Turtle Dove

Introduction

The Turtle Dove's purring song is a quintessential sound of the summer, but one that is getting harder to hear.

This summer visitor arrives in late April, after spending the winter months in West Africa, south of the Sahara. A farmland bird, breeding in mature hedgerows and dense thickets, the Turtle Dove has shown a rapid and steep decline in its numbers and a contraction in its UK breeding range.

Now lost from many former haunts, including many within its East Anglian stronghold, there is every chance of us losing the Turtle Dove as a breeding species.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Collared & Turtle Dove

Songs and Calls

Song:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

The CBC/BBS trend shows severe declines in Turtle Dove abundance, beginning in the late 1970s and continuing steeply to the present. Atlas data show that more than half the 10-km squares occupied in 1968-72 had been lost by 2008-11, with the population withdrawing towards East Anglia and Kent (Balmer et al. 2013). These trends, unless halted or reversed, would bring the species close to extinction in the UK within the next two decades and all breeding records since 2018 should be submitted to the RBBP, following the addition of Turtle Dove to the RBBP species list. There has been decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>) and the species is now classed by IUCN as globally threatened (Vulnerable).

Distribution

Breeding Turtle Doves are restricted to the eastern half of England as far north as Yorkshire and west to the Severn.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

The change map illustrates the progressive loss of range in the north, west and southwest of Britain over the last 40 years. The loss in the Home Counties is also notable. The halving of range has been accompanied by a population decline of over 90%.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

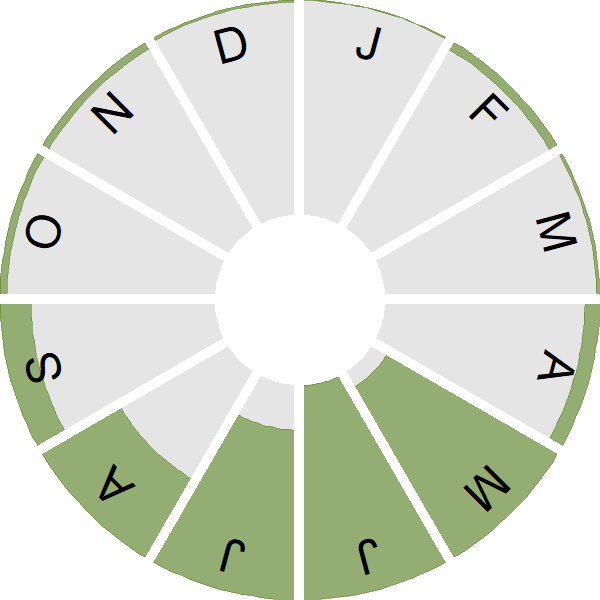

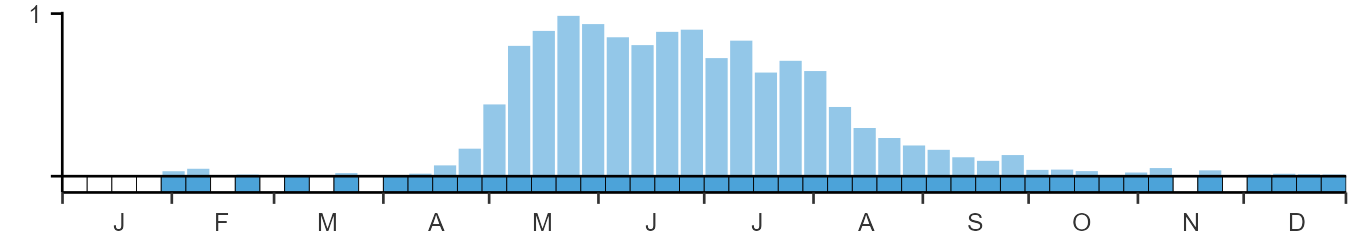

Seasonality

Turtle Doves are summer visitors, arriving gradually from mid April with reporting tailing off through summer; most birds usually departed by September but occasional birds winter.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Columbiformes

- Family: Columbidae

- Scientific name: Streptopelia turtur

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: TD

- BTO 5-letter code: TURDO

- Euring code number: 6870

Alternate species names

- Catalan: tórtora eurasiàtica

- Czech: hrdlicka divoká

- Danish: Turteldue

- Dutch: Zomertortel

- Estonian: turteltuvi

- Finnish: turturikyyhky

- French: Tourterelle des bois

- Gaelic: Turtar

- German: Turteltaube

- Hungarian: vadgerle

- Icelandic: Turtildúfa

- Irish: Fearán

- Italian: Tortora selvatica

- Latvian: ubele

- Lithuanian: paprastasis purplelis

- Norwegian: Turteldue

- Polish: turkawka (zwyczajna)

