About CES

Why do we need CES?

We need to monitor bird populations through time in order to conserve them effectively. Firstly, we need to know whether numbers are stable or changing, whether decreasing or increasing. If there is a change in numbers, particularly a decrease, we need to know why. Conservation action can then be targeted appropriately.

The key things that we need to monitor are numbers (abundance), the number of births (breeding success or productivity) and the number of deaths, usually recorded as the number that do not die (survival). Once we have this information, we can calculate expected changes in numbers and look for the stage of the life cycle which is most affected by environmental change. We can then find, or at least narrow down, the possible cause(s) of a decline. This is the philosophy behind the BTO Integrated Population Monitoring (IPM) programme. The CES scheme uses comparisons of the numbers of birds caught each year to provide indices of population change for 24 species. This information complements that from other BTO census schemes, such as the Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) and Common Birds Census (CBC), particularly for songbirds breeding in wetland and scrub habitats. Changes between years in the proportion of juveniles in catches are used as an index of productivity for the 24 species, complementing information from the Nest Record Scheme (NRS). Information on breeding success from CES is particularly valuable because it integrates success through the whole season (including the outcomes of multiple broods and early post-fledging mortality), whereas the NRS only monitors the results of single nesting attempts. Between-year recaptures of individual birds in the CES scheme are used to determine adult survival rates. This information complements that from general ringing from the BTO Ringing Scheme. For the species monitored by CES, higher quality information on adult survival per unit ringing effort is generated, compared with the low recovery rates from the general ringing.

What is CES?

The CES Scheme uses catches from standardised mist-netting to monitor key aspects of the demography of 24 common breeding songbirds. Around 130 sites are monitored through the breeding season, with twelve standard visits between May and August. Changes in the total number of adults caught provides a measure of changing population size, whilst the proportion of young birds caught forms an index of breeding success. Retraps of adult birds ringed in previous years are also used to estimate annual survival rates.

CE sites

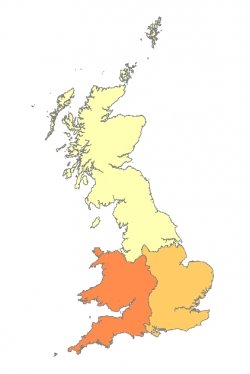

The popularity of CES ringing is increasing again after a drop-off during 2001 (due to Foot and Mouth restrictions). In 2014, 132 sites operated; fourteen of these operated for the first time. The majority of CE sites currently operated are in England (104 sites), but valuable contributions are received from Scotland (15 sites), Wales (9 sites) and Ireland (4 sites). The geographical spread of sites is impressive, but still somewhat biased towards the south and east due to the higher densities of ringers. Poor weather in the north and west can also make regular ringing more difficult.

The data collected through CES contribute to both national and regional trends. Currently, the number of CE sites only enables trends to be produced for the north, the east and the west (see map for regional boundaries). Unfortunately, there are not yet enough sites to produce country trends for Scotland, Wales or Ireland, or more specific regional trends; at least 20 sites are needed to produce a trend.

The majority of CE sites are in scrub (45 in dry scrub and 38 in wet scrub) and reedbeds (31) with a smaller number of sites in deciduous woodland (18). The sites are selected by the ringers themselves as those that are are suitable for catching satisfactory numbers of birds at each visit in habitats where successional changes can be managed. If the habitat were to change too dramatically, the results would be less meaningful because of changes in the chances of capturing individual birds.

Species monitored

The CES Scheme monitors 24 species of common passerines. Of these, two are on the 'Red list' of the Birds of Conservation Concern (BOCC) document (Song Thrush and Willow Tit) and four are Amber-listed (Dunnock, Willow Warbler, Bullfinch and Reed Bunting). The other species are Wren, Robin, Blackbird, Cetti's Warbler, Sedge Warbler, Reed Warbler, Whitethroat, Lesser Whitethroat, Garden Warbler, Blackcap, Chiffchaff, Long-tailed Tit, Blue Tit, Great Tit, Treecreeper, Chaffinch, Greenfinch and Goldfinch.

