A Word with Tim Birkhead

Ornithologist and author of Birds and Us: A 12,000 Year History, from Cave Art to Conservation

Jasmine Canham

Jasmine is a BTO Youth Rep and is currently studying Wildlife Conservation at Bangor University. She loves hands-on conservation work, birdwatching and helping with toad patrols, and hopes to inspire other young people to get out in nature.

Relates to projects

Tim Birkhead is a well renowned British ornithologist, researcher, author and Vice President of the BTO, known for his rich research history looking at sperm competition and promiscuity in birds. He has written several popular science books, covering topics ranging from bird eggs to the history of ornithology.

I recently had the pleasure of sitting down (virtually) with Tim to talk about his new book, Birds and Us: A 12,000 Year History, from Cave Art to Conservation. Tim has an incredible wealth of knowledge of all things ornithological, I really enjoyed chatting with him and I’m excited to share with you some extracts from our interview.

Birds and Us: A 12,000 Year History, from Cave Art to Conservation

is available to buy from NHBS.

What inspired the idea for Birds and Us?

“Lockdown!” Tim answered.

Having recently retired from teaching at Sheffield University, he missed the busy day-to-day existence and socialising with colleagues. Birds & Us became a perfect escape from the pandemic, and the project gave a certain focus to the lockdown existence.

A book along these lines had been in the pipeline for a few years as Tim found himself becoming increasingly interested in history. “I hated history at school”, he told me, “probably because it was so badly taught! But having a focus - in this case, birds - made history come alive for me”.

One book he encountered was ‘The Folklore of Birds’ written by E.A. Armstrong, a collection of different folk beliefs about birds such as the well-known magpie rhyme one for sorrow, two for joy…

But as a scientist, he is interested in how we’ve come to acquire our knowledge of birds. “I found Armstrong’s collection very unsatisfying at some level,” he said, “as I wanted a proper explanation of why the folklore developed!” So, combining a scientific and cultural perspective, he decided to adopt a more historical approach, looking at relationships between birds and people over time.

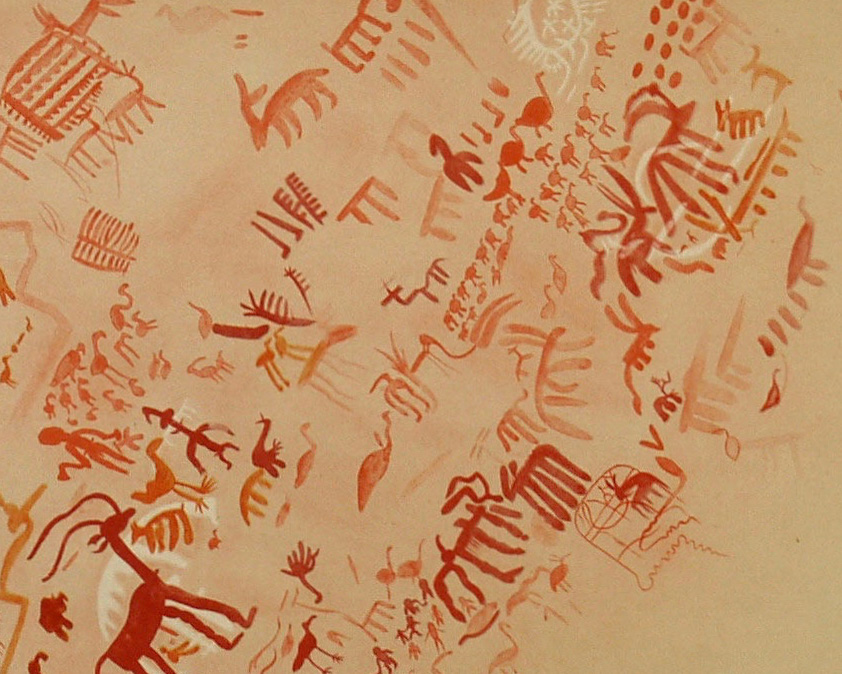

The biggest inspiration for the book came about in 2018 when Tim was visiting Spain. Although he had stayed in Andalucia many times over the years, it was only on this most recent trip that he learnt of El Tajo de las Figuras, a tiny cave with walls covered in hundreds of spectacular paintings of birds, left behind from the Neolithic era.

