Read reviews of the books we hold in the Chris Mead Library, written by our in-house experts. A selection of book reviews also features in our members’ magazine, BTO News.

Featured review

All the Birds of the World

Lynx have had a long-term project to produce an exhaustive guide to the birds of the world. It started out with the 17 volumes of the Handbook of the Birds of the World (1992–2013) which has family and species accounts for all birds. This was followed by the two volumes of the Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World (2014–2016). They have now published the third and final stage of this avian odyssey with this current book.

Search settings

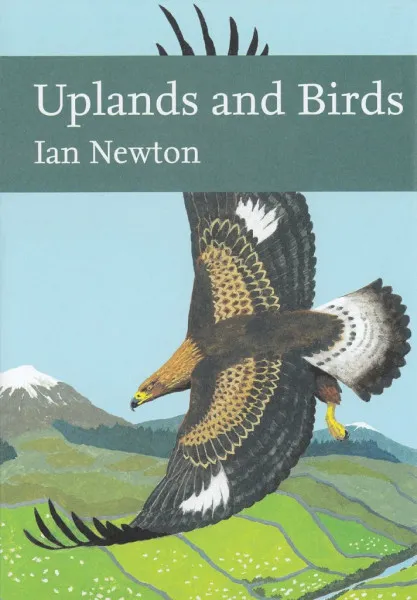

Uplands and Birds

Author: Ian Newton

Publisher: William Collins, London

Published: 2020

Once again, Ian Newton has produced another brilliant book. As always, it is packed with facts and ideas presented in a clear and easy style that both grips one’s interest and deepens one’s understanding. The uplands are often thought of as more natural or unspoilt than the lowland landscapes of Britain, their state determined largely by their topography, geology and climate. But Newton shows how today’s upland landscapes have been created by human activities over thousands of years. He deals with the management, ecology and birds of grouse moors, deer forests, hill farms, native woodlands and conifer plantations and with the conflicting aims and views that different people have about their management. As in the lowlands, changing land-use has much affected the distribution and numbers of birds, sometimes by deliberate intent (such as the persecution of birds of prey) but often unintended (such as the loss of eagle territories following blanket afforestation). Newton has taken as his task not the promotion of particular solutions to the contentious arguments about upland land-use but the full presentation of the facts that need to be considered if we are to arrive at solutions that satisfy our conservation objectives and society’s needs. As an example of his approach, we may take the management of grouse moors, the hottest topic in upland land-use, at least for birdwatchers. Provision of grouse-shooting is competitive, for the value of the land (about the only financial benefit that the moor delivers to its owners) depends on the numbers of grouse available to be shot. To try to produce large numbers, managers burn vegetation, drain peat, control predators (both legally and illegally), put out grit medicated with antihelminthic drugs and control ticks using acaricides on sheep and by culling hosts such as Mountain Hares. Unlike farmers and foresters, who are greatly supported by the tax-payer, the shooters of grouse (and deer) fund their own expensive hobbies. And, although their activities impose costs on the wider community (such as the treatment of peat-laden water originating from the drainage of moors and the damage to trees by deer), they bring employment to economically deprived communities in places where other land-uses may not be feasible. Newton concludes that “Management for Red Grouse arguably causes less damage than any other form of upland land use as currently practised, apart from rewilding.” But this does not present us with a simple solution to upland management for “Raptor killing is the main issue that divide grouse-moor managers and conservation organisations, which otherwise have much in common.” Although the entrenched positions of the two sides make it difficult, “Only dialogue and compromise on both sides is likely to lessen this conflict.” Any birdwatcher will enjoy this book and benefit from reading it. No hunter, farmer, forester, conservationist, politician or public servant should pontificate on how the uplands should be managed without carefully studying what Newton has to say…

