Why ring birds?

As discussed on the History of ringing page, birds have been ringed in Britain & Ireland since 1909. Today, nearly 3,000 registered volunteers invest their time and money ringing a million birds in Britain & Ireland each year - but why? Given the rapid advances in tracking technology witnessed over recent decades, is traditional ringing still necessary?

A matter of life and death

in the Netherlands. Photograph by John Harding.

When the BTO Ringing Scheme was established over 100 years ago, the primary focus was the study of bird movements. While ringing data can still be used to study migration and dispersal, today they are primarily used in the study of population change. ‘Population modelling’ may sound like a complex process, but the basic principle is relatively straightforward – bird numbers are determined by the number of fledglings produced and the subsequent survival of both those youngsters and their parents.

Nest Record Scheme participants collect data on productivity and ringers collect data on survival, allowing the relative influence of each on population trends, generated by thousands of volunteers taking part in the BTO/JNCC/RSPB Breeding Bird Survey and other similar schemes, to be assessed. This is essential information for conservationists attempting to reverse declines - if numbers are dropping due to starvation over winter, targeting agri-environment funding at improving nesting habitat is unlikely to yield the desired results.

So how can ringing birds provide data on survival? Each BTO metal ring bears a unique number, enabling individuals to be identified on subsequent encounter. Until recently, survival rate calculations were based on numbers of dead birds reported by members of the public, which works well for larger species that tend to meet their end in obvious places, such as Blackbirds and Barn Owls; but when was the last time you saw a dead Willow Warbler? However, advances in statistical techniques have allowed survival to be calculated from recaptures of previously ringed birds, so the question shifts from ‘How many birds do we know have died?’ to ‘How many do we know are still alive?’.

And so we meet again

These ‘recapture models’ have many advantages, but the results are influenced by the likelihood of encountering those individuals that have survived, so it’s important to either standardise ringing effort, as is done at Constant Effort Sites (CES), or record it so that it can be accounted for subsequently, as happens during Retrapping Adults for Survival (RAS) studies. It’s also vital to target birds when they’re most sedentary so we can be confident that any missing individuals haven’t simply moved to another site. Luckily, most adult birds remain faithful to the breeding site they select in their first year; monitoring juvenile survival presents a bigger challenge as many will disperse away from the area in which they were raised before attempting to rear their own offspring.

A splash of colour

and tend to frequent bare habitats, giving birders good viiews of their legs.

Photograph by Ruth Walker

Recent decades have witnessed a marked increase in the use of colour rings, flags and tags which allow individuals to be identified in the field. Colour-marking is particularly useful for species that can be ringed as nestlings, but which are challenging to catch as adults, including many raptors and seabirds, and for birds such as House Sparrow that are often simply too wily to be caught more than once.

A fantastic bonus is that it allows those without a permit to contribute to ringing projects by resighting marked birds. In the future, we may not even need to see the birds at all - Passive Integrated Transponder (PIT) tags, similar to the chips vets place in cats and dogs, can be fitted to rings and allow a birds’ presence to be detected automatically by a receiver; this is ideal for species that return to predictable locations, such as nest boxes or feeders.

As with all monitoring, the collection of ringing data is an ongoing process producing annual results; these results tell us what is happening now, how the current situation compares to the past and what the future may hold. This is why it is important to cover the common species as well as those that are already known to be in decline. In addition, the vast datasets we can collect on birds such as Blue Tit allow us to look at responses to pressures such as climatic warming in minute detail, which may ultimately benefit scarcer species like Willow Tit.

Next generation ringing

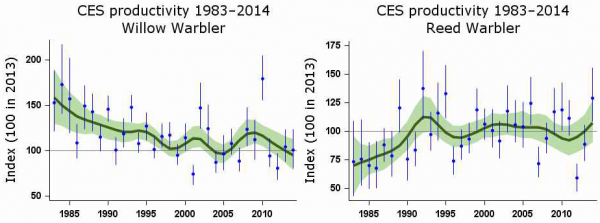

Survival data isn’t the only output generated by ringing; the information collected can also tell us about breeding success (productivity), dispersal, phenology and the condition of birds. The ratio of captured youngsters to adults gives an indication of annual breeding success, a measure influenced by i) the average number of nesting attempts initiated per pair, ii) the average number of young fledged from each attempt, and iii) the survival rate of those juveniles after they leave the nest.