“As soon as I saw it, I knew it would be the perfect opening chapter for the book, but also the framework for how I thought about our relationships with birds,” Tim told me.

What Tim found particularly striking about the paintings was that these paintings seemed to capture the birds’ living essence. Unlike more recent portrayals, like the dead game birds in still life of the 17th and 18th centuries, these cave paintings reflect just how the Neolithic people would have seen the birds whilst gazing out over the vast wetlands.

“They were represented with uncanny yet simplistic beauty,” Tim reflected. “These paintings definitely set the stage for looking at how our views of birds have changed over time.”

Timeless beauty

Art is a very prevalent theme throughout the book, from the mysteries of El Tajo cave to the works of artists like J.J. Audobon. I ask Tim why he thinks it is so universal to express birds through art.

“In many ways, birds are so much more evident than other wildlife,” he says. “They are abundant, visible and have such diverse structure and colour”.

“They are good to eat in many cases too,” he continued with a laugh, “although that’s not so popular as a notion today!”

I can’t imagine many BTO members wanting to snack on any of our charismatic native species, but it certainly raises the point on how reliant we once were on these animals.

As to why people felt compelled to paint them, Tim believes the answer has varied over time. “When I was in the cave with Dr María Lazarich [archaeologist], I asked her about the functions of the art. I said to her - and this reflects my career as a university teacher - it smacks of a tutorial!”.

His interpretation was that the paintings functioned almost like an instruction manual, the original ID guide; though the paintings were simple, one can still distinguish the different species. “They were painted as they were seen and behaving, because this was key to identifying - and identifying with - the birds”.

But Tim believes the continued presence of birds in art is more simple than that. “People were inspired by birds, and painted birds, because they are beautiful”.

The music of birds

But birds aren't only beautiful to look at. Does Tim have a favourite birdsong, I wonder?

“I’m going to say Bullfinch,” he replied, after considering it for a minute.

“In the wild, they have the most pathetic, simple song you’ve ever heard” he laughed, but went on to explain their redeeming feature: the ability of hand-reared young to learn and mimic tunes from their trainers.

“The males could repeat the tunes as the trainer whistled them, and infinitely better!” Tim told me. Tim witnessed this in a video by Jürgen Nicolai, who in the 1960s and 70s was a PhD student investigating the relationship between bullfinches and their trainers. “Jürgen’s Bullfinch burst into song every time he walked into the room. It was heart-rending: the Bullfinch seemed completely in love with him, and he with the Bullfinch”.

Tim explained how Bullfinches are very monogamous birds, and there is evidence that suggests this requires more cognitive ability than promiscuity for better awareness of, and communication with, a partner. In captivity, the trainer takes the place of its mate, and so by repeating the song the young Bullfinch is reinforcing the bond with its human owner.

Ornithological pioneers

There are plenty of historical figures and research discoveries that Tim discusses in ‘Birds & Us’, but Tim feels that two men - Frances Willughby and John Ray - deserve a special mention, for pioneering the scientific approach to birds and influencing the future of ornithology.

Tim initially focused on John Ray, the more well-known of the two. However, he realised through meeting with Willughby’s descendants - and hearing their declaration that “Willughby was the genius!”, that it was, in fact, Willughby he should be researching.

“It was one of the most exciting and most productive ventures of my life,” Tim said. “Willughby’s book on birds, published in 1676, was a model for all subsequent ornithological encyclopedias”. The fruit of this research was another of Tim’s excellent popular science books - ‘The Wonderful Mr Willoughby: The First True Ornithologist’.

Our future with birds

Tim hopes that his book will draw attention to our changing attitudes towards birds over time, and encourage us not to take how we feel about them today for granted.

“For most of human history, birds have been seen as a resource - they’ve been eaten, hunted, used to stuff pillows, and studied in destructive ways such as shooting and egg collecting”.

“Today, we are acutely sensitive to threats to birds and the severe declines populations are facing. We shouldn’t take it for granted that what we feel about birds today, wanting to protect them, is what people will feel in the future."

Above all, it is about encouraging people to care about birds. “Making people care now - and raising awareness that our attitudes can change – will, I hope, instil care in future generations.”

“By making birds more interesting and more accessible, I hope I might be successful.”

BTO research informs conservation of birds across the globe.

If our future with birds is important to you, please consider a donation.

Find out how you can help

Share this page