Peregrine

Introduction

The Peregrine has a muscular, chunky profile for a falcon, and an increase in numbers and range means that has become a more common sight for birdwatchers across Britain & Ireland.

Breeding Peregrines are well studied. Having recovered from the lows of the 1960s, the long-term population trend has been one of increase, although this does mask regional differences. Lowland birds have taken advantage of urban and industrial structures for nesting (from cooling towers to cathedrals) and plentiful urban prey.

Conversely, upland Peregrine have been in decline, in part thought to be linked to ongoing persecution.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

Peregrine

Songs and Calls

Call:

Alarm call:

Begging call:

Other:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

The number of breeding pairs in the UK and Isle of Man is exceptionally well known. There is an estimate of 874 pairs for the 1930s and the population has been estimated every decade since 1961 as follows: 1961 - 385 pairs; 1971 - 489 pairs; 1981 - 728 pairs; and 1991 - 1,283 pairs (BTO/JNCC/RSPB/Raptor Study Groups; Ratcliffe 1993). In 2002, 1,437 breeding pairs were found in the UK and Isle of Man (Banks et al. 2003, 2010) though around 50 pairs were missed in Wales (Dixon et al. 2008). The latest figure, 1,769 pairs in 2014, represents a further increase of 22% overall since 2002 (Wilson et al. 2018).

Distribution

Peregrines breed in upland and coastal areas with suitable cliffs, and across much of the lowlands, where pairs will utilise quarries and man-made structures from pylons and power stations to churches and cathedrals.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Peregrine breeding range has tripled in size since 1968–72. Similarly, the winter range in Britain has doubled since the 1981–84 Winter Atlas, with gains primarily across lowland England. In Ireland a 51% winter range increase has seen expansion from the coast to the midlands.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

Seasonality

Peregrines are recorded throughout the year.

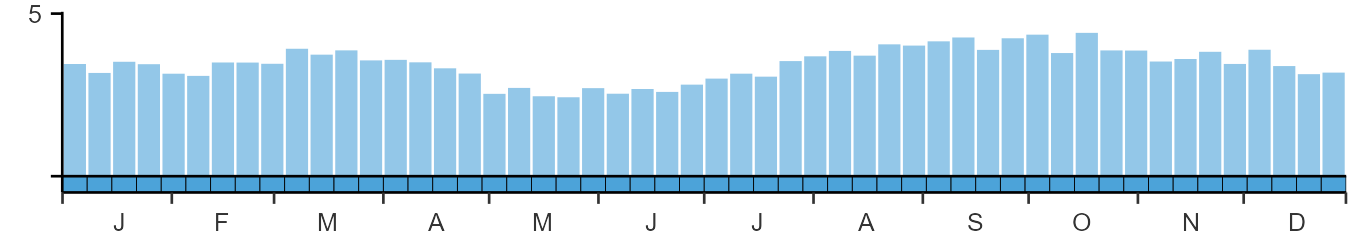

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Falconiformes

- Family: Falconidae

- Scientific name: Falco peregrinus

- Authority: Tunstall, 1771

- BTO 2-letter code: PE

- BTO 5-letter code: PEREG

- Euring code number: 3200

Alternate species names

- Catalan: falcó pelegrí

- Czech: sokol stehovavý

- Danish: Vandrefalk

- Dutch: Slechtvalk

- Estonian: rabapistrik

- Finnish: muuttohaukka

- French: Faucon pèlerin

- Gaelic: Seabhag-ghorm

- German: Wanderfalke

- Hungarian: vándorsólyom

- Icelandic: Förufálki

- Irish: Fabhcún Gorm

- Italian: Falco pellegrino

- Latvian: lielais piekuns

- Lithuanian: sakalas keleivis

- Norwegian: Vandrefalk

- Polish: sokól wedrowny

- Portuguese: falcão-peregrino

- Slovak: sokol stahovavý

- Slovenian: sokol selec

- Spanish: Halcón peregrino

- Swedish: pilgrimsfalk

- Welsh: Hebog Tramor

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The UK population size, distribution and breeding performance have all largely recovered from the poisonous effects of organochlorine pesticides in the 1950s and 1960s (Newton 2013). Illegal persecution continues to limit numbers in the uplands, and food supply may also be a limiting factor in some areas.

