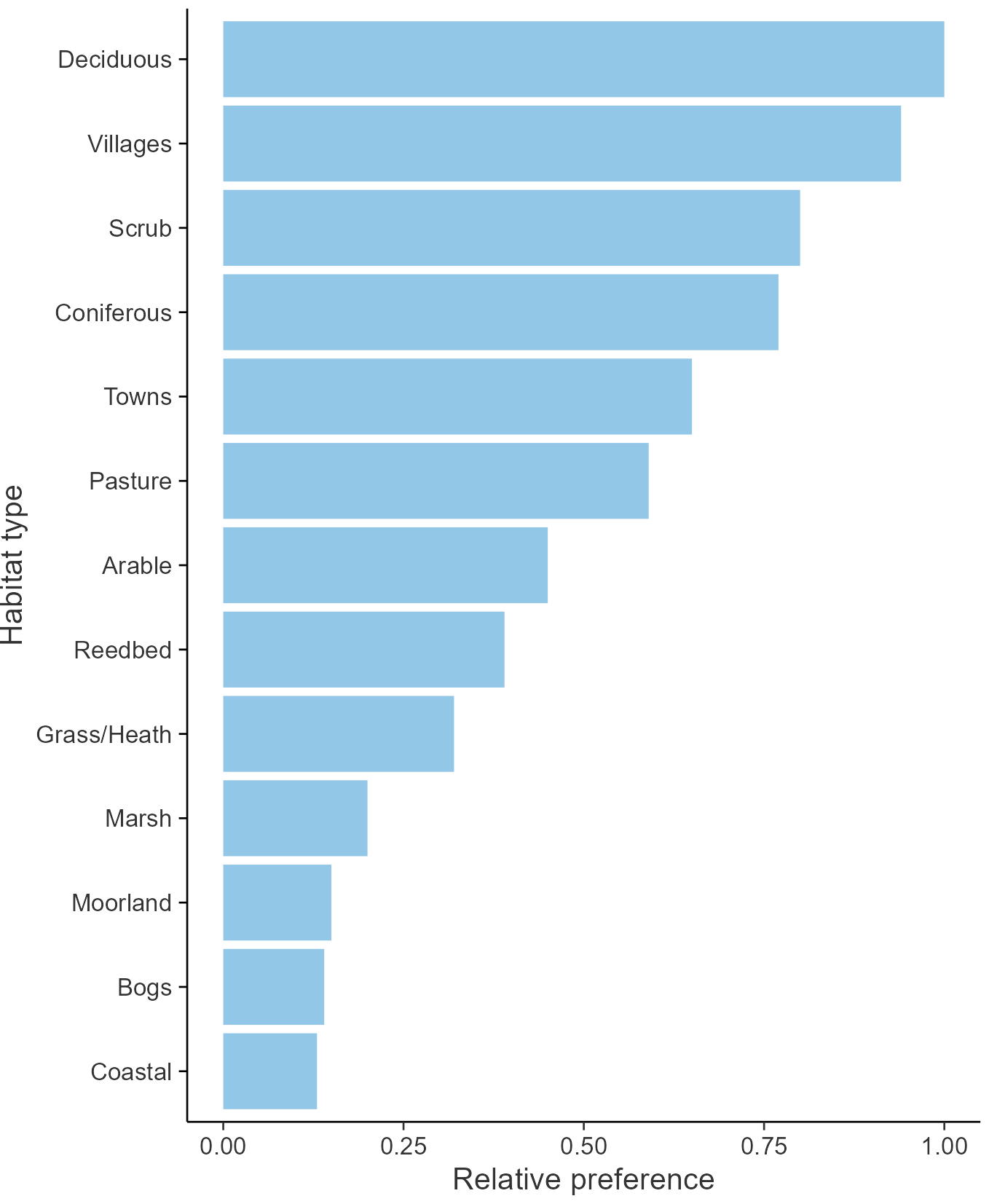

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Turdidae

- Scientific name: Turdus philomelos

- Authority: CL Brehm, 1831

- BTO 2-letter code: ST

- BTO 5-letter code: SONTH

- Euring code number: 12000

Alternate species names

- Catalan: tord comú

- Czech: drozd zpevný

- Danish: Sangdrossel

- Dutch: Zanglijster

- Estonian: laulurästas

- Finnish: laulurastas

- French: Grive musicienne

- Gaelic: Smeòrach

- German: Singdrossel

- Hungarian: énekes rigó

- Icelandic: Söngþröstur

- Irish: Smólach Ceoil

- Italian: Tordo bottaccio

- Latvian: dziedatajstrazds, macinš

- Lithuanian: strazdas giesmininkas

- Norwegian: Måltrost

- Polish: (drozd) spiewak

- Portuguese: tordo-pinto

- Slovak: drozd plavý

- Slovenian: cikovt

- Spanish: Zorzal común

- Swedish: taltrast

- Welsh: Bronfraith

- English folkname(s): Mavis

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

Changes in survival in the first winter, and also the post-fledging period, are sufficient to have caused the population decline. The environmental causes of this are unknown but are likely to include changes in farming practices, particularly land drainage and possibly increased pesticide usage.

Further information on causes of change

CES productivity shows an initial decrease, followed by fluctuations around a new lower level, and the number of fledglings per breeding attempt increased during the 1980s and 1990s but has since decreased (see above). There is good evidence to show that changes in survival in the first winter have contributed to the population decline (Thomson et al. 1997, Siriwardena et al. 1998b, Robinson et al. 2004). A more recent integrated analysis also indicated that post-fledging survival also made some contribution to annual population changes (Robinson et al. 2014).

Peach et al. (2004) suggested that loss of hedgerows, scrub and permanent grassland with livestock and the widespread installation of field drainage systems, all of which would act to reduce the availability of good quality foraging areas, have probably contributed to the decline of the Song Thrush in the UK. Similarly, it has been suggested that the species is unable to survive the winter in woodland, due