Blue Tit

Introduction

This is a colourful little bird, and a familiar garden favourite. It is also common in woodland, hedgerows, parks and gardens.

Blue Tits have distinctive blue-green and yellow plumage and a blue cap. They regularly visit garden feeders and use nest boxes. Sexes are similar but, on average, males have slightly brighter colours than females.

The Blue Tit is a common resident breeder, widespread everywhere in Britain & Ireland except the Northern Isles and parts of the Hebrides. The UK population trend is stable, with some fluctuations.

Blue Tits often form mixed flocks with other tit species, especially in winter. In natural settings, they nest in tree holes and an average of of eight to 10 eggs once, sometimes twice, a year.

You can also read more about the Blue Tit's life during breeding season on our Blue Tit diary.

- Our Trends Explorer gives you the latest insight into how this species' population is changing.

Key Stats

Identification

ID Videos

This section features BTO training videos headlining this species, or featuring it as a potential confusion species.

GBW: Blue Tit and Great Tit

#BirdSongBasics: Blue Tit and Great Tit

Songs and Calls

Song:

Call:

Alarm call:

Begging call:

Status and Trends

Conservation Status

Population Change

Blue Tit populations have increased in abundance, with brief pauses in the long-term upward trend until around 2008, since when there has been a shallow decline. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that there were minor decreases over that period in parts of England and Northern Ireland and that increase occurred mainly in northwestern, upland parts of the UK range. There has been an increase across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Distribution