The Biology of Moult in Birds

Author: Lukas Jenni & Raffael Winkler

Publisher: Helm, London

Published: 2020

Moult is a fascinating basic life history event in birds which, despite its major impact on their life cycle, is relatively poorly understood and even neglected. This is a companion to the excellent Moult and Ageing of European Passerines (secodnd edition, 2020) by the same authors, previously reviewed in BTO News 335. It started life as a revision of the short summary in the introductory chapters of the Moult and Ageing of European Passerines (first edition, 1994) for the second edition, before being expanded into a book in its own right, as arguably the first general review on moult in birds covering the biology, physiology and ecology of moult. The book itself is divided up into five main chapters covering: 1) the functions of moult, 2) plumage maintenance and why it needs renewal, 3) the actual process of moulting, 4) the effects of environmental conditions during moult on plumage quality and its consequences, and 5) how moult fits into the annual cycle with regards to moult strategies. Each chapter can more or less stand on its own, which does result in some repetition due to the same topics and findings being relevant to more than one area, but it does also avoid the need to read it from cover to cover if you are primarily interested in only part of the work. To aid this, each chapter is subdivided into sections and subsections with helpful short summaries at the end of many of the subsections, and a longer summary and concluding remarks at the end of each section to summarise current knowledge and suggest further research ideas, allowing readers to get the gist of sections quickly. While perhaps not the lightest of reading at about 240 pages plus many pages of references, the more complex topics are explained and summarised well and anybody with an interest in bird moult, such as bird ringers, should find it easy to get into. It’s not a guidebook so don’t expect species accounts, but a wide range of species is mentioned as the authors draw from moult literature across the bird families, highlighting both relatively common moult strategies and traits along with the more unusual, including at times considering differences in moult of closely related species and even subspecies. As the authors, their work (and perhaps most of this book’s likely readers) are based in Europe, there is perhaps an understandable slight bias towards European breeding and moulting species so a more in-depth exploration of the complex moults of North American passerines or topical moulting species including our own migrants could have being interesting, but this a minor quibble and they are still covered. The figures, both diagrammatic and photographs, are excellent and informative throughout, including many example photos of bird wings with in-depth explanatory captions and sometimes labelling in similar vein to their books on European passerine,s although also including non-passerines. All in all, if you want a deep understanding of bird moult biology and processes this book is easily the most in-depth book in existence on this topic while remaining accessible. Although the primary readership is likely to be bird ringers and academics, this book is of potential interest to all ornithologists seeking a greater understanding of bird moult and appearance.

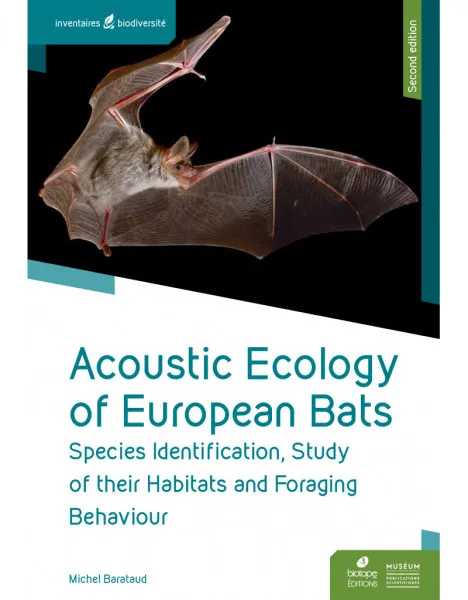

Acoustic Ecology of European Bats: Species Identification, Study of their Habitats and Foraging Behaviour

Author: Michel Barataud (author), Yves Tupinier, Herman J.G.A. Limpens (contributors) & Anya Cockle-Betian (translator)

Publisher: BIOTOPE, Paris

Published: 2020

With developments in bat detectors, particularly passive detectors which are left outside to automatically trigger and record any bats that fly past, there is the potential to provide representative acoustic monitoring of bat species distribution and activity as a measure of relative abundance. Whilst software for semi-automating the analysis of sound files is available and can save considerable time in helping to assign recordings to species as a first analyses, acoustic identification using these approaches is not perfect for many species. For this reason, having a clear understanding of how bats calls vary and how far to push identification is essential. Acoustic Ecology of European Bats, which was first published in English in 2015, is the result of over 30 years of research by the author. My previous review of the first edition can be found here. In 2020, a second edition was produced, which I was keen to review again. As with the first edition, the introduction summarizes the basis of biological sonar and gives an overview of the technologies used to convert ultrasound into audible frequencies. The identification criteria for 34 European bat species (and covered all British bats) are given in detail, with an entire chapter devoted to the methodology of the acoustic study of their foraging habitats. Acoustic Ecology of European Bats focuses on the concept of acoustic ecology, illustrated with many examples. This concept explains how the acoustic behaviour of a bat sheds light on its flight environment, its activity, and diet, contributing in all cases to improving the reliability of species identification. For this edition, rather than including a DVD, a downloadable folder of sound files is available online here, which I have found extremely useful. It also includes figures in .xls format, comparing important call parameters for helping in the identification of all bat species. Acoustic Ecology of European Bats contains a wealth of information indispensable to amateur naturalists and professionals involved in the management of protected areas or in environmental impact studies. With the second edition of this book published five years after the first, this remains the most extensive reference to date on the acoustic identification of European bats. For readers who already have the first edition of this book, changes from the first to second edition are small. The main change being an increase in the total number of sound recordings underlying the analyses in the book from 1,058 to 1,153, but there is little new interpretation. For owners of the first edition, there are likely to be too few changes to warrant purchasing the second edition, but those who don’t, and are interested in the sound identification of bats, this is essential reading.