to a lack of food, and a reduction of food supply in other habitat types has also been reported (Simms 1989). It is likely that a reduction in food supply would adversely affect the survival of juvenile birds to a greater extent than adult birds, as appears to be the case (Robinson et al. 2004). Furthermore, survival is reduced during periods of long drought or cold weather when food is likely to be less available (Robinson et al. 2007). However, modelling suggests that climate change may have had a positive impact on the long-term trend for this species, resulting in less negative trends than would have occurred in the absence of climate change (Pearce-Higgins & Crick 2019).

In woodland, drainage of damp ground and the depletion of woodland shrub layers through canopy closure and deer browsing may also be implicated (Fuller et al. 2005). There is also some concern of the impact of overgrazing by deer (e.g. Gill & Beardall 2001) and canopy closure (Mason 2007), due to changes in woodland management (Hopkins & Kirby 2007) on the low woodland layers, although good evidence from the UK is sparse (but there are some experimental studies in America on different species which demonstrate this effect, e.g. McShea & Rappole 2000). A study based on BBS results from 1995 to 2006 found a negative correlation between the abundance of deer and Song Thrush, with the species declining the most where deer population increase had been greatest, although the size of the impact was relatively small with modelling suggesting that deer could have caused a decline of around 4% over this period (Newson et al. 2012). Several papers (e.g. Gosler 1990, Perrins & Overall 2001, Perrins 2003) state that the understorey has declined in Britain, but few data are available to support this on a national scale. However, Amar et al. (2006) found a 27% increase in understorey in the RSPB sites used in the Repeat Woodland Bird Survey.

Robinson et al. (2004) suggested that predation was a possible cause of reduced survival but there is conflicting evidence on the role of predators in Song Thrush decline, and further research is needed. Newson et al. (2010b) found no evidence of effects of avian predators or grey squirrels on Song Thrushes.