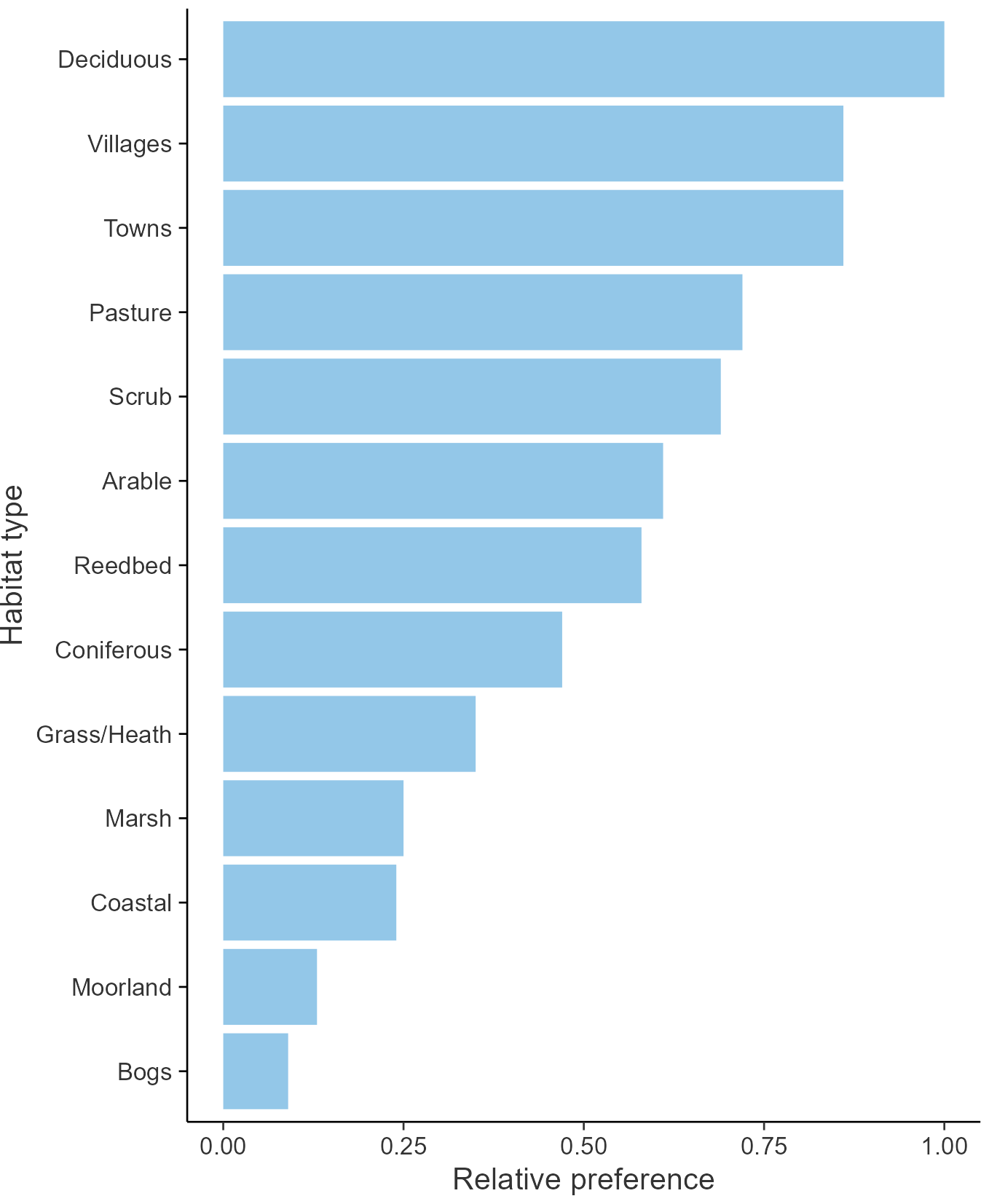

Blue Tits are widespread breeding and wintering species throughout Britain and Ireland, absent only from the highest ground in Scotland, the Northern Isles, most of the Outer Hebrides and a few Inner Hebridean islands. They are chiefly inhabitatnts of broad-leaved woodland, though abundant in a wide range of other woodland, garden and scrub habitats. Densities are low throughout Ireland, in upland areas of Britain and in other landscapes with few woodlands such as the Fens of East Anglia. The highest densities occur in central and southeast England and lower-lying areas of Wales.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

2007/08–10/11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

European Distribution Map

Distribution Change

Distribution changes in both seasons are minor, involving a few gains in marginal coastal and upland areas in Scotland and Ireland.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

from 1981–84 to 2007–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

from 1968–72 to 2008–11

or view it on Bird Atlas Mapstore.

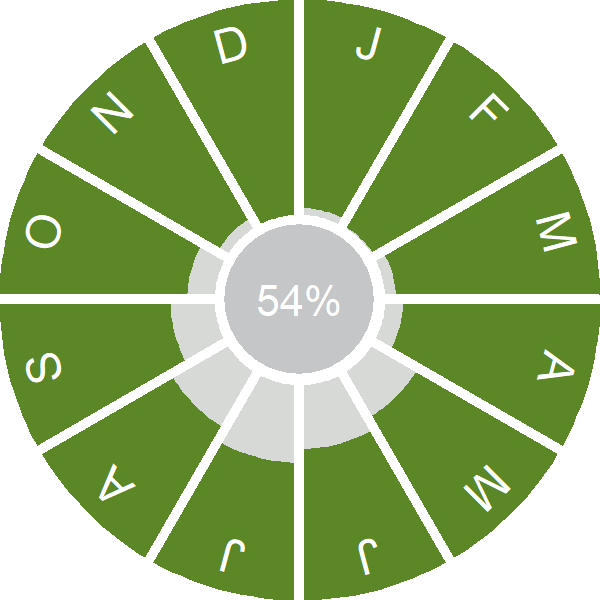

Seasonality

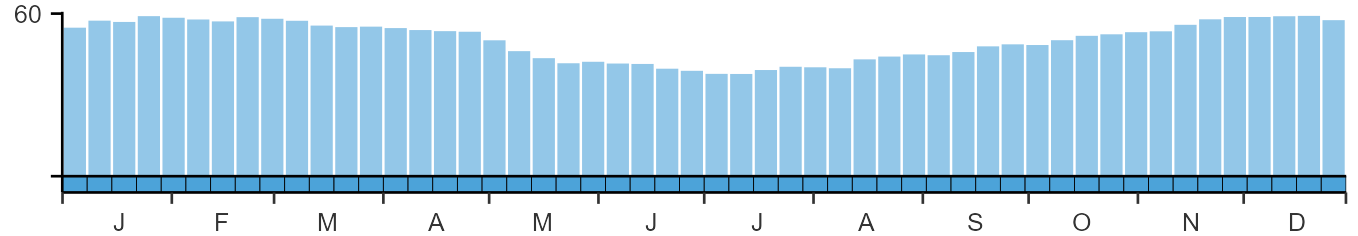

Blue Tit is recorded throughout the year on up to 60% of complete lists.