- Portuguese: rola-brava

- Slovak: hrdlicka polná

- Slovenian: divja grlica

- Spanish: Tórtola europea

- Swedish: turturduva

- Welsh: Turtur

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

There is good evidence to support the hypothesis that the primary demographic driver of Turtle Dove declines is a shortened breeding period, which has reduced the number of nesting attempts. This is thought to be driven by reduced food availability due to increased herbicide use, although analyses that test this directly are lacking. Note, however, that data do not permit analyses of variation in annual survival rates, but mortality both on the wintering grounds (due to habitat deterioration) and on migration (particularly through hunting) could be important.

Further information on causes of change

A four-year intensive field study in East Anglia provided good evidence that the role of breeding productivity in the decline of Turtle Doves is likely to be through a reduction in the average number of nesting attempts per pair (Browne & Aebischer 2005). Browne & Aebischer (2003a, 2004, 2005) concluded that Turtle Doves today have a substantially earlier close to the breeding season and consequently produce fewer clutches and young per pair than they did in the 1960s. Reduced food availability due to increased herbicide use and efficacy may make birds more likely to cease breeding earlier than during the 1960s and reduce their number of nesting attempts (Browne & Aebischer 2001, 2002), although this was not specifically tested. Browne & Aebischer (2003a) state that it may be a change in phenology of Turtle Doves and their food species which has resulted in reduced availability of food supplies, although they do not support this with any specific analyses of these two factors. More recent work, using DNA analysis to assess food items consumed by nestlings, found that those in better condition were fed on a higher proportion of natural arable plant seeds rather than seed from anthropogenically grown sources such as brassicas (Dunn et al. 2018).

Loss of quality and quantity of breeding habitat are also thought to contribute to declines. Browne et al. (2004) used long-term CBC data to provide good evidence that breeding density fell in proportion to loss of nesting, rather than feeding, habitat and that changes in Turtle Dove density were positively related to changes in the amount of hedgerow and woodland edge. Dunn & Morris (2012) suggest however that, although established scrub and large hedgerows were important in retaining Turtle Dove territories, it may be foraging habitat that is limiting their distribution. A small sample (15) of fledglings tracked using radio tags were found to remain close to the nest for the first three weeks, and select seed-rich habitats on foraging trips, and heavier birds were more likely to survive, suggesting nearby foraging habitat was important both pre- and post-fledging (Dunn et al. 2016). Recent research has also investigated customized management options which might provide foraging habitat for Turtle Doves (Dunn et al. 2015).

There is good evidence to suggest that the population decline experienced by Turtle Doves breeding in Britain is not due to lower success of individual nesting attempts. Analysis of nest record cards and ringing data for farmland Turtle Doves shows a non-significant increase in productivity per nesting attempt while annual survival has fallen (Siriwardena et al. 2000a, 2000b, Browne et al. 2005) so this may have also contributed to the decline. The demographic trends shown here support the view that nesting success per attempt is not the main driver of population change, with no significant changes identified in any of the measures (see above).

Turtle Dove is a quarry species in many European countries and Vickery et al. (2014) estimate that 2-4 million Turtle Doves are shot annually in southern Europe. Hunting during migration has been cited as another possible cause of the UK decline, although there is little evidence to support this (Browne & Aebischer 2004). A recent study concluded that the current levels of legal hunting in Europe are more than double the sustainable hunting rate (Lormee et al. 2019), but it is not clear how many birds originating from Britain might potentially be affected by hunting. Ring-recovery sample sizes are small and there is only weak evidence suggesting a decrease in annual survival (Siriwardena et al. 2000b). Nevertheless, survival could also have been negatively affected by a reduction in the quality of wintering habitat: this is thought to have contributed to the decline (Marchant et al. 1990) and one recent study has demonstrated a positive correlation between survival rate among breeding adults in France and food supply in West Africa, as measured by cereal production (Eraud et al. 2009). Further work on the ecology of Turtle Doves on their wintering grounds is needed to investigate the relevance of this result for UK birds. Trichomonosis, a disease widespread since 2005 that reduces fitness and survival among pigeons and other birds, has been recently observed in Turtle Doves and might therefore be a new factor in its decline (Stockdale et al. 2015).

