Scotland’s winter visitors: why and how do they migrate?

Relates to projects

Now that the clocks have changed and ‘the nights are fair drawin’ in’, you’ve likely noticed a shift in the birds around us. Gone are the Swallows and singing warblers (well, mostly, but more on that later), replaced with skies full of geese and vast numbers of waders visiting our shores. But how and why do these birds arrive?

For migrant birds, there are both ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors that drive their migration. Typically, it’s a mix of factors. Different species also migrate at different times, and in different ways - in flocks, in family groups or alone. From geese and swans to thrushes and warblers, discover the secrets of our winter birds' migration.

Birds like swans, geese, and waders are largely dependent on open water, fresh vegetation and soft mud or sand to feed in. They have no choice but to abandon their Arctic breeding grounds before their food sources freeze over - a pretty clear ‘push’ factor! When the birds arrive in our milder climate, they find huge estuaries and inland water bodies that rarely, if ever, freeze and are brimming with energy-rich food.

Migration strategies vary hugely between these species. Whooper Swans migrate as family groups, making the flight from Iceland in a non-stop ocean crossing to the UK. The parents remain with the young birds throughout the winter, finding rich sources of food and helping defend the young against predators. Next time you see a Whooper Swan, look for the lighter grey young alongside the bright white parent birds.

Compare this high level of parental care with that of the Purple Sandpiper - a diminutive wader that visits our rocky shorelines in winter.

Purple Sandpipers breed in the high Arctic and, remarkably, the female leaves the breeding grounds almost as soon as the eggs have hatched. Like many other wader species, their young are ‘precocial’, which means they are relatively independent of their parents after hatching and require little care. The adult male stays with the young birds, though, often until they fledge (learn to fly).

This early departure by female waders helps explain why we can observe wader migration as early as July, a time when many species are still busy with the breeding season. As well as female birds leading the vanguard, these early arrivals are probably also failed breeders which have no chicks to care for. The males and fledged young follow in later weeks.

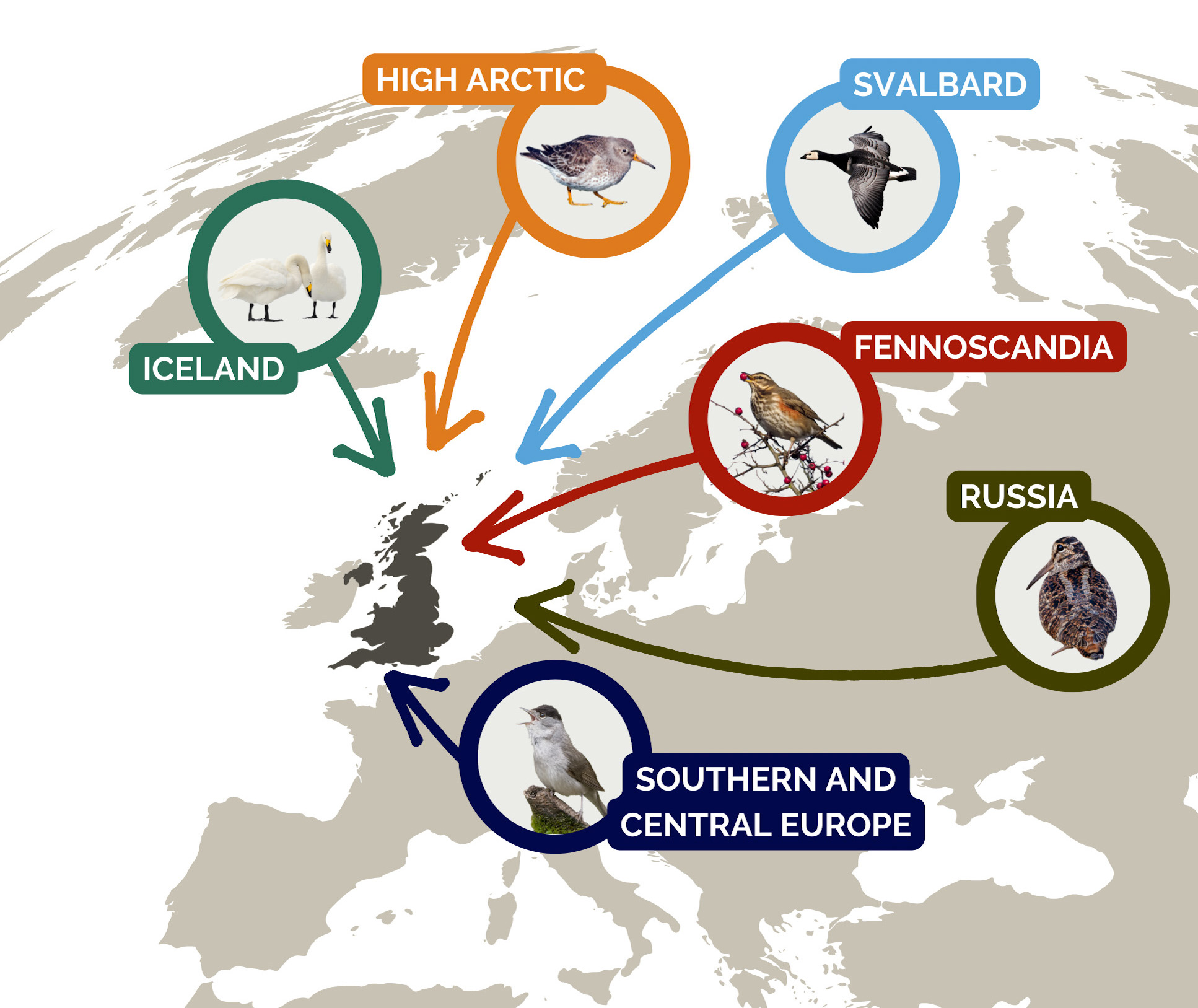

Where do our winter visitors migrate from?