Weekly pattern of occurrence

The graph shows when the species is present in the UK, with taller bars indicating a higher likelihood of encountering the species in appropriate regions and habitats.

Habitats

Breeding season habitats

Relative frequency by habitat

The graph shows the habitats occupied in the breeding season, with the most utilised habitats shown at the top. Bars of similar size indicate the species is equally likely to be recorded in those habitats.

Movement

Britain & Ireland movement

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Dots show the foreign destinations of birds ringed in Britain & Ireland, and the origins of birds ringed overseas that were subsequently recaptured, resighted or found dead in Britain & Ireland. Dot colours indicate the time of year that the species was present at the location.

- Winter (Nov-Feb)

- Spring (Mar-Apr)

- Summer (May-Jul)

- Autumn (Aug-Oct)

European movements

EuroBirdPortal uses birdwatcher's records, such as those logged in BirdTrack to map the flows of birds as they arrive and depart Europe. See maps for this species here.

The Eurasian-African Migration Atlas shows movements of individual birds ringed or recovered in Europe. See maps for this species here.

Biology

Productivity and Nesting

Nesting timing

Egg measurements

Clutch Size

Incubation

Fledging

Survival and Longevity

Survival is shown as the proportion of birds surviving from one year to the next and is derived from bird ringing data. It can also be used to estimate how long birds typically live.

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report.

Lifespan

Survival of adults

Survival of juveniles

Biometrics

Wing length and body weights are from live birds (source).

Wing length

Body weight

Ring Size

Classification, names and codes

Classification and Codes

- Order: Passeriformes

- Family: Paridae

- Scientific name: Cyanistes caeruleus

- Authority: Linnaeus, 1758

- BTO 2-letter code: BT

- BTO 5-letter code: BLUTI

- Euring code number: 14620

Alternate species names

- Catalan: mallerenga blava eurasiàtica

- Czech: sýkora modrinka

- Danish: Blåmejse

- Dutch: Pimpelmees

- Estonian: sinitihane

- Finnish: sinitiainen

- French: Mésange bleue

- Gaelic: Cailleachag-ghorm

- German: Blaumeise

- Hungarian: kék cinege

- Icelandic: Blámeisa

- Irish: Meantán Gorm

- Italian: Cinciarella

- Latvian: zilzilite

- Lithuanian: melynoji zyle

- Norwegian: Blåmeis

- Polish: modraszka (zwyczajna)

- Portuguese: chapim-azul

- Slovak: sýkorka belasá

- Slovenian: plavcek

- Spanish: Herrerillo común

- Swedish: blåmes

- Welsh: Titw Tomos Las

- English folkname(s): Tom Tit

Research

Causes of Change and Solutions

Causes of change

Demographic trends in breeding parameters do not suggest that increases in this species are due to improvements in breeding performance. Evidence for ecological drivers of the population increase is limited but increased provisioning in gardens and milder winters may have played a role.

Further information on causes of change

Causes of change are likely to be similar to those for Great Tit (Robinson et al. 2014). A new strain of avian pox, first recorded in 2006, affects Blue Tits less frequently than Great Tits, and is unlikely to be behind the recent downturn which has occurred across the UK including regions where the disease is yet to be recorded (Lawson et al. 2018). Food provision in gardens during winter (Plummer et al. 2019) and availability of nest boxes, which may reduce egg and nestling predation, have both increased and may have contributed to the long-term rise in population. There have been no clear changes in fledglings per breeding attempt or in survival, however, to accompany the population increase.

Interspecific competition with Great Tits and intraspecific competition may also drive population changes in Blue Tits (Gamelon et al. 2019). As both species have increased in abundance over the long-term, density-dependent effects could thus have had a greater effect on Blue Tit which might explain the shallower long-term increase compared to Great Tit. The alert prompted from CES productivity measures may be caused by more frequent wet weather in June, as downpours can affect both tit species if they occur at the wrong time during the breeding cycle; however this is speculative and further analyses would be needed to confirm it.

