Golden Oriole

Introduction

Formerly a rare but regular breeder, the Golden Oriole is now a scarce visitor, most commonly reported in the spring, from April to the middle of June.

The last regular breeding took place in East Anglia, and the bird's disappearance has been linked to declining populations elsewhere.

Key Stats

Identification

Songs and Calls

Song:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Size

Population Change

The Golden Oriole was a scarce but regular breeding species in poplar plantations in East Anglia during the 1980s and 1990s but breeding numbers at the former core population at Lakenheath collapsed from 27 pairs in 1987 to four pairs in 2005 (Mason & Allsop 2009). This decline continued subsequently and the species is now effectively extinct as a breeding species in the UK. Occasional singing males continue to be reported to the Rare Breeding Birds Panel in most years, but the last confirmed breeding was in 2009 (Eaton et al. 2021).

Distribution

Golden Orioles have declined significantly and no longer breed regularly. During 2008–11 breeding was confirmed in two 10-km squares in the Suffolk fens and possible breeding in 27 squares. Many records away from the Fens probably refer to migrants; non-breeding birds were reported in a further 93 10-km squares in Britain and five in Ireland.

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

The change map highlights losses in the Fens and at other historical breeding sites.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

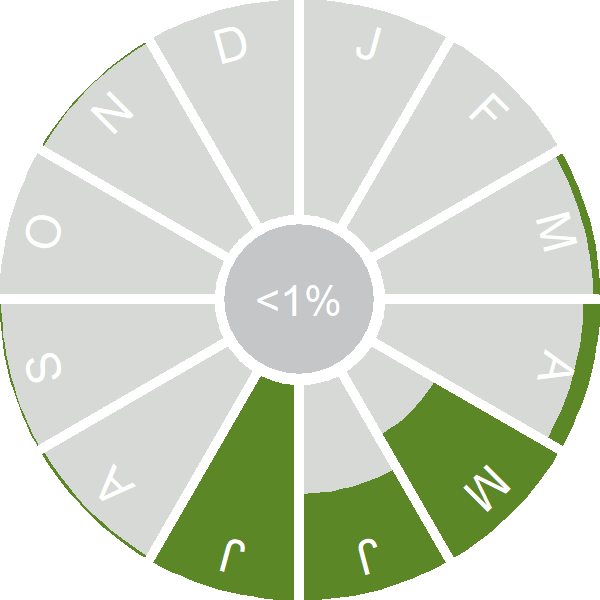

Seasonality

Golden Oriole is a former regular breeder and now mostly a spring overshoot migrant.

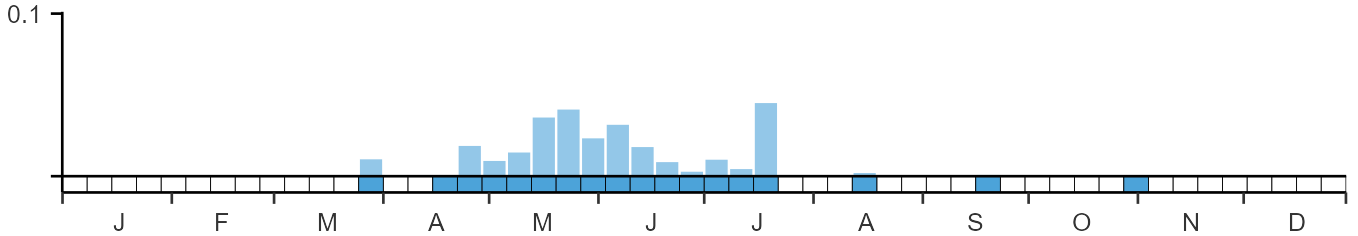

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Oriolidae

- Scientific name: Oriolus oriolus

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: OL

- BTO 5-letter code: GOLOR

- Euring code number: 15080

Alternate species names

- Catalan: oriol eurasiàtic

- Czech: žluva hajní

- Danish: Pirol

- Dutch: Wielewaal

- Estonian: peoleo

- Finnish: kuhankeittäjä

- French: Loriot d’Europe

- Gaelic: Buidheag-Eòrpach

- German: Pirol

- Hungarian: sárgarigó

- Icelandic: Laufglói

- Irish: Óiréal Órga

- Italian: Rigogolo

- Latvian: valodze

- Lithuanian: eurazine volunge

- Norwegian: Pirol

- Polish: wilga (zwyczajna)

- Portuguese: papa-figos

- Slovak: vlha obycajná

- Slovenian: kobilar

- Spanish: Oropéndola europea

- Swedish: sommargylling

- Welsh: Euryn

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

The drivers of the UK declines are unclear but the British population is linked to population trends in the Low Countries which are declining and this may have made the isolated UK population more vulnerable by reducing immigration. The declines in the Netherlands have been linked to habitat degradation but this is considered unlikely to have driven the UK extinction as sufficient suitable habitat was still available (Mason & Allsop 2009).