Avifaunas, Atlases & Authors: a Personal View of Local Ornithology in the United Kingdom, from the Earliest Times to 2019

Author: David Ballance

Publisher: Calluna Books, Wareham

Published: 2020

As the title of this book suggests, it is a meta-book; a book about other books. Its main purpose is to inform the reader about works that deal, in various ways, with the element of place in ornithology. These can largely be separated into books describing where different birds occur within a country or region (atlases), and those describing the occurrence and status of birds in one or more localities (avifaunas). It is a follow-up to a previous book (and three large supplements expanding on it) by the same author called Birds in Counties, which was published in 2001. Birds in Counties extracted annotated bird species lists from all the main books, papers, articles and reports of relevance to each county in the UK. By contrast, this book does not aim to summarise the available information but, rather, grants readers an awareness of this vast literature, and better equips them to navigate within it. The book is divided into two parts, the first of which sets the scene by describing how bird-recording has evolved in Britain and Ireland. In doing so, the author also deals with works that have an over-arching significance, such as those deriving from the four British and Irish Atlas projects. The second, much larger section takes the reader county by county through publications whose perspective is more local. Over 100 pages in this section are taken up with bibliographies for each county; but Ballance takes the reader far beyond a list of the relevant authors, dates and titles. Each chapter gives some sense of the main bird-related interests within the county and the history of local ornithology there. In describing the relevant literature, he clearly conveys the significance of the main works with useful information about their scope and quality, as well as their relevance and availability both to historical scholars and modern-day readers. However, perhaps the main attraction of the book, from a non-academic perspective, is the author’s vivid portrayal of hundreds of ornithologists who have contributed to bird recording in one or more of these counties. A few of these people will likely be familiar to most readers; but the vast majority will not be. In providing us with glimpses into the lives and characters of these extraordinary people and their remarkable achievements, Ballance brings to life what might otherwise have been quite a dry recital of books, dates and places. This impressive tome will be an essential addition to most ornithological libraries. Its ring-bound 314 A4 pages give it a thesis-like appearance, but the breadth and depth of knowledge it contains far exceeds what can be accumulated during a few years of concentrated research. As well as enabling the author’s stated aim of producing the book for relatively little cost (thereby making it accessible to as wide a readership as possible), this format makes the book well suited to being used as a reference, which is its main purpose. This is not a book that is destined to be read from cover to cover by the majority of its owners. However, the wealth of interesting information it contains, and the quality of the writing with which this is conveyed, make it a highly enjoyable book to dip into. Such an encounter might serve as a quick history lesson on one’s own county, or take a more meandering path through the evolution of local ornithology. In either case, it will probably be more entertaining than you expect!