Adult numbers

A full analysis of changes in abundance measured by CES has been carried out for the years 1983-1995. Catches of most insectivorous resident species either increased or remained stable, while catches of resident thrushes, small finches, buntings and some trans-Saharan migrants declined. The largest increase in catches of adult birds were recorded for Robin, Wren, Greenfinch, Long-tailed Tit and Chaffinch, while the largest decreases in adult catches were recorded for Linnet, Redpoll, Spotted Flycatcher, Yellowhammer, Reed Bunting and Willow Warbler (Peach, W.J., Baillie, S.R. & Balmer, D.E. 1998. Long-term changes in the abundance of passerines in Britain and Ireland as measured by constant effort mist-netting. Bird Study 45, 257-275)

As an example, here we show the trends in the abundance of adults for Linnet, Long-tailed Tit and Wren.

Linnet

Adult numbers of Linnets on CE Sites show a very worrying decline, generally consistent with those shown by other BTO schemes; for example, the Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) shows that the breeding population has been declining since 1977. Linnet is already on the Birds of Conservation Concern Red List (being of high concern). Overall, Linnets numbers underwent a large decline between the mid-1970s and mid-1980s, probably due to a loss of weed seeds, but may have recovered since that time, perhaps due to the beneficial effects of set-aside. More recently, oil-seed rape has probably helped to compensate for losses of traditional foods. But CES catches of both adults and juveniles suggest that the decline of Linnets in scrubland continues, with productivity also in long-term decline. The number of Linnets caught on CE sites has now declined to the point where there is no longer sufficient data to analyse this species as part of CES.

Long-Tailed Tit

The population fluctuations shown by Long-tailed Tit are likely to be due to variation in winter weather conditions. The trend produced from the Breeding Bird Survey shows the effects of the very cold winters in the 1970s and early 1980s. CES information from 1983 onwards shows a period of recovery following a series of mild winters with the population increasing, though this has levelled off in recent years.

Wren

Like the Long-tailed Tit, winter weather is the major determinant of population changes in Wrens in Britain. Even a short spell of winter weather, severe enough to prevent efficient feeding, results in high mortality. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, catches of adult Wrens have fluctuated markedly, suggesting recoveries from cold winters until reduction again in the next hard spell.

Breeding success

We are also able to produce an index of productivity (a measure of breeding success) from CES data. Information on individual nesting attempts from the Nest Record Scheme allows a detailed investigation of success at various stages of the breeding cycle for many species, but cannot provide information on the number of breeding attempts (and 'whole season' productivity). Productivity measured by CES integrates success (or failure) across the whole breeding cycle, including all breeding attempts and early post-fledging mortality. We currently produce trends in productivity for all CES species using generalised linear modelling methods. These will allow influences of short-term weather variation on productivity to be controlled, so that true long-term trends are revealed.

Survival

The Sedge Warbler is a common breeding species throughout most of Europe, wintering south of the Sahara Desert in West Africa (see Migration Atlas). In Britain, numbers of Sedge Warblers breeding in farmland and riparian habitats fluctuate markedly from year to year but declined by about two-thirds between the mid-1960s and mid 1980s. Survival rates of adult Sedge Warblers were estimated for the period 1969-1984 using mark-recapture data collected at two long-running CE Sites in southern England (Marsworth Reservoir, Hertfordshire and Wicken Fen, Cambridgeshire) (Peach, W.J., Baillie, S.R. & Underhill, L. 1991. Survival of British Sedge Warblers Acrocephalus schoenobaenus in relation to west African rainfall. Ibis 133:300-305).

The results of the investigation showed that fluctuations in the population levels and annual adult survival rates of British Sedge Warblers since the late 1960s are strongly correlated with indices of wet season rainfall in the West African winter quarters, the higher the rainfall in West Africa the greater the adult survival rate (graph). This suggests that the continued expansion of the Sahara Desert due to droughts, land drainage and over-grazing is a threat to our Sedge Warblers, as well as to populations of many trans-Saharan migrants.

Share this page