Further information on causes of change

Populations and breeding performance have declined, however, in northwest Scotland and the Northern Isles (Crick & Ratcliffe 1995). The overall increase between the 2002 and 2014 surveys masks a major distributional shift away from the uplands (North East Scotland Raptor Study Group 2015, Wilson et al. 2018) and towards lowland regions and the coast; Peregrine pairs in England have increased fivefold since 1981 and now, for the first time, outnumber those in Scotland (Wilson et al. 2018). Illegal persecution continues to limit numbers in the uplands, and food supply may also be a limiting factor in some areas; however persecution in lowland areas decreased during the 20th century, allowing numbers to benefit from the ban on organochlorine agrochemicals and from increased use of human structures as nest sites (Wilson et al. 2018).

Nest record information for the UK as a whole shows a significant rise in the number of fledglings per breeding attempt. This could at least partly reflect the distributional changes: urban Peregrines have a higher number of fledglings per breeding attempt than rural birds, possibly linked at least in part to higher prey availability (Kettel et al. 2018a, 2018b). In northern England, breeding productivity on grouse moors has been 50% lower than at nests in other habitats, indicating that illegal persecution on land managed for Red Grouse shooting remains an important pressure on the population (Amar et al. 2012).

Information about conservation actions

Although this species is increasing across many lowland areas of the UK, actions to reduce persecution are required to reverse recent declines in the uplands, where illegal persecution is believed to limit the population (see Causes of Change section).

Elsewhere, there are possible concerns about the risk of genetic introgression from escaped falcons following increases in the numbers of Peregrines and hybrid falcons in captivity (Fleming et al. 2011).

Publications (3)

Nesting dates of Moorland Birds in the English, Welsh and Scottish Uplands

Author:

Published: 2022

Rotational burning of vegetation is a common form of land management in UK upland habitats, and is restricted to the colder half of the year, with the time period during which burning may be carried out in upland areas varying between countries. In England and Scotland, this period runs from the 1st October to 15th April, but in the latter jurisdiction, permission can be granted to extend the burning season to 30th April. In Wales, this period runs from 1st October to 31st March. This report sets out timing of breeding information for upland birds in England, Scotland and Wales, to assess whether rotational burning poses a threat to populations of these species, and the extent to which any such threat varies in space and time.

17.02.22

BTO Research Reports

The breeding population of Peregrine Falcon Falco peregrinus in the United Kingdom, Isle of Man and Channel Islands in 2014

Author:

Published: 2018

The return of breeding Peregrines to former haunts, and the colonisation of urban sites such as industrial buildings and cathedrals, has not gone unnoticed by birdwatchers. It is only now, however, with the publication of the results from the latest national Peregrine survey, that we can put figures on the changing fortunes of this stunning bird of prey. The Peregrine breeding population in the UK and Isle of Man has been surveyed at intervals of 10 years since 1961/62. The first four surveys documented the recovery of the Peregrine population from the ‘crash’ of the 1960s (when numbers fell to less than half of the pre-war population) to the highest levels since recording began. The new national survey, carried out in 2014, sought to secure a new national population estimate and, in particular, to improve our knowledge of the species in lowland areas not traditionally regarded as being part of the Peregrine’s breeding range. The 2014 survey, co-ordinated by the BTO in partnership with many other raptor monitoring individuals and organisations, was made possible by the hard work of hundreds of volunteers. These fieldworkers surveyed a combination of known sites and randomly selected survey squares to secure evidence of occupation and breeding by Peregrines. The population estimate derived from the survey puts the UK Peregrine population at 1,769 breeding pairs, an increase of 22% on the previous survey (carried out in 2002). Most of the increase is accounted for by population growth in lowland England, with breeding Peregrines continuing to occupy new sites. Most of the inland breeding pairs utilise large cliffs, smaller crags or quarries, but an increasing proportion of pairs occupy man-made structures such as buildings, bridges, pylons and communication masks. Examination of the regional results reveals contrasting fortunes in Scotland, where there the population has declined overall. Worryingly, Peregrine populations are not doing well in the upland SPAs (Special Protection Areas) established to protect them, a pattern evident in both Scotland and northern England. Further losses of Peregrines from such areas might not pose a grave threat to the UK population, but could be important at a regional level. Possible factors associated with the poor performance of upland Peregrine populations may include prey abundance and availability, and illegal killing associated particularly with management of upland gamebirds for shooting, but also with recreational breeding and racing of domestic pigeons. Other factors may have affected Peregrine numbers at a local level; these include avoidance of Golden Eagles, oiling by Fulmars and exposure to a wide range of environmental pollutants. The findings of this survey provide an opportunity to investigate the effects of these and other issues, with complementary data sets – such as Bird Atlas 2007-11 or the RSPB’s data on upland land use – potentially of great value here.

06.03.18

Papers

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).