Information about conservation actions

Like its close relative the Blackbird , the Song Thrush declined substantially during the 1970s and 1980s. Numbers have subsequently remained low despite recent slight increases. The decline was probably caused by changes to post-fledging and first winter survival and hence actions to increase food availability may benefit Song Thrush. These could include providing supplementary food over winter, managing hedgerows or woodland habitat for wildlife, and providing additional habitat, e.g. wild bird seed or cover mixtures, set-aside or grass buffer strips/margins.

As well as the removal of habitat such as hedgerows and scrub, loss of livestock (along with associated grasslands) and field drainage may also have reduced the amount of good quality foraging habitat, with field drainage being linked to the availability of earthworms (Peach et al. 2004). Peach et al. (2004) recommended that "new policy initiatives should aim to restore nesting cover (scrub and woodland understorey), grazed grasslands in arable dominated areas and damper soils in summer". Kelleher & O'Halloran (2010) also stressed the need to provide good nesting cover as a conservation action for Song Thrush and stated that dense vegetation was important when Song Thrushes were choosing a nest-site. Management actions which could help to increase the undergrowth and ground layers include opening up the canopy and control of deer numbers.

Like Blackbird, Song Thrush is a partial migrant, and local conservation actions to support birds in winter will not necessarily benefit local populations, so changes over a large scale may hence be required in order for actions to have a significant effect on British (and European) populations.

Publications (3)

Breeding periods of hedgerow-nesting birds in England

Author:

Published: Spring 2024

Hedgerows form an important semi-natural habitat for birds and other wildlife in English farmland landscapes, in addition to providing other benefits to farming. Hedgerows are currently maintained through annual or multi-annual cutting cycles, the timing of which could have consequences for hedgerow-breeding birds. The aim of this report is to assess the impacts on nesting birds should the duration of the management period be changed, by quantifying the length of the current breeding season for 15 species of songbird likely to nest in farmland hedges. These species are Blackbird, Blackcap, Bullfinch, Chaffinch, Dunnock, Garden Warbler, Goldfinch, Greenfinch, Linnet, Long-tailed Tit, Robin, Song Thrush, Whitethroat, Wren and Yellowhammer.

05.03.24

BTO Research Reports

Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4: the population status of birds in Wales

Author:

Published: 2022

The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List, with 91 on the Amber List and just 69 - less than a third of the total number of species - on the Green List. The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales comes 20 years after the first, when the Red List was less than half the length it is today. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List in Wales, with 91 on the Amber List and 69 on the Green List. The Birds of Conservation Concern in Wales report assesses the status of each species against a set of objective criteria. Data sources include the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey and the BTO/RSPB/JNCC Wetland Bird Survey, as well as Bird Atlases and other BTO-led monitoring schemes and citizen science initiatives. These are used to quantify the changing status of the species’ Welsh population. The UK, European and global conservation status of the species is also considered, placing the Welsh population into a wider context. The Red ListSwift, Greenfinch and Rook – familiar breeding species in steep decline across the UK – are among the new additions to the Welsh Red List, which now also includes Purple Sandpiper, on account of a rapidly shrinking Welsh wintering population, and Leach’s Petrel, an enigmatic seabird in decline across its global range. These species now sit alongside well-known conservation priorities, such as Curlew, Hen Harrier and Turtle Dove as birds at risk of being lost from Wales for good. Uplands and woodlands Many of the species on the Red List are found in upland and farmland habitats. Starling, Tree Sparrow, Yellow Wagtail and Yellowhammer can no longer be found in much of Wales, while iconic species of mountain and moorland, such as Ring Ouzel, Merlin and Black Grouse, remain in serious trouble. Wales is well known for its populations of woodland birds; however, many of these – including Lesser Spotted Woodpecker, Willow Warbler and Spotted Flycatcher – also feature on the Red List. Goldcrest, which has seen its Welsh population shrink alarmingly in recent decades, is another new addition. On the coast The assessment for Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4 took place before the impacts of avian influenza could be taken into account. Breeding seabird species have been struggling in Wales for many years, however, and most were already of conservation concern before the outbreak of this disease. Kittiwake, Puffin, Black-headed Gull, and Common, Arctic and Sandwich Tern remain on the Red List. Wales holds internationally significant numbers of breeding seabirds, making the decline of these colonies a global concern. The Amber ListDeclines in Wheatear, Garden Warbler and House Martin - all migrants which breed in Europe and winter in sub-Saharan Africa - mean these species have moved from the Green List to the Amber List. Many other ‘Afro-Palearctic' migrant species are also in decline, but the potential reasons for this, such as habitat loss and reduced availability of invertebrate prey, are not well understood. Closer to home, the declines in the Welsh Chaffinch population, linked to the disease trichomonosis, have seen the species Amber-listed. A number of other species have been placed on the Amber List because of the wider importance of their Welsh populations, which in each case make up more than half the UK total. Wales is home to more than three-quarters of the UK’s Choughs, for example, so recent declines are cause for concern. The nation’s breeding populations of Manx Shearwater, Pied Flycatcher, Goshawk and Hawfinch also account for more than half the UK total, as does its wintering population of Spotted Redshank. It’s not all bad news, though: some species now on the Amber List have moved up from the Red List, indicating some positive change in their population trends. These include Common Sandpiper, Great Black-backed Gull, Bullfinch, Goldcrest and Pied Flycatcher. The Green ListWhile the report contains much cause for alarm, several conservation success stories shine through. Red Kite was almost lost as a British bird during the first half of the 20th century, when only a handful of pairs remained in remote Welsh valleys. Since then, a sustained conservation effort has brought the species back from the brink. Wales is now home to more than 2,500 pairs of Red Kite and the species has now been moved to the Green List, reflecting this incredible change in fortunes. Song Thrush, Reed Bunting, Long-tailed Tit, Redwing and Kingfisher are among the other species to have gone Green, providing much-needed hope that things can go up as well as down.