Information about conservation actions

The population of this common and widespread species has increased since the 1970s with minor fluctuations, hence it is not a species of concern and no conservation actions are currently required. However, it has experienced a shallow decline over the last ten years and therefore ongoing monitoring would be prudent.

Ongoing provision of garden bird food is likely to continue to benefit the Blue Tit. However, the effects are not always entirely positive and feeders may contribute to the spread of avian pox, so those providing food should ensure they follow good hygiene practices. The provision of nest boxes, both in gardens and elsewhere, is also likely to continue to benefit this species.

Publications (9)

Declines in invertebrates and birds – could they be linked by climate change?

Author:

Published: 2023

The long-term declines evident in many bird and invertebrate species have their origins within a suite of potential drivers, one of which is climate change. As well as impacting bird species directly, could climate change be increasingly hitting bird populations through its impacts on their invertebrate prey?

09.01.23

Papers

The phenology and clutch size of UK Blue Tits does not differ with woodland composition

Author:

Published: 2023

17.06.23

Papers

Temporal avoidance as a means of reducing competition between sympatric species

Author:

Published: 2023

Human activities modify the availability of natural resources for other species, including birds, and may alter the relationships between them. The provision of supplementary food at garden feeding stations, for example, might favour some species over others and change the competitive balance between them. This paper investigates the behavioural responses to competition of the Marsh Tit, a species that is subordinate to both the Blue Tit and the Great Tit.

24.05.23

Papers

Evidence that rural wintering populations supplement suburban breeding populations

Author:

Published: 2022

Urban areas can and do hold significant populations of birds, but we know surprisingly little about how these populations are connected with those present within the wider countryside. It has been suggested that the populations using these different habitats may be linked through seasonal movements, with individuals breeding in rural areas moving into urban sites during the winter months to exploit the supplementary food provided at garden feeding stations. However, little work has been done to test this hypothesis.

24.11.22

Papers Bird Study

The effects of a decade of agri-environment intervention in a lowland farm landscape on population trends of birds and butterflies

Author:

Published: 2022

Food production and wildlife conservation are often thought of as incompatible goals, and it is rare that conservation studies consider both economics and long-term changes in ecology. However, a decade-long study at a commercial arable farm in Buckinghamshire has found that agri-environment schemes significantly increased local bird and butterfly populations without damaging food production, offering hope for the UK’s farmland birds and butterflies.

01.08.22

Papers

Effects of winter food provisioning on the phenotypes of breeding blue tits

Author:

Published: 2018

Our understanding of the impact of feeding wild birds is far from complete, but we are beginning to unravel the effects of providing foods at garden feeding stations. An important area of research has been to examine how supplementary foods shape populations through its impacts in individuals. Feeding wild birds is a popular pastime and many of us provide seed and other foods to help our feathered friends. But what impact does all this food have? It is a huge resource and one that can increase overwinter survival and bring forward the timing of breeding, but we also know that the feeding of wild birds has been linked to the transmission of disease. Research by Kate Plummer and colleagues provides new insight into one particular aspect of food provision – how it shapes bird populations. Kate’s research has examined the extent to which the provision of supplementary food during the winter months influences the physiological condition of individuals and populations the following breeding season. By using woodland populations of Blue Tits, Kate and fellow researchers have been able to compare the effects of providing fat, and fat plus vitamin E (an antioxidant), against a control population of unfed birds. The feeding carried out during the winter months ended at least a month before the tits began egg-laying. Provisioning with fat and vitamin E was found to alter the composition of Blue Tit populations, such that they included birds that had been in significantly poorer condition prior to feeding. Because those individuals were found to have lower levels of carotenoids in their breast feathers than unfed birds, Kate was able to conclude that supplementing with vitamin E and fat in winter had altered the survival and recruitment prospects of these lower quality individuals; lower levels of carotenoids are indicative of poorer physiological condition. However, provisioning with fat alone was found to have a detrimental impact on breeding birds. It appears that the provision of supplementary foods during the winter months can alter both the structure of the breeding population the following season, and the condition of individual breeding birds. Such effects may have consequences even longer term; through this work, for example, it was found that individuals with higher blood plasma concentrations of malondialdehyde (which is indicative of oxidative damage) produced offspring that were structurally smaller and which suffered from reduced fledging success. The importance of antioxidants, like vitamin E, can also be seen from Kate Plummer’s earlier work on yolk mass. While Plummer et al. (2013) found that winter provisioning with fat subsequently impaired an individual’s ability to acquire, assimilate and/or mobilise key resources for yolk formation, this was not the case where vitamin E was also included in the food presented. A high fat diet, such as that potentially obtained from the food provided at garden feeding stations, may well increase the requirement for antioxidants in order to combat the greater levels of oxidative damage associated with a diet rich in fats. Clearly, there is still much to learn about how the provision of supplementary food affects wild birds and their populations.

