Ring Ouzel

Turdus torquatus (Linnaeus, 1758)

RZ

RINOU

RINOU  11860

11860

Family: Passeriformes > Turdidae

This striking Thrush, a little larger than a Blackbird, is a bird of our uplands, breeding from Dartmoor to the Scottish mountains.

The white bib of the male and creamy bib of the female combined with a silvery wing panel set this thrush apart from all others. It is also the only thrush that visits Britain & Ireland just for the summer months, arriving in mid-March and departing during September and October, spending the winter as far south as North Africa. In recent years a handful of birds have been found in the UK during the winter, mostly in gardens.

Ring Ouzel has been on the UK Red List since 2002 due to long-term declines in breeding population and range.

Exploring the trends for Ring Ouzel

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Ring Ouzel population is changing.

trends explorerIdentification

Ring Ouzel identification is sometimes difficult. The following article may help when identifying Ring Ouzel.

Identifying Ring Ouzel and Blackbird

With Ring Ouzel migration about to reach its peak this wonderful thrush can turn up almost anywhere. Check out the latest identification video to help separate this species from Blackbird, both on the ground, in flight and by song.

SONGS AND CALLS

Listen to example recordings of the main vocalisations of Ring Ouzel, provided by xeno-canto contributors.

Flight call

Alarm call

Song

Develop your bird ID skills with our training courses

Our interactive online courses are a great way to develop your bird identification skills, whether you're new to the hobby or a competent birder looking to hone your abilities.

Browse training coursesStatus and Trends

Population size and trends and patterns of distribution based on BTO surveys and atlases with data collected by BTO volunteers.

CONSERVATION STATUS

This species can be found on the following statutory and conservation listings and schedules.

POPULATION CHANGE

This species has been monitored by single species surveys: a 58% population decline was estimated for the period between 1988-91 and 1999, warranting red listing (Gregory et al. 2002). Further fieldwork in 2012 found 5,332 territories (4,096-6,875), using the same methods as in 1999; This equated to a (non-significant) decline of 29% since 1999 (Wotton et al. 2016). The 2012 study also used playback to measure the efficiency of the national survey methods and estimated that 84% of territories were located in 2012, giving a revised population estimate of 6,348 territories (4,825-8,198). Along with the population decline, the range of Ring Ouzel has also contracted: By 2008-11, the number of occupied 10-km squares had fallen by 43% since 1968-72 (Balmer et al. 2013).

Numbers across Europe have been broadly stable since 1998 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

Exploring the trends for Ring Ouzel

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Ring Ouzel population is changing.

trends explorerDISTRIBUTION

As a breeding species the Ring Ouzel is a bird of the uplands, having a mostly northern and western distribution. It is a very localised breeder in Ireland.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

| No. occupied in breeding season | 428 |

| % occupied in breeding season | 14 |

| No. occupied in winter | 159 |

| % occupied in winter | 5.3 |

European Distribution Map

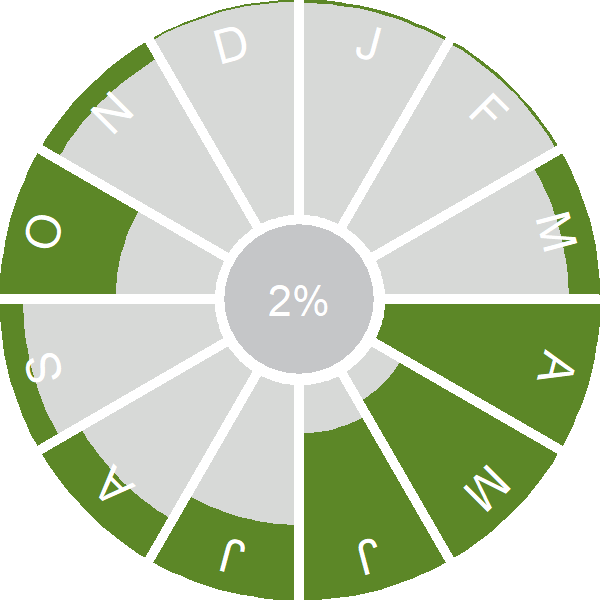

DISTRIBUTION CHANGE

The Ring Ouzel breeding range has contracted by 43% in Britain and by 57% in Ireland since the 1968–72 Breeding Atlas. Recent losses mean Ring Ouzels no longer breed in Exmoor and they are now largely absent from most of central Wales, the western half of the Scottish Southern Uplands and Co. Wicklow. In Scotland north of the Central Belt, Ring Ouzels have contracted from the range margins, particularly in the southwest and far north. Intensive studies confirm many breeding populations throughout Britain are in decline.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

| % change in range in breeding season (1968–72 to 2008–11) | -42.9% |

| % change in range in winter (1981–84 to 2007–11) | +300% |

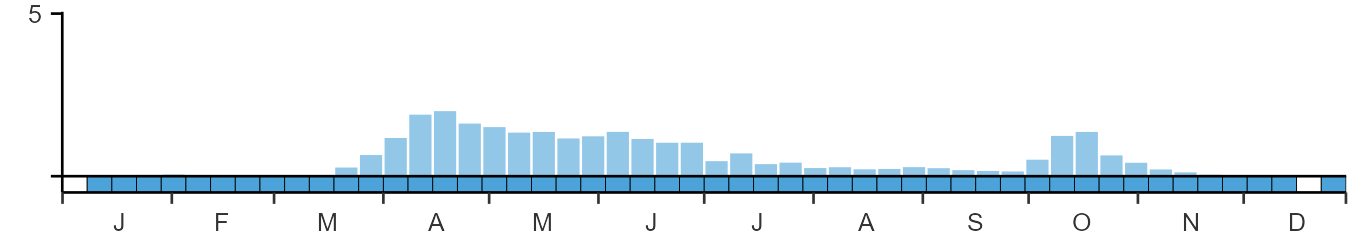

SEASONALITY

Ring Ouzel is a summer visitor and passage migrant, arriving from mid March onwards; there is a pronounced passage of continental birds in October.