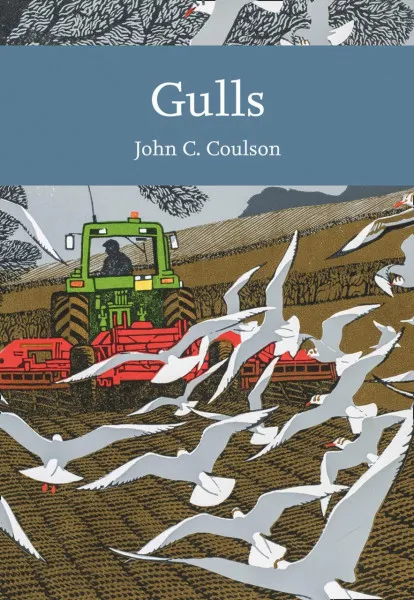

Gulls

Author: John C. Coulson

Publisher: William Collins, London

Published: 2019

Gulls is a weighty addition to the New Naturalist series, with almost 500 densely-worded pages (including appendices and indices). This is not entirely surprising, given the lengthy research career of the author, whose peer-reviewed publications on gulls span seven decades. But what of the information therein? Gulls focuses on species found in Britain and Ireland. There is an overview chapter, setting the scene in 42 pages, which is followed by nine chapters on particular species. These vary a lot in length and depth. The longest chapters are devoted to the Kittiwake and the Herring Gull, with 64 and 58 pages respectively. At the other extreme, the Yellow-legged Gull has six pages and the Little Gull eight. These discrepancies are partly connected to how common, widespread and well-studied each species is in Britain and Ireland, but are also driven by the amount of research the author has himself done on each species. There are extensive descriptions of the work carried out by Coulson himself and his students, which are very interesting to read from a historical perspective. However, I sometimes felt that the broader context was lost; although I came away feeling far better educated about the status of Herring Gulls on the Isle of May in the 1970s, for example, I would have liked to have seen these detailed accounts discussed in light of more recent work. A chapter on rare gulls follows the individual species accounts, which leads on to description of the methods used to study gulls, the author’s take on urban gulls and finally his views on conservation, management and exploitation of gulls. Coulson is scathing about most recent decisions assigning a particular conservation status to the various gull species discussed in the book, which is interesting given BTO’s role in the Birds of Conservation Concern Red List. He is also dismissive of the various gull control techniques often discussed in the media during the summer months, when urban gulls can make headlines for all the wrong reasons. The book could have done with a closer editorial eye. There are a number of small slips. For example, the JNCC is referred to as the Joint Nature Conservancy Council on more than one occasion, and the (human) population of Britain and Ireland in 2017 shrinks from 76 million on page 374 to 74 million on page 416. There are also mistakes in descriptions of gull studies, which I found less forgivable. For instance, Coulson states that a limitation of using GPS tags to track gulls’ movements is that birds need to be recaptured and the tag retrieved to access the data. While this is true for some types of tags, remote-download versions have been available and widely used in gull research (including in studies cited in the book’s bibliography) for a number of years. The quality of the photos is also lacking in some places. While certain images are excellent and suitably illustrate the points Coulson makes in the text, in others the birds are hard to see, the light is poor, and in a few instances, the species given in the image caption is incorrect. I also felt that the space taken up by line and bar charts, especially those describing historical studies, could have been better used with informative figures from more recent research. Coulson’s long-view is, however, very interesting and informative. It gives real insight into his work as a pioneer in this field of ornithology, such as his innovations with colour ringing, which revolutionised seabird research. His accounts of culling programmes on the Isle of May and Bowland are also thought provoking, especially in light of recent changes to the licensing of lethal control of large gulls in England. Overall, Gulls is an interesting addition to the bookshelf, especially if you are seeking historical information on these sometimes maligned and misunderstood species.

Birds of the UK Overseas Territories

Author: Roger Riddington(Editor) & Miranda Krestovnikoff(Foreword By)

Publisher: Poyser, London

Published: 2020

Readers of British Birds will most likely be familiar with much of the content of this new publication from Poyser, which brings together 13 papers published over the past 12 years, each describing the birds of the various far-flung remnants of Britain’s colonial history. Each of these papers now forms a chapter that gives a detailed introduction to the ornithological interest of the United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs). The addition of the paper on the British Virgin Islands, which has not yet been published in British Birds, completes the set, along with a new introductory chapter explaining the importance of the UKOTs for global biodiversity. Many of the older papers include postscript updates on particularly pressing or long-running conservation issues, and some also provide new advice on travelling to and submitting records within the territories. This book is a whistle-stop tour of some truly spectacular parts of the world, whipping from the arid slopes of Ascension Island to the frigid shores of South Georgia, to the tropical islands of the Caribbean and the white sandy beaches of Henderson Island in the Pacific Ocean. For the carbon-conscious birder this is a great summary of the birdlife of some places that you may be unlikely to visit, though for me it certainly invoked itchy-feet! Most of the UKOTs are islands or archipelagos, and so species endemism is high, meaning that each chapter has something new to offer, including those for UKOTs that are relatively close to one another such as Anguilla and Montserrat. As each territory is quite discreet (with the obvious exception of the vast British Antarctic Territory), at no point does the book become overwhelming with statistics and figures, providing population estimates in local and regional contexts. Given the length of time between authoring of each paper, there is no set layout for each chapter, but broadly they cover: a description of the breeding birds with special focus on endemics; an account of the migratory and vagrant birds that occur; habitats, climate and vegetation through time; a history of bird recording up to present, and; a run-through of past, current and expected conservation issues. The UKOTs hold a wealth of biodiversity, but a recurring theme throughout the chapters is that despite the many thousands of miles of ocean that separate the them, the threats posed by invasive species, human development pressure and climate change are shared by them all. As pointed out in the introduction, the strange constitutional situation UKOTs find themselves in means that they have limited access to international or UK conservation funds. Much of the vital conservation work to protect fragile environments, safeguard unique island endemics and conserve globally threatened species is carried out by passionate local ornithologists and conservationists, and a particular highlight of this book is how it showcases local conservation success stories, such as the remarkable recovery of the Cahow (Pterodroma cahow) in Bermuda. The individual chapters of this book are a good primer for visiting birders to each of the UKOTs, and provide helpful tips on spotting local specialties, where to visit and sometimes who to speak to. Given the disparate nature of the territories that the UK currently has responsibility for, the real value of this book is as a compilation of the immense diversity of life and environments that the UK has responsibility for beyond the shores of Britain. I feel this is a book that should be on the shelves of UK conservation policymakers as a reminder that some of the species and habitats we need to prioritise for conservation and research may not necessarily be right on our doorstep.