Publications (2)

Spatial variation in spring arrival patterns of Afro-Palearctic bird migration across Europe

Author:

Published: 2024

The timing of migrant birds’ arrival on the breeding grounds, or spring arrival, can affect their survival and breeding success. The optimal time for spring arrival involves trade-offs between various factors, including the availability of food and suitable breeding habitat, and the risks of severe weather. Due to climate change, the timing of spring emergence has advanced for many plants and insects which affects the timing of maximum food availability for migratory birds in turn. The degree to which different bird species can adapt to this varies. Understanding the factors that influence spring arrival in different species can help us to predict how they may respond to future changes in climate. This study looked at the variation across space in spring arrival time to Europe for 30 species of birds which winter in Africa. It used citizen science data from EuroBirdPortal, which collates casual birdwatching observations from 31 different European countries, including those submitted via BirdTrack. Using these data, the start, end and duration of spring migration was calculated at a 400 km resolution. The research identified patterns in arrival timing between groups of species, and tested whether these were linked to species traits: foraging strategy, weight, wintering location and length of breeding season. Lastly, it investigated how arrival timing was linked to temperature. The results showed that it takes 1.6 days on average for the leading migratory front to move northwards by 100 km (range: 0.6–2.5 days). The birds’ movements broadly tracked vegetation emergence in spring. Arrival timing could be split into two major groupings; species that arrived earlier and least synchronously, in colder temperatures and progressed slowly northward, and species that arrived later, most synchronously and in warmer temperatures, and advanced quickly through Europe. The slow progress of the early-arriving species suggests that temperature limits their northward advance. This group included aerial Insectivores (e.g. Swallow and Swift) and species that winter north of the Sahel (e.g. Chiffchaff and Blackcap). For the late-arriving species, which included species wintering further south, and heavier species (e.g. Red-backed shrike and Golden Oriole), they may need to wait until the wet season in Africa progresses enough for food to be available to them south of the Sahara before they can make the desert crossing. The research demonstrates that thanks to advances in citizen science, it is now possible to study arrival timing at a relatively fine scale across continents for a wide range of species, enabling a much fuller understanding of year-round variation between and within species, the associated trade-offs, and the pressures that species face. This knowledge can help mitigate threats to migrant species. For example, the dates of the start of spring migration could by used by each European country to inform hunting legislation. The approaches used in this work could be applied to other taxa where data are sufficient.

02.05.24

Papers

The risk of extinction for birds in Great Britain

Author:

Published: 2017

The UK has lost seven species of breeding birds in the last 200 years. Conservation efforts to prevent this from happening to other species, both in the UK and around the world, are guided by species’ priorities lists, which are often informed by data on range, population size and the degree of decline or increase in numbers. These are the sorts of data that BTO collects through its core surveys. For most taxonomic groups the priority list is provided by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) – the IUCN Red List comprises roughly 12,000 species worldwide and their conservation status. However, for birds in the UK, most policy makers refer to the Birds of Conservation Concern (BoCC) list, updated every six years (most recently in 2015). A new study funded by the RSPB and Natural England in cooperation with BTO, WWT, JNCC, and Game & Wildlife Trust has carried out the first IUCN assessment for birds in Great Britain. The study applied the IUCN criteria to existing bird population data obtained from datasets like the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey (BBS). The criteria take into account various factors, most notably any reduction in the size (both in abundance and range) of populations, loss of habitats key to the species, small or vulnerable population sizes, and extinction risk. Alongside this, the criteria look to see if there is a “rescue” effect – such as immigration from neighbouring populations that might boost the population’s numbers, reducing the risk of extinction. The species are then categorised into one of the threat levels below. The results of the new study show that a concerning 43% of regularly occurring species in Great Britain are classed as Threatened, with another 10% classified as Near Threatened. Twenty-three breeding or non-breeding populations of birds were classed as Critically Endangered, including Fieldfare and Golden Oriole (both possibly extinct as breeders), Whimbrel, Turtle Dove, Arctic Skua and Kittiwake, as well as non-breeding populations of Bewick’s Swan, White-fronted Goose and Smew., Over the past 200 years, seven species have gone extinct as breeders in Britain, including Serin, Temminck’s Stint and Wryneck in the past 25 years. The total percentage of threatened birds in Great Britain (43%) is high compared to that seen elsewhere in Europe (13%). Reasons for this are not entirely clear, although it may be that Britain’s island status has something to do with this, as there are fewer neighbouring “rescue” populations. Although the results from the IUCN assessment and BoCC assessment largely overlap, the IUCN assessment raises the level of concern for species such as Red-Breasted Merganser, Great Crested Grebe, Moorhen, Red-Billed Chough (all classed as Vulnerable), and Greenfinch (Endangered). These species might thus warrant closer monitoring in the near future. In contrast, the BoCC assessment identifies a number of species of concern whose declines have been more gradual but over long time periods (e.g. Skylark and House Sparrow). The authors emphasise that this assessment is not a replacement of the BoCC report, but rather that the two reports complement each other. With this new wealth of knowledge, there will hopefully be even more support for those species that need it most.

01.09.17

Papers

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).