Movement

Information about movement and migration based on online bird portals (e.g. BirdTrack), Ringing schemes and tracking studies.

An overview of year-round movements for the whole of Europe can be seen on the EuroBirdPortal viewer.

RINGING RECOVERIES

View a summary of recoveries in the Online Ringing Report.

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Biology

Lifecycle and body size information about Ring Ouzel, including statistics on nesting, eggs and lifespan based on BTO ringing and nest recording data.

PRODUCTIVITY & NESTING

Exploring the trends for Ring Ouzel

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Ring Ouzel population is changing.

trends explorerSURVIVAL & LONGEVITY

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report

Exploring the trends for Ring Ouzel

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Ring Ouzel population is changing.

trends explorerBIOMETRICS

Wing Length

|

Adults | 143.5±3.6 | Range 138–150mm, N=139 |

| Juveniles | 142.9±3.7 | Range 137-148mm, N=163 | |

| Males | 145.3±3.1 | Range 140–151mm, N=75 | |

| Females | 141.2±2.8 | Range 136–146mm, N=62 |

Body Weight

|

Adults | 106±11.59 | Range 91.0–128g, N=127 |

| Juveniles | 104±9.84 | Range 89.0–123g, N=148 | |

| Males | 107±12.26 | Range 90.0–129g, N=66 | |

| Females | 105±10.71 | Range 91.0–126g, N=59 |

Feather measurements and photos on featherbase

CODES & CLASSIFICATION

Ring size

|

C |

Field Codes

|

2-letter: RZ | 5-letter code: RINOU | Euring: 11860 |

For information in another language (where available) click on a linked name

Research

Interpretation and scientific publications about Ring Ouzel from BTO scientists.

CAUSES AND SOLUTIONS

Causes of change

There is little evidence explaining either the demographic or ecological drivers of the decline in this species, although low survival between breeding seasons has been identified as a major cause of national decline.

Further information on causes of change

Long-term surveys coordinated by the Ring Ouzel Study Group confirm that declines have occurred throughout the British range (Sim et al. 2010).

British & Irish bird observatory data show a decline in spring passage Ring Ouzels at western locations during 1970-98 that matches the estimated UK breeding decline, but no decline at eastern observatories where most birds are of Fennoscandian origin (Burfield & Brooke 2005). These authors infer that, since these populations winter together, the reasons for decline among UK breeders must lie on the breeding grounds or on passage: they also point out that UK birds are more exposed to hunting pressures, particularly in southwest France.

It has proved difficult to establish any reasons for decline that are linked to the breeding grounds (Buchanan et al. 2003). In southeast Scotland, however, the breeding sites that are still occupied tend to be those at higher altitude and that have retained extensive cover of heather (Sim et al. 2007b). In the same study, it was shown that declines were greatest in years following warm summers on the breeding grounds and also greater two years after high spring rainfall in Morocco: these results suggest that the population decline could be linked to reduced food supplies, and consequently higher rates of natural mortality, in autumn and winter (Beale et al. 2006). Large areas of apparently suitable juniper scrub, with abundant berries but no wintering Ring Ouzels, exist in the Atlas Mountains, however (Green et al. 2012).

Low survival between breeding seasons is apparently a major national cause of decline (Sim et al. 2010). Within Glen Clunie, however, Sim et al. (2011) found that varying combinations of demographic factors produced each year-to-year decline, with reduced early-season productivity, rates of re-nesting and first-year survival all playing a part. A two-year experimental study found that the provision of supplementary food during the breeding season did not have an effect on reproductive success or post-fledging survival suggesting that invertebrate food availability was not a problem at this site, although the authors caution that the study area has intensive predator control so the results may only be directly relevant in similar areas (Sim et al. 2015).

Information about conservation actions

The main cause of the decline may be related to low survival between breeding seasons, and the research has not identified any clear causes of decline that are linked to the breeding grounds. Therefore, the options for taking immediate conservation action to benefit Ring Ouzels in Britain appear limited.

However, low post-fledging survival is one of the possible causes of decline which could occur on the breeding grounds. Variation in chick condition was smaller in territories with better habitat (greater grass and sedge cover and less bracken) (Davies et al. 2014); hence increased grass cover may help ensure a greater proportion of chicks are in good condition to survive immediately after fledging. Juveniles forage on invertebrates in grassland during June to mid-July, but then switch to feed mostly on berries on heather moorland until early September, so a wider variety of habitats may be needed later in the summer to support fledged young prior to migration (Sim 2012).

Links to more information from ConservationEvidence.com

Would you like to search for another species?

Share this page