Rostherne Mere: Birds of Mere and Margin: One Hundred and Thirty Years of Observations

Author: Steve Barber, Bill Bellamy and Tom Wall; with Ray Scally (illus.)

Publisher: Tom Wall (privately published)

Published: 2019

This book is a nice local avifauna of the famous Rostherne Mere National Nature Reserve in north Cheshire. But if the word ‘avifauna’ makes readers think of their standard format – a dry catalogue of species, with interrogation of old records to see if they meet modern identification criteria – they will be in for a surprise; in my opinion, a pleasant one. The authors have adopted a charming style, enlivened by copious anecdotes and plenty of photographs and illustrations (by Ray Scally), making an eminently readable volume. One surprise is their loose adherence to taxonomic order, with some birds dealt with in groups according to habitat, the allotted amount of space varying greatly according to the amount of study that each has had. For instance, the chapter ‘a miscellany at the margins’ covers 19 species from Marsh Harrier and Osprey to Kingfisher and Starling. Of course this means an element of referring to the index to find out where a species occurs, but probably no more than needed in all bird-books to keep up with the frequent changes to the systematic list. The records cover 130 years, from 1886 to 2016, the site having inevitably had varying intensity of study during that time. Rostherne is fortunate that for the first half of the 1900s it benefited from the attention of two local ornithologists who had risen to national prominence through their writings (T.A. Coward and A.W. Boyd), and records from their network of correspondents. In the last half-century or so, events such as appointment of Nature Conservancy wardens, construction of an observatory building, donation of a monster telescope and a programme of ringing all encouraged observations so that birds have been recorded on most days. This book is a welcome overview of the birds of Rostherne Mere and will, I believe, be enjoyed by anyone, whether or not they have ever been there. Those interested in more than just the birds will learn much from the companion volume Rostherne Mere – Aspects of a Wetland Nature Reserve.

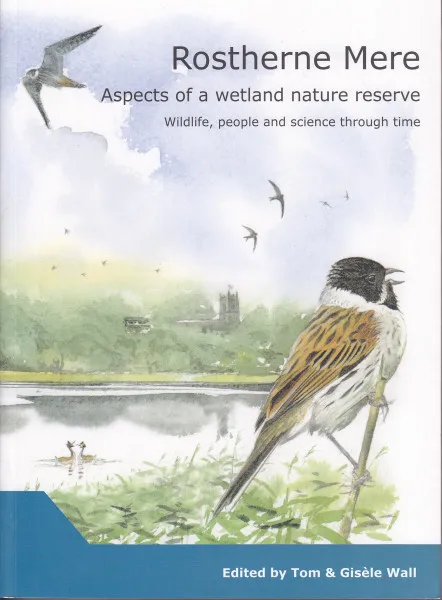

Rostherne Mere: Aspects of a Wetland Nature Reserve: Wildlife, Science and People Through Time

Author: Tom Wall and Gisèle Wall (eds.)