06.12.22

Reports Birds of Conservation Concern

Nocturnal flight calling behaviour of thrushes in relation to artificial light at night

Author:

Published: 2021

New research from BTO has investigated the effect of artificial light at night on birds, indicating that nocturnal migrants are attracted to more brightly lit areas. Migratory birds face many challenges during their annual movements between breeding and wintering areas. New research from BTO has investigated whether artificial light at night (ALAN) could disrupt movement patterns of migrant species, thereby adding to the pressures they face throughout their lifecycle. Migrating at night is a common migratory strategy. For example, 80% of UK summer migrants move after dark, and 40–150 million birds are estimated to cross the North Sea at night each autumn. Previous studies have shown that nocturnal migrants can be affected by ALAN, which can make them disoriented and cause them to collide with structures such as lighthouses, oil platforms and tall buildings. This problem is particularly associated with skyscrapers in North America, where mass mortality events occur each year. While UK and other European cities tend to have fewer tall buildings, it is important to establish the possible impacts of ALAN on migrant birds on both sides of the Atlantic. This study used passive acoustic monitoring devices deployed in the gardens of local birdwatchers to record the calls of nocturnally migrating thrushes (Redwing, Blackbird and Song Thrush). The selected birdwatchers’ gardens spanned a gradient of nocturnal illumination in Cambridgeshire - from the brightly lit city of Cambridge to the darker surrounding villages and countryside - and recordings were made during peak thrush migration, between late September and mid-November in 2019. The audio recordings were analysed using artificial neural networks, which had been trained to identify calls of the target species and differentiate them from other sources of nighttime noise. The results showed that thrush call rates were up to five times higher over the brightest urban areas than in the darkest villages, suggesting a strong effect of ALAN on these migratory species. Although evidence from other studies, such as those involving radar, indicates that this result can be explained by birds being attracted to brightly lit areas, it is also possible that individual birds call more often than normal in such environments if they are disorientated. This work highlights the need to better understand the effect of ALAN on birds and other wildlife, and also the potential for passive acoustic monitoring in helping to answer ecological questions. Read more about this work in a BOU blog: Are nocturnal migrants attracted to cities?

05.05.21

Papers

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).