Information about conservation actions

The most important driver of decline in the UK is believed to be a reduction in the number of breeding attempts due to low natural arable plant seed availability as a result of herbicide use. Hence actions designed to provide suitable nesting and foraging habitat are required (Browne & Aebischer 2004; Dunn & Morris 2012), particularly those that provide sufficient abundance of natural seeds throughout the breeding season (Browne & Aebischer 2003b; Dunn et al. 2016). Specific management actions might include the provision of uncropped margin or plots or set-aside, planting buffer strips around arable fields, sowing wild bird seed mixes, restoring or creating semi-natural grassland and managing hedgerows to provide nesting opportunities.

The decline has been so severe that the future of this species is precarious at a national level. Therefore, the provision of agri-environment options which pay farmers in and near the remaining strongholds for this species may be critical to encourage and enable the local habitat management actions described above: prompt and targeted action may be required to save this species as a UK breeding bird. In addition, supplementary feeding has been suggested as a potential action which could improve breeding productivity for this species; a field experiment did not find a significant positive effect from supplementary feeding, although the authors believed that the experimental sites were too small to show such an effect as Turtle Doves range widely during the breeding season (Browne & Aebischer 2002).

Publications (4)

Farming in Project Landscapes – Turtle Dove Monitoring Project, 2024 Report

Author:

Published: 2025

This report presents the results of work using static acoustic recorders, deployed between May and mid-August 2024, to provide extensive acoustic data for the Stour Valley Farmer Cluster.

04.03.25

BTO Research Reports

The status of the UK breeding European Turtle Dove Streptopelia turtur population in 2021

Author:

Published: 2023

The Turtle Dove is a summer migrant to the UK. Its numbers have fallen sharply in recent decades, and it is now one of only six globally threatened species that regularly breed in the UK.

11.09.23

Papers Bird Study

Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4: the population status of birds in Wales

Author:

Published: 2022

The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List, with 91 on the Amber List and just 69 - less than a third of the total number of species - on the Green List. The latest review of the conservation status of birds in Wales comes 20 years after the first, when the Red List was less than half the length it is today. The report assessed all 220 bird species which regularly occur in Wales. There are now 60 species of bird on the Red List in Wales, with 91 on the Amber List and 69 on the Green List. The Birds of Conservation Concern in Wales report assesses the status of each species against a set of objective criteria. Data sources include the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey and the BTO/RSPB/JNCC Wetland Bird Survey, as well as Bird Atlases and other BTO-led monitoring schemes and citizen science initiatives. These are used to quantify the changing status of the species’ Welsh population. The UK, European and global conservation status of the species is also considered, placing the Welsh population into a wider context. The Red ListSwift, Greenfinch and Rook – familiar breeding species in steep decline across the UK – are among the new additions to the Welsh Red List, which now also includes Purple Sandpiper, on account of a rapidly shrinking Welsh wintering population, and Leach’s Petrel, an enigmatic seabird in decline across its global range. These species now sit alongside well-known conservation priorities, such as Curlew, Hen Harrier and Turtle Dove as birds at risk of being lost from Wales for good. Uplands and woodlands Many of the species on the Red List are found in upland and farmland habitats. Starling, Tree Sparrow, Yellow Wagtail and Yellowhammer can no longer be found in much of Wales, while iconic species of mountain and moorland, such as Ring Ouzel, Merlin and Black Grouse, remain in serious trouble. Wales is well known for its populations of woodland birds; however, many of these – including Lesser Spotted Woodpecker, Willow Warbler and Spotted Flycatcher – also feature on the Red List. Goldcrest, which has seen its Welsh population shrink alarmingly in recent decades, is another new addition. On the coast The assessment for Birds of Conservation Concern Wales 4 took place before the impacts of avian influenza could be taken into account. Breeding seabird species have been struggling in Wales for many years, however, and most were already of conservation concern before the outbreak of this disease. Kittiwake, Puffin, Black-headed Gull, and Common, Arctic and Sandwich Tern remain on the Red List. Wales holds internationally significant numbers of breeding seabirds, making the decline of these colonies a global concern. The Amber ListDeclines in Wheatear, Garden Warbler and House Martin - all migrants which breed in Europe and winter in sub-Saharan Africa - mean these species have moved from the Green List to the Amber List. Many other ‘Afro-Palearctic' migrant species are also in decline, but the potential reasons for this, such as habitat loss and reduced availability of invertebrate prey, are not well understood. Closer to home, the declines in the Welsh Chaffinch population, linked to the disease trichomonosis, have seen the species Amber-listed. A number of other species have been placed on the Amber List because of the wider importance of their Welsh populations, which in each case make up more than half the UK total. Wales is home to more than three-quarters of the UK’s Choughs, for example, so recent declines are cause for concern. The nation’s breeding populations of Manx Shearwater, Pied Flycatcher, Goshawk and Hawfinch also account for more than half the UK total, as does its wintering population of Spotted Redshank. It’s not all bad news, though: some species now on the Amber List have moved up from the Red List, indicating some positive change in their population trends. These include Common Sandpiper, Great Black-backed Gull, Bullfinch, Goldcrest and Pied Flycatcher. The Green ListWhile the report contains much cause for alarm, several conservation success stories shine through. Red Kite was almost lost as a British bird during the first half of the 20th century, when only a handful of pairs remained in remote Welsh valleys. Since then, a sustained conservation effort has brought the species back from the brink. Wales is now home to more than 2,500 pairs of Red Kite and the species has now been moved to the Green List, reflecting this incredible change in fortunes. Song Thrush, Reed Bunting, Long-tailed Tit, Redwing and Kingfisher are among the other species to have gone Green, providing much-needed hope that things can go up as well as down.