Publisher: Tom Wall (privately published)

Published: 2019

In 1912, the grandly-named Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves for Britain and the Empire, fore-runner of The Wildlife Trusts, started to compile a list of 284 potential reserves in the British Isles. Rostherne Mere was included, although the benevolent ownership by the Egerton family meant that there was not seen to be any urgency in securing its conservation by other organisations and the site, especially its birds, was well-recorded. But eventually its vulnerability was recognised – including as a picnic and bathing spot for Manchester residents! – and numerous behind-the-scenes negotiations in the 1950s, masterminded by Max Nicholson, Director-General of the newly-formed Nature Conservancy, led to Lord Egerton, with no heirs, bequeathing the Mere to the nation. So, Rostherne Mere became, in 1961, our 99th National Nature Reserve (NNR). This is an imperfect précis of half a century’s progress to NNR status, described in fascinating detail in the first part of this book, with interesting insights into the mixture of personal relations, politics and finance, with a focus on conservation helping to hold it all together. Physically, Rostherne is the most northerly and deepest of the Ice Age meres of the Cheshire-Shropshire Plain, reaching over 30 m, and the last to freeze over. It is thus not surprising that its main importance was seen as a wildfowl refuge. As an NNR, Nature Conservancy wardens undertook more surveys of flora and fauna themselves, as well as lots of management work, and went out to recruit numerous academic and other researchers into other aspects of the Mere’s natural history. Accounts of the management – especially grappling with water quality, eutrophication and pollution – and of research, mostly on fish, make up the rest of the book, some with chapters written by the lead researchers themselves. There is a little overlap with the Birds of Mere and Margin volume, with a summary chapter on the birds, including a long-running study of Reed Warblers, but they have a different focus and I doubt that any purchaser of both books would feel cheated by their repeated appearance. Tom Wall, as principal author, must be congratulated for his vision in conceiving, and the immense scholarship in producing this masterpiece, all written in an engaging style and including every imaginable document, map, graph and photograph. It is a joy to read, and also repays study and thought, with lessons to be learned even now.

Birds of the West Indies

Author: Herbert A. Raffaele, James W. Wiley, Orlando H. Garrido, Allan R. Keith & Janis Raffaele

Publisher: Helm, London

Published: 2020

Having observed last year when reviewing the excellent new Lynx Edicions Birds of the West Indies following a recent trip to the region, that all the available bird guides at that time appeared to be reprints of older books, it’s good to see one of those books has now been given a much needed update. For many years, the Helm Birds of the West Indies has been the go-to guide for the region, as a clear, straightforward, no nonsense book. This new slightly enlarged second edition takes the good basics of the prevision edition and improves on it while adding 60 more species (now covering >600 species) and importantly updating the conservation statuses and ranges of the region’s species. As you would expect in a new edition there is new artwork, both for the new species but also replacing much of the more old-fashioned artwork such as all the warbler and some of the flycatcher plates from the first edition with better images. The images are also better spread out with less species per plate on average, making the guide less cluttered and allowing the already well set out written species accounts to be expanded to make them more informative whilst remaining concise. Useful up to date information such as briefly covering the serious effects of the 2017 Hurricane Maria on Dominica’s two endemic parrot species is also included. More generally there have been some improvements in the layout and organisation of the book such as better colour coding of the book’s sections making it easier to navigate. One thing to note in this new edition is that the book often purposefully breaks taxonomic order to group similar-looking families together for comparisons such as having swallows and martins straight after swifts in an otherwise non-passerine grouping. If the book were entirely full of unfamiliar taxa, this would probably bother me less and it does have some possible advantages in the field, especially for beginners. However, because I am familiar with many of the families (if not the species themselves!) and know roughly where to expect them normally, I find it a bit jarring and would probably prefer something closer to current taxonomic order as used in the first edition. Oddly, I also noticed that wrens randomly appear on the same page as some of the cuckoos, which really doesn’t make sense taxonomically or for comparisons. In terms of other minor criticises to make, there are still a few more bits of old artwork it would have been nice to update and it would also be helpful to illustrate some more of the distinct island subspecies. Although hardly unusual in a modern bird guide, it might have been good for encouraging local birding interest, to include some well recognised local species names in the accounts, such as for the endemic endangered Imperial Parrot/Amazon, which in Dominica is largely referred to by its native name the Sisserou. Also the map of the region covered near the start of the first edition, which I found quite useful to refer to, has unfortunately gone. However, these minor quibbles aside, this book represents a significant and much needed update on the previous edition and a fine, straightforward, easy to use bird guide in its own right and a strong contribution to furthering ornithology in the region. Although the larger Lynx Edicions guide is arguably a superior bird book in terms of content and has a slightly wider scope, at only around half the price and a significantly smaller, more portable size, the Helm Birds of the West Indies is both a more practical field guide and excellent value for money. Ideally, if you’re unfamiliar with the region’s birds you’d probably want both on a trip, perhaps with the Helm in your day bag and the Lynx back at base, but if space is at a premium, as it usually is when travelling, I can strongly recommend having this excellent guide along on its own on a birding trip to the West Indies.