Many species' migratory journeys converge in the UK during our winter months.

Some species escape from the freezing conditions in their arctic breeding grounds to the UK's warmer climate, such as Whooper Swan (Iceland), Barnacle Goose (Svalbard; birds also arrive from a population in Iceland), and Purple Sandpiper (high Arctic).

Its situation in the Gulf Stream also makes the UK warmer than equivalent latitudes on the continent. This makes it a winter destination for birds breeding in Russia, like Woodcock, and even in southern and central Europe, like Blackcap.

Numbers of other species in the UK are partially dependent on food availability elsewhere. Poor berry crops in Fennoscandia, for example, push species such as Redwing across to the UK in search of food.

The biggest ‘pull’ factor for migrant birds is an abundant food supply.

In some years, for example, a poor berry crop in Scandinavia drives huge ‘irruptions’ of Waxwing into nearby countries where berries are more numerous. Many arrive in the UK, where they gorge themselves on native berries like Rowan and Holly, and on the fruits and hips of ornamental plants in our parks and gardens. Berry trees are often planted in supermarket car parks, which makes them an excellent place to look out for this garrulous species.

Also taking advantage of the crop of berries are migrant thrushes. Blackbirds, Song Thrushes, and Mistle Thrushes from continental Europe make their winter home here and join our resident birds.

Fieldfares from northern Europe and Redwings from Fennoscandia and Iceland are also drawn to the UK but can be shy and wary - get to know their calls and you’ll have a better chance of finding them!

The sounds of winter

These birds are all visit the UK in winter, and are partial to a feast of berries, hips and haws. Learning their calls can help you locate and identify them.

Not all the migration is simply north to south, though. In early winter, there is a mass movement of Woodcock towards the UK, as birds escape the approaching winter in northern and eastern Europe and Russia. Their arrival on our shores is so consistent that this month's full moon is often known as the 'Woodcock moon'.

Much of the Woodcock's winter migration is east to west, as birds move across to our milder, sheltered woodlands where they spend the winter probing the soil for worms and other invertebrates. This pattern was revealed in part through ringing studies.

Ringing has also revealed a fascinating insight into the lives of our Blackcap - a fairly common and widespread warbler that does indeed sport a nice black cap (well, the males do. In females, it’s brown).

Garden BirdWatch

Do you see Blackcaps in your garden in winter? Join our Garden BirdWatch community and help us research garden wildlife.

We typically see and hear Blackcaps in our woods and gardens from spring through to late summer, but since the 1970s, more and more people have noticed Blackcaps spending the winter in and around gardens, taking advantage of foods put out for garden birds. The number of wintering Blackcaps rose and rose, and now as many as 13% of Garden BirdWatch gardens report Blackcap during the colder months.

Initially, the assumption was that these records reflected a change in the behaviour of the Blackcaps which visited us in summer; maybe the warmer climate meant they didn't feel the drive to fly south, particularly as they could also take advantage of garden bird feeding. However, ringing studies revealed a much more elaborate explanation for this new behaviour.

As far back as the 1950s, Blackcap in Germany and Austria had changed their migration habits. Instead of going southwest to Spain, they started travelling north and west and arriving in Britain! Meanwhile, British-breeding birds departed for the continent. From our perspective as birdwatchers, this change was imperceptible - just as ‘our’ Blackcap left the UK, they were replaced with birds from Europe. Data from ringing schemes has supported other research about this species’ migration, and helped us to discern this hitherto unknown aspect of these birds’ lives.

The Chiffchaff is another warbler that is being recorded year-round more and more frequently. Are these birds the ones that breed with us in summer and give their lovely “chiff-chaff-chaff-chiff” song, or are they - like the Blackcap - winter visitors from Europe?

We’re spoilt for choice in the UK, with lots of amazing coastal and freshwater wetlands that are packed with birds in winter. Find your nearest estuary or reserve and make sure to give it a visit!

If you’re in Scotland, the Scottish Ornithologists' Club Where to Watch Birds in Scotland app will help you narrow the search by site or by species.

As the birds around us go about their daily lives, it’s remarkable to think about what they go through as individuals.

How can something as tiny as a Goldcrest, which weighs only 6 g, cross the North Sea? Why do some Lesser Black-backed Gulls only migrate a short distance from their breeding grounds, when others go all the way to West Africa? How do young waders, abandoned by their parents in the high Arctic, know how to navigate safely to their wintering grounds?

Bird migration is a fascinating topic, and certainly, one that invites more and more questions the deeper you delve.

Support the future of our birds

Our surveys and monitoring schemes are vital. The data they produce help us drive positive change for the UK’s birds.

But increased pressure on funding is putting our surveys and data at risk – which is why we need your support.

Donate today

Share this page