Collecting data on the age of birds during ringing therefore allows productivity to be estimated alongside survival; by simultaneously monitoring the two main processes that determine whether a species is in decline, the chances of identifying, and ultimately tackling, the cause are greatly increased. The use of age ratios at capture to assess breeding success can be particularly informative where direct data collection via nest monitoring is not feasible due to the inaccessibility of breeding grounds, as is the case for many of our wintering wildfowl and waders.

over time while that of the Reed Warbler, a species currently expanding its range, has increased.

Timing is everything

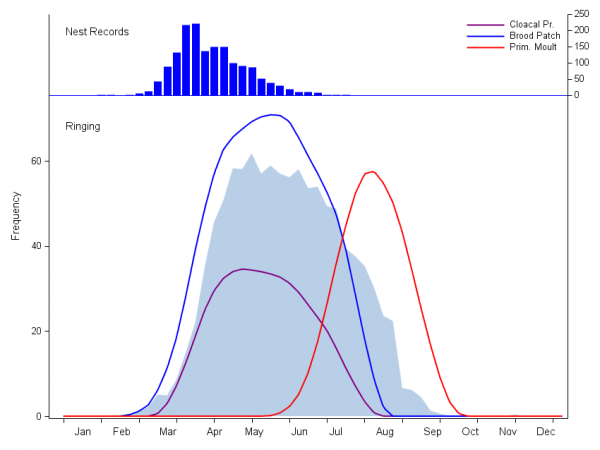

Several recent analyses suggest that those migrant songbirds which fail to advance their nesting dates in response to a warming climate are at greatest risk of decline, possibly due to growing asynchrony between offspring demand and invertebrate prey availability, a process termed phenological disjunction. The timing of egg laying has traditionally been monitored by the Nest Record Scheme, but related features displayed by parent birds (brood patch formation, moult) and recorded by ringers have the potential to impart similar information. Migrants may be particularly susceptible to temporal mismatch with prey if their ability to advance breeding is constrained by arrival dates and the data collected by ringers at Bird Observatories play a key role in determining the numbers of birds entering/leaving the country on any given date.

ringers can identify annual changes in the timing of breeding for species such as Blackbird.

Moving on

The capacity for traditional bird ringing to identify migration routes and destinations can be limited by observer effort away from the breeding grounds, as illustrated by the rapid expansion in our knowledge of sub-Saharan migrant ecology already achieved by tagging, a technology still in its relative infancy. However, on other flyways results can be extremely impressive. The Migration Mapping Tool uses European ringing data for selected wildfowl, waders and gulls to chart the typical passage of birds between countries throughout the year and has proven highly valuable when identifying potential Avian Influenza hotspots during outbreaks.

These long journeys may be impressive, but short-distance dispersal is equally important, determining a species’ capacity to colonise new sites. Adults tend to be relatively faithful to breeding locations but juveniles may move long distances between hatching and nesting. As these movements are unpredictable and variable, study of dispersal requires large numbers of young birds to be marked and a national network of recapture sites to be established, which provides a pretty good definition of the BTO’s Ringing Scheme!

Find out more

Survival trends are generated annually from both CES and RAS data. All CES and selected RAS trends are published in the online BirdTrends report and more RAS trends can be found on the RAS results webpages. A preliminary analysis of the CES data for each breeding season is published on the CES results webpages in November of the same year.

A recent study by Rob Robinson et al. (2014) used the broader Ringing Scheme dataset to construct population models for 17 species using novel statistical techniques. One interesting conclusion was that population declines tend to be driven by a fall in recruitment of young birds, while increases typically result from improved adult survival.

Further information on the how bird ringing contributes to science and conservation is available in the EURING Bird Ringing for Science and Conservation guide.

Reference

Robinson, R. A., Morrison, C. A., Baillie, S. R. (2014), Integrating demographic data: towards a framework for monitoring wildlife populations at large spatial scales. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 5: 1361–1372.

Share this page