24.04.18

Papers

Tritrophic phenological match-mismatch in space and time

Author:

Published: Spring 2018

The increasing temperatures associated with a changing climate may disrupt ecological systems, including by affecting the timing of key events. If events within different trophic levels are affected in different ways then this can lead to what is known as phenological mismatch. But what is the evidence for trophic mismatch, and are there spatial or temporal patterns within the UK that might point to mismatch as a driver of regional declines in key insect-eating birds? A changing climate is leading to changes in the timing of key ecological events, including the timing of bud burst, the spring peak in leaf-eating caterpillar biomass and the timing of egg-laying in many bird species. If the timings of these different events shift at different rates then there is a danger that they may get out of synch with one another, something that is referred to as phenological mismatch. This may be a particular problem for birds like Blue Tit, Great Tit and Pied Flycatcher, which time their breeding attempts to exploit the spring peak in caterpillar abundance. Much of the recent work on mismatch and its impacts on the fitness and population trends of caterpillar-eating birds has looked at changes over time. However, it is also possible for mismatch to vary in space if species respond differently in different areas, perhaps because of local adaptation to geographic variation in the cues that they use. This paper looks at mismatch in both space and time, using information from three trophic levels, namely trees, caterpillars and caterpillar-eating birds. While information on bud burst came from 10,000 observations of oak first leafing for the period 1998-2016, that for caterpillar biomass was inferred from frass traps set beneath oak trees at sites across the UK for the period 2008-2016. Bird phenology data came from the ‘first egg date’ values calculated from 85,000 nest records of Blue Tit, Great Tit and Pied Flycatcher. The focus of the work was on the relationship between the phenologies of these interacting species; where timing changes more in one species than the other, this is indicative of spatial or temporal variation in the magnitude of mismatch. The results reveal that, for the average latitude (52.63°N) and year, there is a 27.6 day interval between the timing of oak first leaf and peak caterpillar biomass. With increasing latitude, the delay in oak leafing is significantly steeper than that of the caterpillar peak. At 56°N the predicted interval between these two trophic levels drops to 22 days. In the average year and at the average latitude, the first egg dates of Blue Tits and Great Tits were roughly a month earlier than peak caterpillar biomass, meaning that peak demand for hungry chicks occurred soon after the peak in resource availability. Interestingly, peak demand in Pied Flycatchers occurred nearly two weeks later than peak caterpillar availability, suggesting a substantial trophic mismatch between demand and availability for this species within the UK. However, it is worth noting that Pied Flycatchers provision their nestlings with fewer caterpillars and more winged invertebrates compared to the tit species studied, so they may be less dependent on the caterpillar peaks. The work also revealed that the timing of first egg date between years varied by less than the variation seen in timing of the caterpillar resource peak, which gave rise to year-to-year variation in the degree of mismatch. For every 10 day advance in the caterpillar peak, the corresponding advance in the three bird species is 5.0 days (Blue Tit), 5.3 days (Great Tit) and 3.4 days (Pied Flycatcher). In late springs, peak demand from the tits is expected to coincide with the peak resource availability, with flycatcher demand occurring shortly after. In early springs, the peak demand of nestlings of all three species falls substantially later than the peak, leaving the three mismatched. Warmer conditions also shortened the duration of caterpillar peaks. One of the key findings of the work is that in the average year there is little latitudinal variation in the degree of caterpillar-bird mismatch. This means that more negative declines in population trends of certain insectivorous birds in the southern UK, driven by productivity, are unlikely to have been driven by greater mismatch in the south than the north. The lack of evidence for latitudinal variation in mismatch between these bird species and their caterpillar prey suggests that mismatch is unlikely to be the driver of the spatially varying population trends found in these and related species within the UK.