06.12.22

Reports Birds of Conservation Concern

The risk of extinction for birds in Great Britain

Author:

Published: 2017

The UK has lost seven species of breeding birds in the last 200 years. Conservation efforts to prevent this from happening to other species, both in the UK and around the world, are guided by species’ priorities lists, which are often informed by data on range, population size and the degree of decline or increase in numbers. These are the sorts of data that BTO collects through its core surveys. For most taxonomic groups the priority list is provided by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) – the IUCN Red List comprises roughly 12,000 species worldwide and their conservation status. However, for birds in the UK, most policy makers refer to the Birds of Conservation Concern (BoCC) list, updated every six years (most recently in 2015). A new study funded by the RSPB and Natural England in cooperation with BTO, WWT, JNCC, and Game & Wildlife Trust has carried out the first IUCN assessment for birds in Great Britain. The study applied the IUCN criteria to existing bird population data obtained from datasets like the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey (BBS). The criteria take into account various factors, most notably any reduction in the size (both in abundance and range) of populations, loss of habitats key to the species, small or vulnerable population sizes, and extinction risk. Alongside this, the criteria look to see if there is a “rescue” effect – such as immigration from neighbouring populations that might boost the population’s numbers, reducing the risk of extinction. The species are then categorised into one of the threat levels below. The results of the new study show that a concerning 43% of regularly occurring species in Great Britain are classed as Threatened, with another 10% classified as Near Threatened. Twenty-three breeding or non-breeding populations of birds were classed as Critically Endangered, including Fieldfare and Golden Oriole (both possibly extinct as breeders), Whimbrel, Turtle Dove, Arctic Skua and Kittiwake, as well as non-breeding populations of Bewick’s Swan, White-fronted Goose and Smew., Over the past 200 years, seven species have gone extinct as breeders in Britain, including Serin, Temminck’s Stint and Wryneck in the past 25 years. The total percentage of threatened birds in Great Britain (43%) is high compared to that seen elsewhere in Europe (13%). Reasons for this are not entirely clear, although it may be that Britain’s island status has something to do with this, as there are fewer neighbouring “rescue” populations. Although the results from the IUCN assessment and BoCC assessment largely overlap, the IUCN assessment raises the level of concern for species such as Red-Breasted Merganser, Great Crested Grebe, Moorhen, Red-Billed Chough (all classed as Vulnerable), and Greenfinch (Endangered). These species might thus warrant closer monitoring in the near future. In contrast, the BoCC assessment identifies a number of species of concern whose declines have been more gradual but over long time periods (e.g. Skylark and House Sparrow). The authors emphasise that this assessment is not a replacement of the BoCC report, but rather that the two reports complement each other. With this new wealth of knowledge, there will hopefully be even more support for those species that need it most.

01.09.17

Papers

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).