23.04.18

Papers

A method to evaluate the combined effect of tree species composition and woodland structure on indicator birds

Author:

Published: 2015

Providing quantitative management guidelines is essential for an effective conservation of forest-dependent animal communities. Traditional forest practices at the stand scale simultaneously alter both physical and floristic features with a negative effect on ecosystem processes. Thus, we tested and proposed a method to define forestry prescriptions taking into account the combined effect of woodland structure and tree species composition on the presence of four bird indicator species (Marsh Tit Poecile palustris, European Nuthatch Sitta europaea, Short-toed Tree-creeper Certhya brachydactyla and Blue Tit Cyanistes caeruleus). The study was carried out in Lombardy (Northern Italy), from 2002 to 2005. By using a stratified cluster sampling design, we recorded Basal Area, one hundred tree trunk diameters at breast height (DBH) and tree species in 160 sampling plots, grouped in 23 sampling areas. In each plot we also performed a bird survey using the point count method. We analyzed data using Multimodel Inference and Model Averaging on Generalized Linear Mixed Models, with species presence/absence as the response variable, sampling area as a random factor and forest covariates as fixed factors. In order to test our method, we compared it with other two traditional approaches, which consider structural and tree floristic variables separately. Model comparison showed that our method performed better than traditional ones, in both the evaluation and validation processes. Based on our main results, in deciduous mixed forest where the exploitation demand is limited, we recommend maintaining at least 65 trees/ha with DBH>45cm. In particular, we advise keeping 70 trees/ha with DBH>50cm in chestnut forests and 300 trees/ha with DBH 20–30cm in oak forests. Conversely, in more exploited oak forests, we advise maintaining at least 670 trees/ha with DBH 15–30cm in chestnut forests and 100 trees/ha with DBH 10–15cm. Providing quantitative management guidelines is essential for an effective conservation of forest-dependent animal communities. Traditional forest practices at the stand scale simultaneously alter both physical and floristic features with a negative effect on ecosystem processes. Thus, we tested and proposed a method to define forestry prescriptions taking into account the combined effect of woodland structure and tree species composition on the presence of four bird indicator species (Marsh Tit Poecile palustris, European Nuthatch Sitta europaea, Short-toed Tree-creeper Certhya brachydactyla and Blue Tit Cyanistes caeruleus). The study was carried out in Lombardy (Northern Italy), from 2002 to 2005. By using a stratified cluster sampling design, we recorded Basal Area, one hundred tree trunk diameters at breast height (DBH) and tree species in 160 sampling plots, grouped in 23 sampling areas. In each plot we also performed a bird survey using the point count method. We analyzed data using Multimodel Inference and Model Averaging on Generalized Linear Mixed Models, with species presence/absence as the response variable, sampling area as a random factor and forest covariates as fixed factors. In order to test our method, we compared it with other two traditional approaches, which consider structural and tree floristic variables separately. Model comparison showed that our method performed better than traditional ones, in both the evaluation and validation processes. Based on our main results, in deciduous mixed forest where the exploitation demand is limited, we recommend maintaining at least 65 trees/ha with DBH>45cm. In particular, we advise keeping 70 trees/ha with DBH>50cm in chestnut forests and 300 trees/ha with DBH 20–30cm in oak forests. Conversely, in more exploited oak forests, we advise maintaining at least 670 trees/ha with DBH 15–30cm in chestnut forests and 100 trees/ha with DBH 10–15cm.

01.04.15

Papers

Passerines may be sufficiently plastic to track temperature-mediated shifts in optimum lay date

Author:

Published: 2016

19.05.16

Papers

More Evidence

More evidence from Conservation Evidence.com

Partners

Citing BirdFacts

If you wish to cite particular content in this page (e.g. a specific value) it is best to use the original sources as linked in the page. For a more general citation of the whole page please use: BTO (20XX) BirdFacts Species: profiles of birds occurring in the United Kingdom. BTO, Thetford (www.bto.org/birdfacts, accessed on xx/xx/xxxx).